When we spend so much of our time online, we’re bound to learn something while clicking and scrolling. Discover something new with Mashable’s series I learned it on the internet.

I’ve never felt more like a hungry squirrel than when I spoke to a neuroscientist who’s spent decades studying, and trying to expand, human attention spans.

Just like a squirrel forages for nuts, he explained, humans forage for information. As a squirrel hops from tree to tree to gather food — even if the tree it’s hanging out in has plenty to offer — humans hop from information source to information source. We get bored of our metaphorical nuts, or we get anxious that the other tree’s nuts are better, and bouncing over there is a breeze.

Yes, I thought, I’m a ravenous squirrel nibbling on tabs, links, Instagram posts, memes, tweets, TikTok videos, Slack notifications, emails, and text pings. I pictured myself looking like this little guy below, as Dr. Adam Gazzaley, founder of UCSF’s neuroscience center Neuroscape, made the comparison.

But, while I’m getting cocky gliding from tree to tree — hey, I must be decent at hopping about since it feels pretty good — I’m also feeling fatigued and forgetful. What was it that I was originally trying to do before I ended up on Wikipedia again? Why am I exhausted at the end of the day, even though I only got two things done?

The plentiful forest of the internet has tricked me, and probably you, too, into believing that we’re good at multitasking. Not just good, but getting better at it over time. I learned how to harvest the internet clickfield by doing as much as possible side by side. While working, always with multiple tabs going, I’d watch CNN and text and Slack and read Google News. While relaxing, I’d watch Hulu and read cookbooks, or listen to a podcast and scroll through Twitter, or call my mom and look at Instagram (sorry mom). I thought I’d become a multitasking machine.

But cognition experts are quick to point out that the more I multitask online or off, the worse I am at it, and everything else I’m trying to accomplish.

“It’s not a skill you can acquire,” said Dr. Dave Strayer, who has a doctorate in psychology, and through his work at University of Utah helped build an online multitasking test that mirrors his lab research.

Thinking back on me as a puffy-cheeked squirrel, you may wonder, wait, isn’t the nut analogy more about distraction than multitasking? Well, the two aren’t too far removed. A distraction is background noise you’re trying to ignore, like when there’s construction outside and you’re trying to read about eager squirrels. Meanwhile, multitasking is when you choose to engage with a distraction, like when you’re watching a squirrel documentary on Netflix, but then you decide to Instagram lurk at the same time — or when you Slack your coworker a squirrel emoji while you’re trying to file an expense report.

“Distraction degrades our performance all the time,” Gazzaley said, underscoring that it gets worse as we get older (ugh). “Distraction degrades it less than multitasking. The minute you decide, you make a decision to actually try to do both and fragment your attention, then your performance drops even more.”

Strayer’s found it takes three to four times as long to attempt to do two tasks simultaneously compared to doing one after the other. It can take 20 to 25 seconds to switch from task to task, he said. All those pauses add up.

How technology has tricked us

The internet and its progeny, like smart car dashboards and buzzing smartphones, are built to make it seem like they can help us multitask, but our brains just aren’t cut out for it.

“It leads us to try to engage in multiple information-demanding activities simultaneously, and that is what our brains just do not do very well. They weren’t evolved for that very type of demand,” said Gazzaley, who also wrote The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World.

Our brains suck at multitasking, but they sure like it. Every time we multitask and get a quick burst of new information, we’re rewarded with a shot of dopamine, which makes us happy.

But all that task-switching is exhausting. And the fatigue may cascade into other parts of our lives, Gazzaley said, possibly souring our moods, amping up our anxieties and stressors, and ruining our sleep.

Throughout his career, he’s been surprised by how little we pay attention to brain fatigue, both in scientific circles and among self-help book gurus.

“Every athlete is a master of physical fatigue. It’s not a sign of weakness. It’s just part of what the body does. You have to understand your fatigue so that you know how to restore and engage again,” he said. “With cognitive fatigue, my observation is that it’s not embraced that way. It’s not understood to the same depth scientifically and becomes something that we view as a weakness.”

Cutting back on multitasking isn’t enough to combat cognitive fatigue, he advised. Rather, you need a “real top-down break,” which may include incorporating quiet, eyes-closed pauses into your day, nature walks, and light exercise.

“It’s not necessarily a badge of courage if you multitask a lot, because you probably are not very good at it.”

Multitasking is often listed as a job skill, both by candidates and employers, when it shouldn’t be something we brag about or seek out, Strayer said.

“It’s not necessarily a badge of courage if you multitask a lot, because you probably are not very good at it,” he said. “And it probably means you are more impulsive and sensation-seeking.” It’s also likely curbing your short-term memory. Ever been clicking from tab to tab and forgotten what you were doing in the first place?

There is, however, a sliver of people who are good at multitasking; Strayer calls them supertaskers. More than a decade ago, Strayer and other researchers studied how talking on a cellphone impacts driving, and nearly every participant was scoring badly (using your phone makes you a worse driver, even if it’s hands-free). One person appeared to be thriving while multitasking, though. Strayer and his colleagues thought their results must be a mistake, but after testing hundreds of people they discovered that about 2 percent can multitask well. He later developed an online multitasking test with Australian researchers. More than 10,000 people have taken it over the years. He still gets roughly the same percentage of supertaskers among the larger pool.

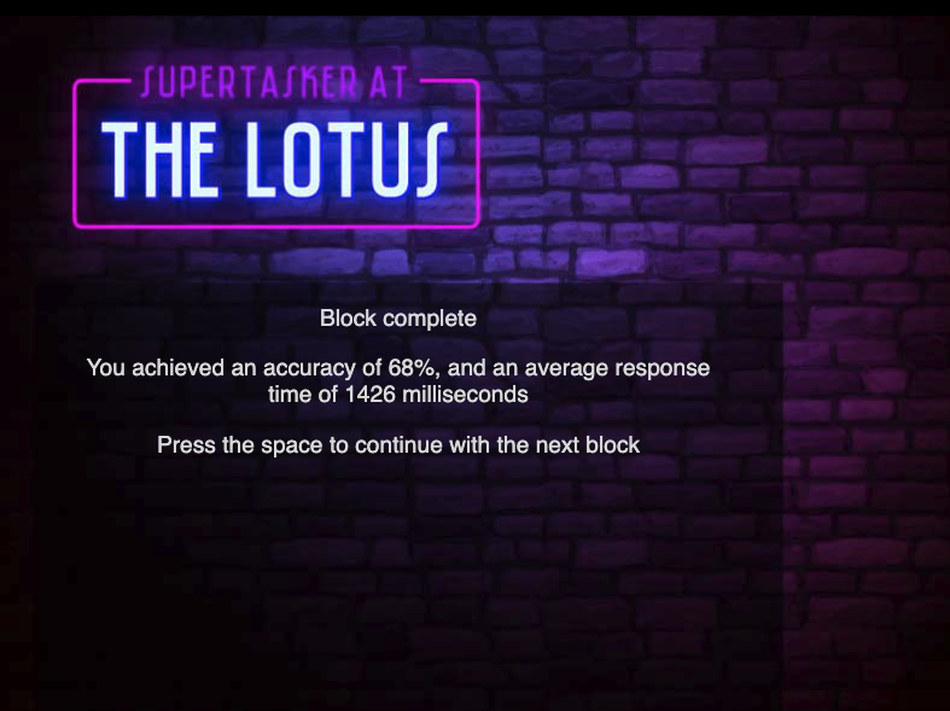

The 40-minute test has you pretend to be a bouncer at an exclusive club managing multiple doors and passwords. Australians love clubbing and Strayer’s colleagues there came up with the theme, he quipped. Despite the fun concept, the test made his brain hurt. Mine too. I didn’t do so well at the beginning, but got better as the test continued, eventually getting an 84 percent. I was still not a supertasker, and my improvement can probably be attributed to misunderstanding the rules at the start. Supertaskers get perfect scores, or close to it.

My first attempt to see if I was a supertasker.

I was getting better, but mostly because I understood the mechanics and rules more by the end.

Supertaskers tend to be extraordinary at their jobs: They’re expert piano sight-readers, NFL quarterbacks, fighter pilots, Olympians, and high-end chefs. There is no difference when it comes to gender or geography. Brain scans have shown that when a normal person takes a supertasking test, blood rushes to the area behind the center of their forehead as that region works super hard. That doesn’t happen to supertaskers. For some unknown reason, their brains get more efficient as their attention splits.

“Some people say, ‘I can’t believe this. I’m a really good multitasker,'” Strayer said of those who score poorly and email him to complain. Strayer compares it to when you see a driver swerving while talking on the phone. You grumble about how bad they are at driving, and yet you still drive and talk on the phone at the same time.

“It’s that disconnect. We think everyone else who’s driving and on their phones is idiotic, but we don’t think we are,” he said.

Sadly, you can’t become a supertasker with practice. You’re born one. The rest of us will have to find other solutions to curb our multitasking even as the internet lures us off target.

How to fix the problem

We can’t put “the technology genie back in the bottle,” Gazzaley said, but there are ways to break the bad habit of multitasking. As with most bad habits, the first step is recognizing the problem.

“It’s really hard to change habits, especially when it involves your job and social life,” Gazzaley said. “The first step is to inform yourself. [Multitasking] is impacting your sleep, your work productivity, it’s impacting your social life and your deep intimate relationships. If you don’t realize, ‘Oh this is really not the best way to interact with technology,’ then there’s no chance of changing it.”

Once you truly absorb that, you need to take steps to manage your access to information. “When we get these systems, we don’t customize them, so we let them take over,” Strayer said of our smart devices and general internet use, giving the following advice:

-

Change your email settings so you only get deliveries once an hour or twice a day.

-

Set your phone to automatically enter driving mode while in the car, limiting its use.

-

Turn off phone notifications.

-

Practice the Pomodoro technique of working for 25 minutes on a task, then taking a 5-minute break. Do that four times, and then take a longer 20-minute break. Do that all over again.

I removed Twitter and Instagram from my phone on New Year’s Day. While that stopped me from second-screening while watching TV and talking to people, it also made me feel very uncomfortable. I was so used to streaming a show while tapping through Instagram Stories that I felt bored. I still haven’t gotten past the feeling of itching to do more.

“We accumulate boredom… We think, ‘Am I really being productive right now? I must have the ability to do this and this.’ You’re feeling this anxiety that’s not related to anything real,” Gazzaley said.

Training to improve attention

Gazzaley has built video games to beef up attention spans. His company, Akili Interactive, released the first FDA-approved prescription video game for children with ADHD that improves the quality of their attention both in and out of the game.

[embedded content]

Unlike my multitasking of answering questions on Slack while in meetings, Gazzaley’s game, EndeavorRx, forces the player to do more brain-taxing tasks while ignoring distractions. The player is an alien on a hoverboard zooming down a river. They have increasingly challenging jobs to do and speed to manage, as they ignore distractions — you have to collect some colorful fish but ignore others, for example.

Gazzaley believes these kinds of games can one day help everyone, not just children with ADHD. They won’t make you better at multitasking, but they’ll improve your focus outside the game as you choose to single task.

The game also won’t curb the desire to multitask. “It’s not enough to have a better ability to deploy attention if you don’t know how to do it or you still haven’t broken those other habits,” he said.

So before all us squirrel friends (this kind of squirrel friend, too) get excited about one day using a video game to improve our focus, know there’s no tech that’ll make us want to take advantage of our new skill. Focusing on single-tasking instead of engaging with many layers of distractions is something we’ll have to work through on our own.

Curious if you’re a supertasker? Take the online test to find out.