If intelligent life beyond Earth (should it exist) could view our planet right now, they might be astonished by the great plume of smoke curling over the ocean.

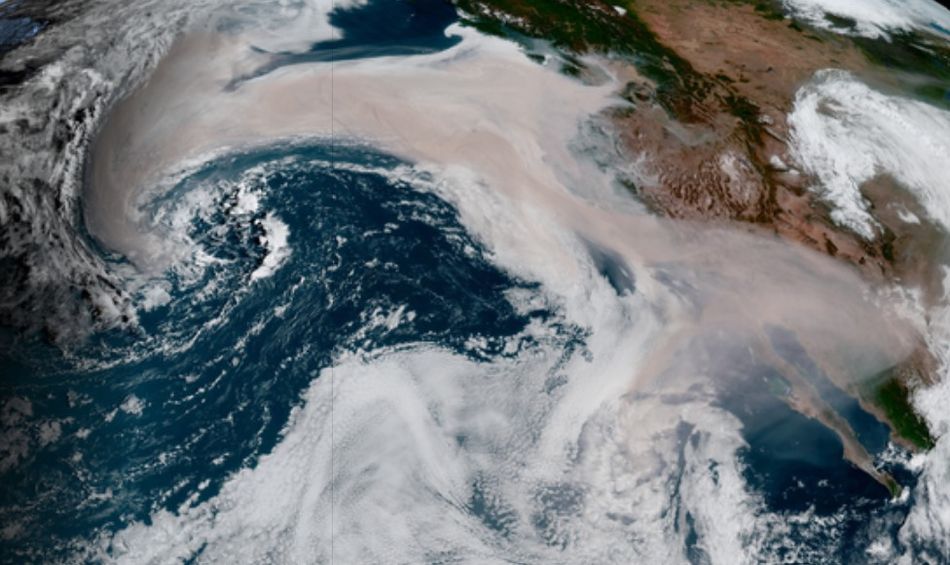

It’s a wild sight, captured by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) GOES-West satellite. Potent winds have blown smoke from the historic Western wildfires over 1,000 miles from the coast, into the northern Pacific Ocean. The plume has traveled east too, reaching Mexico. (Hazy skies, from earlier fires, have also been spotted over Europe.)

Record-breaking heat waves, profound record to near-record dryness, and strong winds have allowed massive wildfires to rapidly spread in California, Oregon, and Washington. What’s more, millions of dead trees (killed by climate-enhanced drought and bark beetles) along with mismanaged, overcrowded forests have further amplified these blazes.

The resulting smoke has punished Western regions, and in some places turned the daylight into an eerie, dark orange glow. Winds are now blowing bounties of profoundly thick smoke over the Pacific Ocean.

“Running out of adjectives to describe #smoke emitted from Western US wildfires,” tweeted NOAA’s National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service Center for Satellite Applications and Research aerosol team, which tracks smoke over the region.

Out over the open ocean, the smoke is now wrapping around a cyclone (a general term for a zone in the atmosphere where winds rotate around an area of low pressure).

The smoke plume over the Pacific Ocean on Sept. 11, 2020.

Image: noaa / cira

You can see the smoke from the West Coast wildfires in this photo taken by the DSCOVR spacecraft nearly 1 million miles from Earth. https://t.co/6VSivmvo1L

— Miriam Kramer (@mirikramer) September 11, 2020

Smoke from massive fires can travel around the globe in about a week. But the largest component of wildfire smoke is invisible. Carbon dioxide (CO2) makes up some 90 percent of wildfire smoke. It lives there for hundreds of years. Critically, CO2 is a potent heat-trapping gas, so while in the atmosphere the newly released gases are contributing to the relentlessly warming climate.

A warmer climate means drier trees, shrubs, and grasses, meaning the vegetation burns much more easily.

“When we talk about how climate enables fire activity, we’re often talking about how dry fuels are,” John Abatzoglou, a fire scientist at the University of California, Merced, told Mashable as some of the largest fires in California history burned in late August. “This year is embedded within a long-term uphill climb toward warmer, drier, and smokier climates.”

Wildfires are not inherently bad. There is good fire. Fires naturally thin overcrowded forests (which decrease the likelihood of future infernos) and maintain healthy ecosystems. For this reason, California and the U.S. Forest Service just committed to thin millions of acres of mismanaged forest.

But still, modern fires are burning in a hotter climate.

Carbon emissions from California blazes are already the highest they’ve been in the 18-year wildfire satellite record. Five of the largest 20 fires in Golden State history have burned in 2020, so far.

WATCH: Where does smoke go to die in the atmosphere?