Mashable is celebrating Pride Month by exploring the modern LGBTQ world, from the people who make up the community to the spaces where they congregate, both online and off.

As well-intentioned as Pride merchandise may be, mullets and cuffed pants capture the “queer aesthetic” far better than anything dripping in rainbow logos. But that doesn’t mean they’re safe from rainbow capitalism.

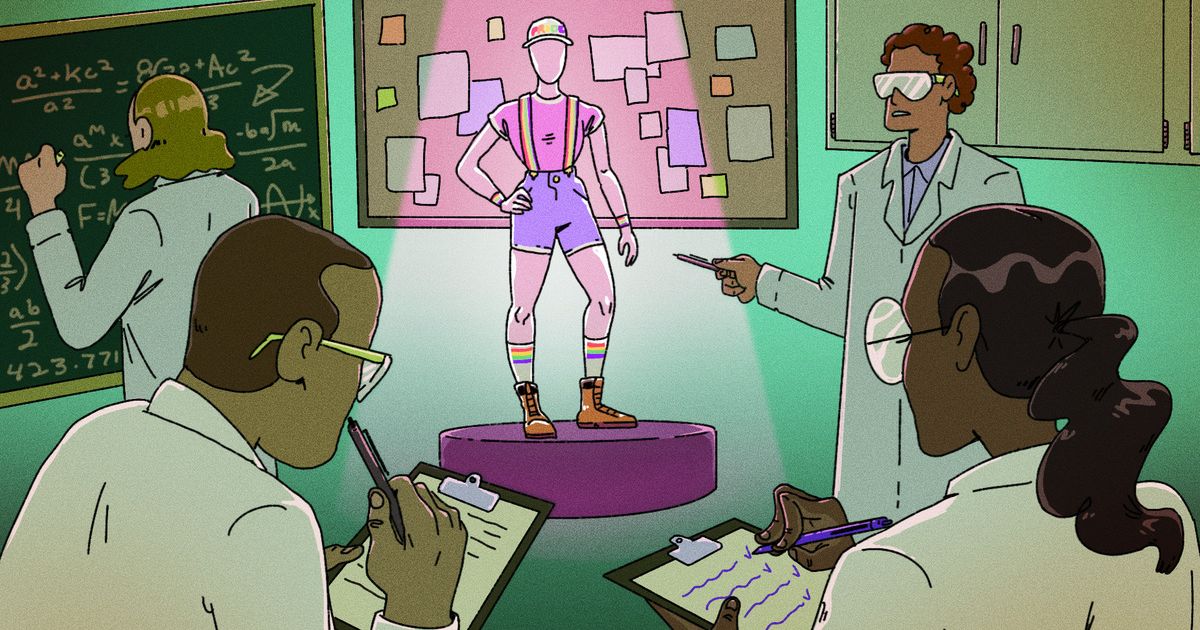

In a TikTok posted in April, Giulia Beaudoin asked viewers why a mirror selfie of someone with green hair, wire rimmed glasses, and black high-top Converse is “so much more gay” than a photo of herself dressed in rainbow suspenders and a hat emblazoned with “PRIDE.”

“Yes, this was me two years ago, but this should be gay,” Beaudoin posited. “This should be so much more gay than the other picture, but it’s not. It’s just not.”

One comment likened the first image to attending a college and the second to wearing the college’s merchandise. Another described the first image as an “authentic LGBTQ person in their full self expression” but the second as “giving Target Pride section.” Other comments described the second image as “commercialized queer,” “like a tourist,” and “how straight people dress when they’re trying to be supportive at Pride.”

Monetizing rainbows

Rainbows have been a symbol of LGBTQ rights movement since the first iteration of the rainbow flag was flown at the San Francisco Gay Freedom Pride Parade in 1978. The United States has made significant strides in ensuring LGBTQ rights since, from the 2015 federal legalization of same-sex marriage to the Equality Act passed by the House of Representatives this year, which would explicitly shield individuals from discrimination based on sexual orientation. (The legislation still needs to pass through the Senate, provided it isn’t stymied by Republicans.)

But since the first rainbow flags flew in the 70s, Pride celebrations — and the abundant rainbow iconography that accompany them — have come to be associated with commercialization, not liberation. Gen Z is the queerest generation yet; a Gallup poll published this year concludes that nearly one in six of respondents age 18 to 23 identify as queer or transgender. On social media, though, LGBTQ people are reluctant to embrace rainbow merchandise with the same vigor that companies seem to produce them.

Target’s Pride merch, for example, was the laughingstock of TikTok for weeks. The company’s garish apparel and LGBTQ flag home decor sparked a TikTok trend of criticizing other corporations’ Pride wares. This generation of young adults may be the most openly LGBTQ, but many are disillusioned by “rainbow capitalism,” a phrase to describe the way LGBTQ liberation is monetized and used for social capital. Alex Abad-Santos described Pride as a “branded holiday” in a 2018 Vox piece, writing that the annual practice of pumping out rainbow products and donating a fraction of the proceeds “creates a context of so-called slacktivism, giving brands and consumers alike a low-effort way to support social and political causes.”

In other words, it’s lazy.

Fashion and identity are linked

Beaudoin, who is a student, does not dress in rainbow suspenders or paint rainbow hearts onto her cheeks to celebrate her sexuality anymore. Instead, she told Mashable via Instagram DM, she expresses herself by dressing in the “queer aesthetic,” trading Pride merch for flared jeans and loudly printed coats. She added that most of her straight classmates opt for more mainstream clothing choices like sweatshirts and leggings, but she never goes to school “in a basic outfit.”

“Even though that’s fine, I like to stand out!” Beaudoin said. “I think this has to do with the fact that I’ve gotten comfortable with my sexuality because it allowed me to take the same principles I learned and apply them to different areas. I learned a lot about self-expression while figuring out my sexuality and now I use that with my fashion!”

“Those things weren’t designed for gay people.”

She noted that while rainbow merchandise “can show that someone is LGBTQ or an ally,” other ways of expressing gender and identity appear more authentic, since “those things weren’t designed for gay people.”

The “queer aesthetic” is less of a defined style and more of a philosophy of presenting oneself; it proudly veers from conventional trends in favor of ones that subvert social niceties. The aesthetic ranges from the flamboyant to the austere, but regardless of visual presentation, each article of clothing or accessory is worn with intention. Styling yourself through a queer lens is a subtle signal to other queer people that you are part of their community.

Sonny Oram, a queer fashion activist and founder of the fashion incubator Qwear, noted that most alternative fashion originated in queer communities first, particularly in Black trans circles.

“Fashion is just such an important part of who we are. That’s the first time you tell someone, ‘I’m not straight.”

“Fashion is just such an important part of who we are,” Oram told Mashable in a phone call. “That’s the first time you tell someone, ‘I’m not straight.’ I think when we know that the mainstream society rejects us, or doesn’t welcome us, we kind of naturally gravitate towards style worn by people who will accept us.”

Oram added that gravitating toward certain styles that encompass the amorphous “queer aesthetic” can be subconscious, which it’s common for young people to dress a certain way before coming to terms with their own sexuality or gender identity.

“I think a lot of it happens on a subconscious level sometimes, like, ‘Oh I don’t feel welcome there, so I’m going to wear this,” Oram continued. “Because this makes me feel comfortable without even necessarily knowing that you’re queer.”

Fashion as a secret code

Using covert ways to signal belonging to the LGBTQ community is woven into queer history. Coming out or being outed non-consensually is a risk today, but was even more dangerous decades ago. LGBTQ people relied on using coded phrases to come out to each other. Terms like “family,” “a club member,” or “a friend of Dorothy’s” were used to describe themselves or another person as gay. The word “gay” itself was a one of these code words, and was originally co-opted from a phrase female sex workers used to refer to each other. The gay rights movement “outed” the word following the rebellion at the Stonewall Inn in 1969, University of California, Los Angeles sociology professor Abigail Saguy wrote in the Conversation. Gay men employed the “handkerchief code” to signal sexual preferences, and the beloved caribiner is a universal visual cue for lesbians.

Dr. Sharon P. Holland, the chair of the American Studies department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, researches feminist, queer, and critical race theory that draws from her experience as a Black gender non-conforming woman. The history of flagging, she said, still manifests in the way queer people present themselves today.

“Back in the day when there were pubs and bars that were on the down low, a color suggested…that you were a top or bottom. You could more easily partner with people,” Holland told Mashable during a phone call. and added that though less explicit, the way people dress now can indicate that they’re LGBTQ. “Gender and sexuality has become a style for us.”

Fashion, in addition to being a gender-affirming visual presentation or expression of identity, is just as much of a coded flag. Of course, nobody should feel pressured to present as “visibly queer.” Some are uncomfortable with diverting from the mainstream, and for many, it’s a matter of safety. The “queer aesthetic” itself, which is largely embraced as a more authentic representation of LGBTQ communities than the rainbow flag, is subject to commodification as well. Cuffed jeans and oversized earrings may have been more “queer” than a rainbow “Girlboss” shirt, but those cues can still be monetized.

In an essay for the magazine Off-Kilter, Leyla Moy criticized the “queer aesthetic” norms of women in cuffed jeans and men in floral suits as “palatable, slight variations on trends that do represent increasing acceptance of visible gayness and gender noncomformity, but only to the extent that it minimally challenges heterosexual expectations.”

Harry Styles, for example, is heralded as a queer icon for walking red carpets in flamboyant, gender nonconforming outfits. He famously enraged conservatives by wearing a Gucci gown and jacket on his December 2020 Vogue cover. TikTok star Noah Beck posed in fishnets and heavy black eyeliner for VMAN in March this year. Promotional content for Darren Criss’ recent single “I Can’t Dance” features the artist in heeled black boots and an electric green coat.

The rise in prominent public figures testing the boundaries of gender norms provoked discourse over who can present themselves this way. Critics accused Styles, Beck, and Criss of “queerbaiting,” a marketing tactic that leads fans into falsely believing celebrities or fictional characters are LGBTQ because of the way they dress or interact with members of the same sex. Like rainbow Pride merch, it is often a disingenuous appeal to queer communities that doesn’t actually involve doing anything to represent or uplift them.

not noah beck getting praised for ‘breaking gender norms’ by wearing heels and eyeliner like he hasn’t been queerbaiting, making fun of feminine mannerisms and liking homophobic posts

— daniel (@anextremeside) March 4, 2021

Praising cishet celebrities whose outfits diverge from the heteronormative — or in the case of pop stars like Taylor Swift and Ariana Grande, make veiled references to same-sex relationships — is a hollow attempt at LGBTQ progress if those celebrities don’t identify as queer. That’s not a reason to write them off entirely, though. Rupi, Oram’s partner and fashion director at Qwear, pointed out that the fashion industry “has become more comfortable with mixing gendered items” in the last decade, and that unisex styles are more prominent than before thanks to a cycle of public figures normalizing crossing the binary. It would be unfair to praise Styles and other cishet celebrities as trailblazers, but their willingness to play with traditionally gendered clothing makes it safer for LGBTQ people to publicly exist.

“Queerness in general has become more accepted by the mainstream and I think that fashion always came from queerness.”

“I just think it’s not cool to oppose anybody who wants to dress in any way. I feel like opposing anybody’s form of dress can be problematic,” Rupi said, adding that fans could appreciate Styles’ outfits while still honoring the activists who made it possible. “Queerness in general has become more accepted by the mainstream and I think that fashion always came from queerness. It was really the Black trans women who started all these styles.”

Subverting the norm

The “queer aesthetic” may not be a personal style, but it is a subversion of heterosexual norms.

Holland remembers using kissing at the height of the AIDS epidemic to signal a distinct otherness. Regardless of gender or sexuality, Holland told Mashable, her circle of cis gay men, cis lesbian women, trans friends, and straight allies would greet each other by kissing on the lips. The beauty in it, she said, was that it made “straight people around us very uncomfortable” because “they couldn’t tell who we were at that point, and who we were to one another.”

“Even though it was unsafe for us to do some things in public, at the same time, we engaged in activities that were public facing that mixed things up,” Holland recalled over the phone. “We’d all be together on our way to the club, maybe going to a house party, meeting up for coffee, and we’d engage in this activity of kissing one another.”

Holland said that onlookers were confused, as the perception of LGBTQ people was even more binary than it is today. The public displays of affection subverted the notion, and clearly showed visibly queer people engaging in “straight” activity.

“There was safety in that they knew we were probably not straight,” Holland continued.

And although the country is much safer for queer people to openly exist in today, LGBTQ rights are threatened every day — Black trans women started the LGBTQ liberation movement, but Black trans women today are disproportionately targeted by hate crimes. Though queerbaiting claims and arguments against the commodification of the “queer aesthetic” are valid, Holland marvels at the fact that her children and their friends can safely experiment with their style because subverting the heteronormative is so normalized.

“As someone in the older generation…I tend to give a wide berth to our youth while they’re figuring themselves out because I think that is how we’re going to have the healthiest [understanding of] sexuality for everyone,” Holland said. “We just let people do their thing.”