Did you know we have an online conference about product design coming up? SPRINT will cover how designers and product owners can stay ahead of the curve in these unprecedented times.

Hello, Bonjour, Hola, 你好, Guten Tag, こんにちは, Привет, Merhaba, Jó Napot, Здраво!

Designers at global companies frequently work with geographically distributed teams. We also regularly work on digital products designed for global consumption for clients located all over the world. Yet designers, forgetting there’s a wider world out there, continue to live in a bubble and tend to focus only on their local culture, traditions, and language.

Cross-cultural design indisputably presents complex challenges—both linguistic and cultural. Nevertheless, most designers wrongly assume that designing products for different cultures simply requires language translation (localization), switching currencies, and updating a few images to represent the local culture. The road to successful cross-cultural design with great UX is far more complicated and rife with pitfalls.

Who can forget the seminal cautionary tale of why Chevrolet’s “Nova” failed in Latin America? The story claims the branding failed because the name “Nova” means “no go” in Spanish. This tale of substandard branding has been recounted to generations of business students as an object lesson in the failure to do reliable, in-depth cross-cultural research. There’s only one problem with the story: It’s not true.

[Read: A designer’s guide to creating effective dashboards]

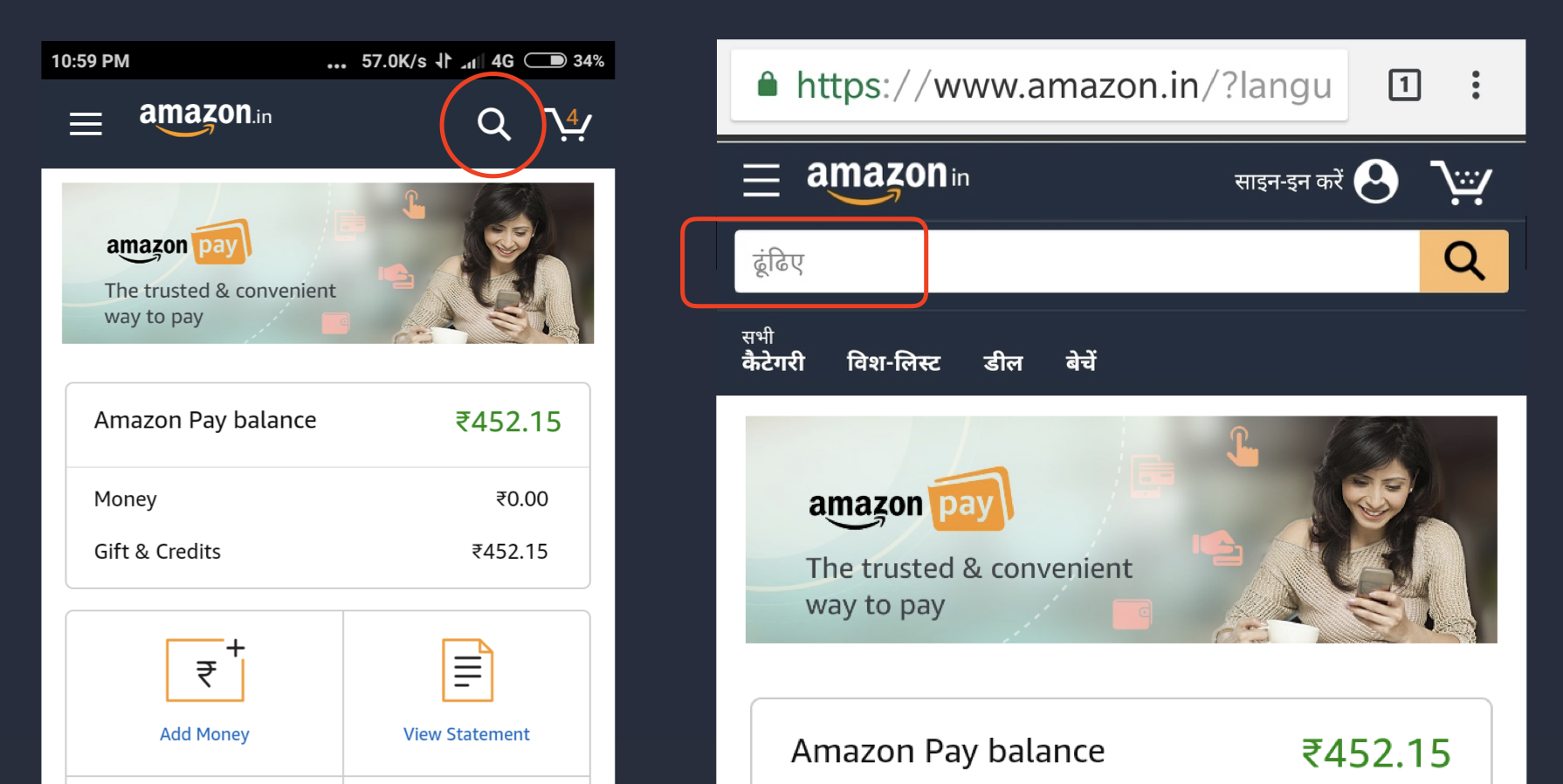

When launched in India in late 2018, Amazon was faced with a serious problem caused by a lack of cultural insight and comprehensive UX research. They couldn’t figure out why customers in India weren’t using one of their primary drivers for revenue: searching for products to buy on the homepage of the mobile site. It turned out that the magnifying glass icon was not something people associated with search in India. It made no sense at all to them.

When the UI was tested, most people thought the icon represented a ping-pong paddle! As a solution, Amazon kept the magnifying glass but added a search field with a Hindi text label to let people know this was where they could initiate a search.

When designing cross-cultural products, designers not only have to contend with different languages, dialects, and dimensions of national culture but also cultural differences in color psychology and mental models. Furthermore, reading direction from culture to culture adds another layer of complexity as text can be written left-to-right (LTR), right-to-left (RTL), and top-to-bottom.

With some languages, “mirroring designs” is something designers need to consider when designing for both LTR and RTL languages. Consideration should be given to everything from text to images, to navigation patterns and CTAs (calls-to-action).

Here’s Facebook’s homepage in English:

And here’s Facebook’s homepage in Arabic where the layout is reversed (mirrored):

Using culturally appropriate imagery in products reaching across cultures is also something designers need to be aware of. An image that may be perfectly acceptable in Western cultures may be considered inappropriate in some Middle Eastern countries. Varying attitudes towards gender, clothing, and religion in different parts of the world call for designers to be extra careful when working with images.

If a designer is not familiar with a particular culture, it’s crucial that they dedicate some time to researching what is appropriate in tone from culture to culture, being sure to include every element in the UI: text, imagery, iconography, microcopy, and more.

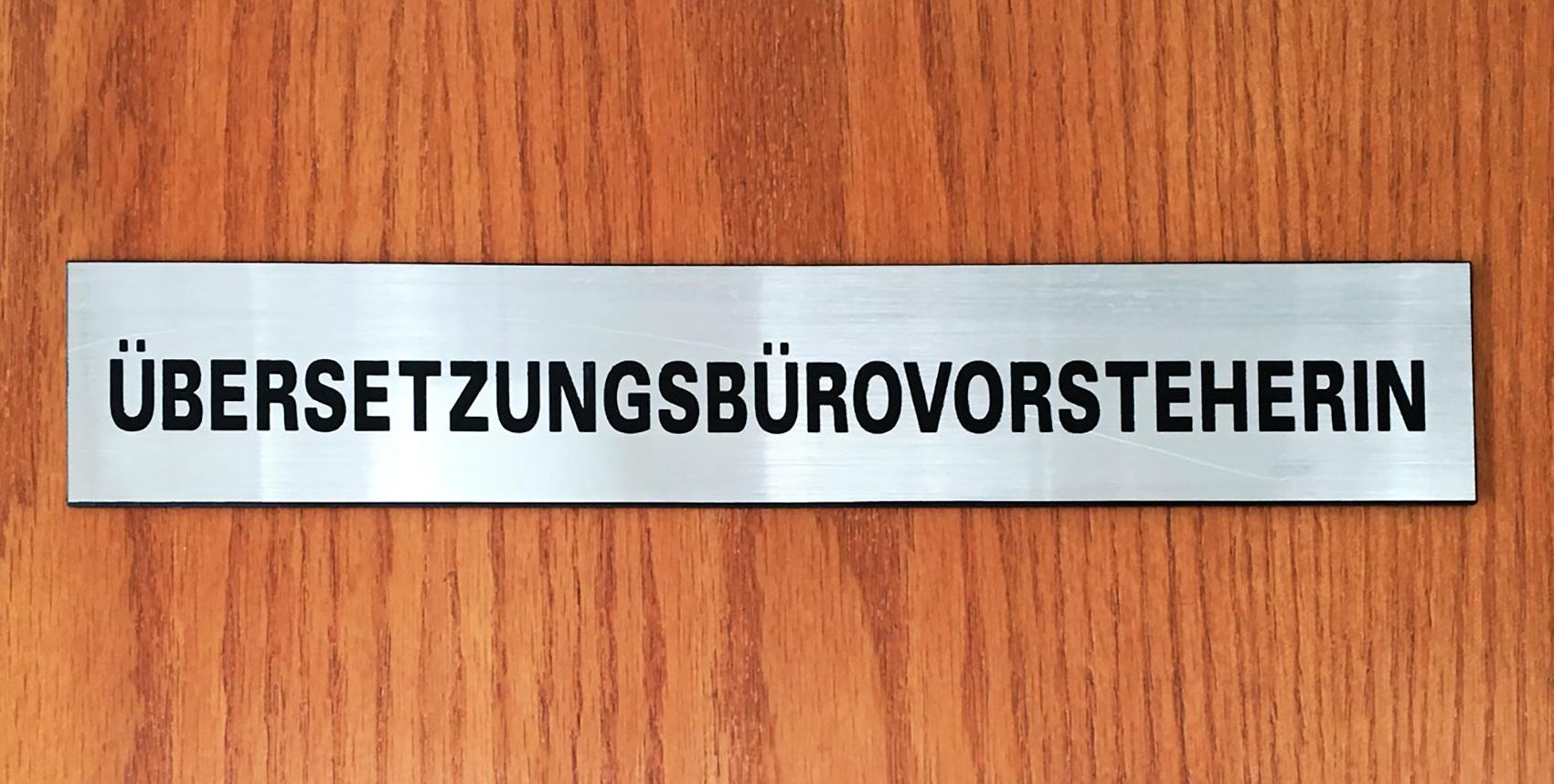

Designers also have to account for text in different languages, known as “text expansion.” Working with English, German, and Japanese for the same piece of text will yield very different results. Going from English to Italian phrases will at times cause text expansion of around 300%! Not accounting for differences in word lengths in a variety of languages or giving UI elements ample padding will create a boatload of work down the line because a tsunami of screens will need to be adjusted to accommodate the switch to another language.

The seven dimensions of cross-cultural design

Designing for global markets has been around for a long time and predates designing for digital products. Cross-cultural design research is rooted in the work of two individuals: Fons Trompenaars and Geert Hofstede.

Trompenaars is widely known for “The Seven Dimensions of Culture,” a model he published in “Riding the Waves of Culture.” The model is the result of interviews with more than 46,000 managers in 40 countries.

Rather than distinguishing cultures simply by language, Trompenaars established seven differentiating qualities:

- Universalism versus particularism. Do people place value on rules, laws, and dogma? Or do they believe the world to be circumstantial?

- Individualism versus communitarianism. Do people believe in personal freedom and achievement? Or is the group greater than the individual?

- Specific versus diffuse. Are work and personal lives kept separate or do they overlap?

- Neutral versus emotional. Do people make great efforts to express their emotions or are they kept in control?

- Achievement versus ascription. Are people valued for what they do or who they are?

- Sequential time versus synchronous time. Some people like events to happen in a striated sequence. Others believe that the past, present, and future are an interwoven continuum.

- Internal direction versus outer direction. Some cultures profess to control nature and the environment, while others believe the opposite.

Hofstede also contests conventionally narrow views of language and culture. Everyone knows that our spoken accents develop based on where we grew up. Less talked about, though, is that how we feel and act is also a type of accent influenced by our locale.

The cultural dimensions represent cultural tendencies that distinguish countries (rather than individuals) from each other. The country scores on the dimensions are relative, as we are all human, and simultaneously we are all unique. In other words, culture can be only used meaningfully by comparison.

How cultural dimensions may influence design

Let’s look at three examples in cultural differences with regard to how people respond to authority, whether people see themselves as individuals or a part of a group, and how comfortable people in different cultures are with uncertainty. The examples cross into cross-cultural user experience design and behavioral design and are all aspects to consider when designing for different cultures.

How do users respond to authority?

Hofstede placed every country somewhere on his power distance index (PDI), which measured how societies accept power inequality. Some cultures expect information to come from an authoritative position, whereas others put less stock in expertise and certification.

The implications of this for digital design are that authoritative language or imagery may perform well in high-power distance cultures, but users in low-power distance cultures may respond negatively to the same and would prefer to see something closer to the less informal popular imagery of everyday life.

Do people see themselves as individuals or as part of a group?

How do we motivate people in an individualistic culture versus a collectivist one? Does our product promote individual or collective success? How do we reward users? Some societies place importance on youth, whereas wisdom and experience are valued elsewhere. Hofstede measures this on the individualism vs. collectivism index (IDV). Countries with high numbers on the index are more individualistic.

How comfortable are people with uncertainty?

When it comes to the uncertainty avoidance (UAI) dimension, cultures that rely less on rules and rationality respond to more emotional indicators. Conversely, a society that is uncomfortable with uncertainty prefers clear and distinct choices. How do these different cultures react to something unexpected, unknown, or away from the status quo?

For example, Germany scores high on the IDV index; therefore, it typically avoids uncertainty. Accordingly, products designed for Germany, for example, should give people a rational sequence of decisions to make. Countries that are lower on the scale can provide people with more freedom and a relaxed exploration of the product with more emphasis on emotion.

What about risk aversion in a culture? For instance, if acutely risk-averse Japanese customers are required to submit their credit card information immediately during registration for an eCommerce site, it will most likely result in a high rate of abandonment.

The importance of user research in cross-cultural design

Gaining micro-level insights through direct observation is at the center of human-centered design thinking methodology. When engaging in cross-cultural design projects, proper user research is vital for achieving frictionless digital user experiences across borders. Typically, this means getting out into the field to meet people where they live and work, which helps designers understand particular needs and imagine pertinent future possibilities.

People in diverse cultures interact with information in different ways. People in Russia are used to different cultural conventions when using digital products, as opposed to people in Egypt. The need for designers to thoroughly research and understand local customs, cultural dimensions, cross-cultural psychology, and local UI patterns cannot be understated as it will either lead to success or result in failure.

Research may involve looking into the primary devices used by the target market and potential challenges with internet connectivity. With less powerful devices on poor network connections, designers could take advantage of AMP technology (accelerated mobile pages), use adaptive design, or use progressive web apps to speed up mobile sites. They can also design mobile apps in a way that detect poor network connections and subsequently serve up stripped-down core functionalities, allowing them to work offline or with spotty connections.

Additionally, not only is it essential to have a local native speaker check appropriate language, it’s equally important to have a content specialist perform cultural checks. This includes checking images, colors, abbreviations, phrases, and idioms to make sure they’re culturally appropriate and resonate with the local audience.

To dig deep into local customs, behaviors, and attitudes, it’s best to do both qualitative and quantitative research. Qualitative UX research may involve interviews, intercepts, and contextual observations, ethnographic studies, and field studies; quantitative research may include competitive analysis, secondary research, and surveys.

Qualitative user research is a direct assessment of behavior based on observation. It’s about understanding people’s beliefs and practices on their terms. For example, observing people in their natural environment gives designers a better understanding of the way people live and use digital products, which helps them design products that are genuinely relevant to them.

Quantitative research is primarily exploratory research and is used to quantify the problem by way of generating data that can be transformed into useful statistics. Some conventional data collection methods include various forms of surveys, longitudinal studies, website interceptors, online polls, and product usage analytics.

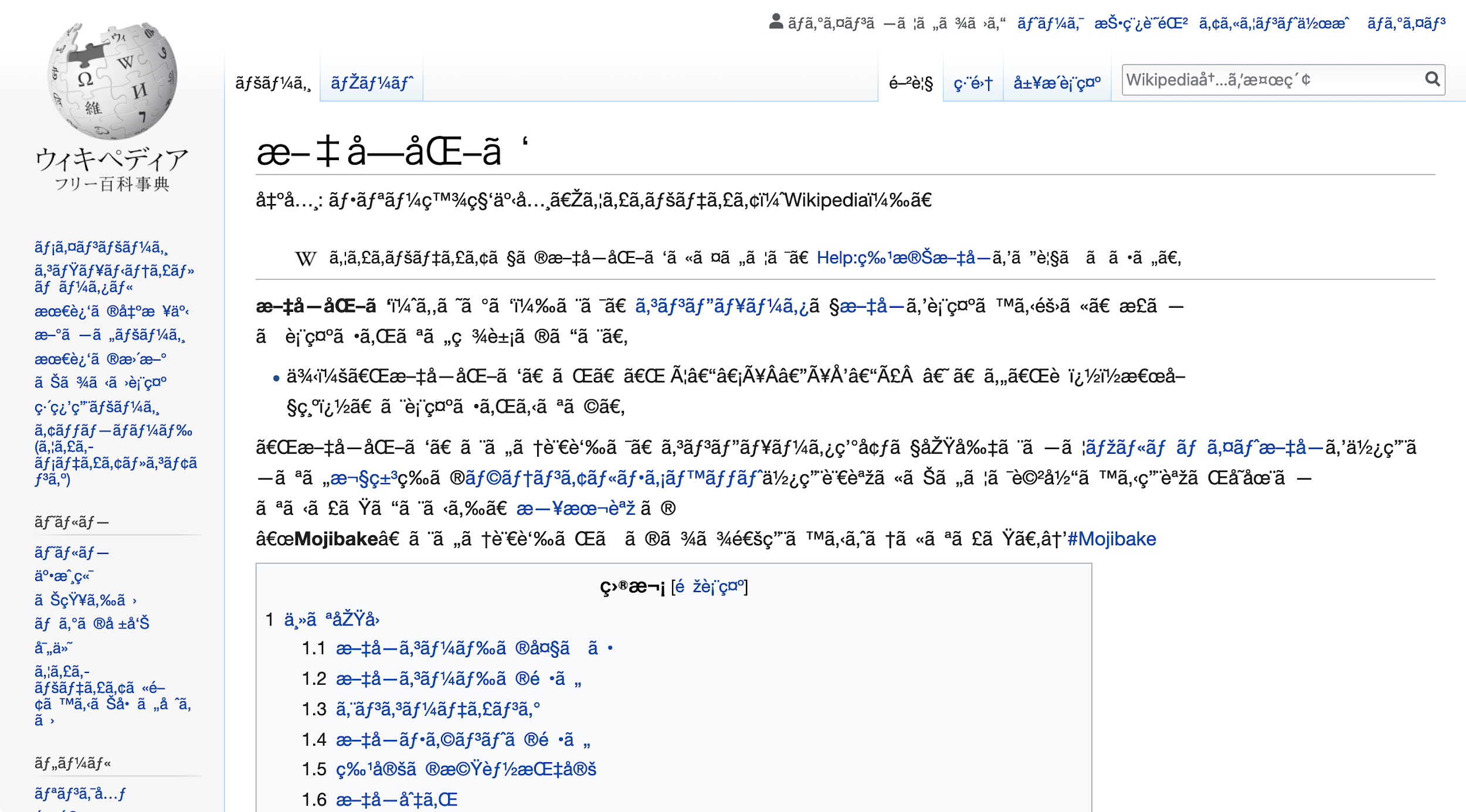

Looking at the practical side of a cross-cultural design project, designers need to dedicate a considerable amount of time to select the best design tools. Many design tools don’t offer full support of fonts, or certain characters for a variety of languages; for example, Russian Cyrillic, Japanese, Arabic, or Chinese. Designers need to carefully consider their design tools and workflow (especially if using multiple design tools) and their final deliverables. Testing the cross-cultural design workflow during the early stages of the project is crucial.

Some foreign language fonts may work on the desktop in a design tool but will not render as intended on the web with the web font version. Web fonts include support for many different languages, but not all, therefore, designers will need to carefully select fonts that support a particular language or script. Consulting with developers early about character encodings, using web fonts, and font embedding depending on the type of digital product (site or app) will later pay off in spades, as will extensive testing and QA.

Cross-cultural design is not a walk in the park. Designers not only have to contend with various cross-cultural design challenges but also often have to bridge the cultural divide with clients in terms of communication styles, wrestle with design tools and web browsers not rendering fonts or foreign language characters correctly, text expansion in various languages, and issues using their keyboards to input and edit a variety of languages.

Working across borders between designers and clients may present another set of challenges. For example, the author (a Brazilian designer) worked on a project with a Russian client and had to actively engage the cultural divide between the client and himself throughout the design process to avoid any misunderstandings.

When it came to working on the project, issues occurred with Cyrillic fonts in different design tools not rendering correctly. Without a Cyrillic keyboard for text input and edits, an on-screen Cyrillic keyboard had to be used, which slowed things down dramatically.

Cross-cultural design needs special attention

As many companies continue to explore global business opportunities, they will be challenged to adapt to the local characteristics of various new markets, the sociopolitical environment, and the cultural system. Understandably, global business leaders want to get their products to the market as quickly as possible, but in order to offer best-in-class user experiences, cross-cultural design requires special attention. Great UX is rooted in the careful examination of social and cultural context, and often it’s up to the designers to put the brakes on and call for a slowdown.

An essential part of the design thinking process is performing in-depth UX research: exploring what people say, think, do, and feel to uncover fresh insights that help design human-centered solutions. Expert UX designers know design projects that cross borders need to be researched and tested thoroughly.

Designers have always risen to the challenge as they work at the intersection of cultural and technological trends, whether in digital or physical products. When done well, a carefully executed product design will resonate with the culture of the audience that it was intended for.

Cross-cultural design invites designers to embark on a road less traveled. At times it may become a little bumpy. As long as designers understand the seven cultural dimensions, seek an informed perspective, and investigate the best workflows, tools, and processes, they will complete the journey successfully.

The Toptal Design Blog is a hub for advanced design studies by professional designers in the Toptal network on all facets of digital design, ranging from detailed design tutorials to in-depth coverage of new design trends, tools, and techniques. You can read the original piece written by Jon Vieira here. Follow the Toptal Design Blog on Twitter, Dribbble, Behance, LinkedIn, Facebook, and Instagram.

Published May 29, 2020 — 06:00 UTC