On May 25th, the police killed George Floyd, and in every state, protests against police brutality and anti-black racism have been ongoing ever since. For reasons that risk trivializing a serious moment in history, the brands have also decided to speak up, too, issuing statements of solidarity across social media platforms. This, for better or worse, is to be expected: we live in the age of the Brand Statement, and brands acknowledging people as more than just potential sales is better than pretending nothing is happening in the world.

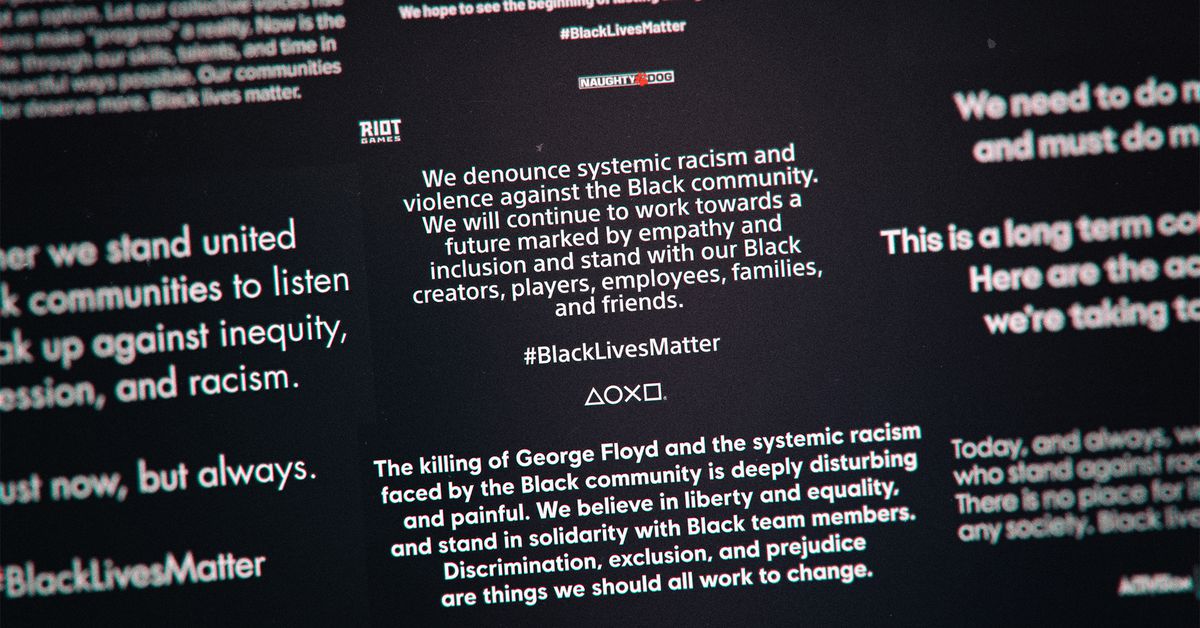

Video game companies, however, are uniquely bad at this. Most statements made by the makers and publishers of games are boilerplate: companies like Sony, Microsoft, and Nintendo decry racism, affirm the need for inclusion and equality, and often directly address “the black community.” A few, like publishers Ubisoft and Activision, even say “black lives matter” outright, instead of rephrasing it in corporate-speak.

In a piece for Vice, Gita Jackson writes about how these statements aren’t just the bare minimum. They’re clueless and hollow, unwilling to confront their complicity and center the conversation on anti-black racism — while also lagging behind companies like luxe exercise bike brand Peloton in both timing and charitable donations.

It’s abject cowardice in the service of capitalism, where a white supremacist’s dollar is just as good as yours or mine

“Even when companies name the issue, it still doesn’t hit right,” Jackson writes. “I am glad that Ubisoft specifically named George Floyd and systemic racism, but one of the largest companies in the industry is giving less money to the NAACP than a fancy exercise bike company. And how can I trust anything they say about anything while they use their license of Tom Clancy’s work to make games about DEA agents shooting up drug cartels and American ‘sleeper cell’ agents taking back the streets from looters and violent Rikers inmates?”

Statements of solidarity from corporations are not unreasonable, even if they are from for-profit institutions that benefit from the labor, patronage, and support of oppressed people. But they’re also the product of strategy, one for which there is currently no blueprint. Consider this report from Kotaku’s Ethan Gach, who compiled the statements made by prominent gaming companies and followed up to ask what actions were planned to enact meaningful change. While the best of the gathered statements commit to making donations to charitable organizations, none would give an answer when asked by Gach about further plans for direct action or lasting changes.

While these statements are, quite literally, the least a corporation could do to address the cultural moment coalescing around the confrontation of racism and police brutality, it was not that long ago where video game companies could not be bothered to do even that. We’ve been here before, specifically in August 2014, when Ferguson, Missouri police officer Darren Wilson killed Michael Brown.

From August 10th through August 25th, 2014, the first wave of protests — and the violent police response to them — swept Ferguson. These two weeks of protests mainstreamed the Black Lives Matter movement, which formed in response to the murder of Trayvon Martin by neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman the year before. During this period, the United States was rocked by live footage of the militarized police response to black protestors, and video game corporations carried on in their own little world. For video games, it was business as usual: hype for games revealed at E3 two months before; more marketing hype coming from the annual Gamescom convention in Cologne, Germany; first looks and detailed reports about upcoming games that are frequently oblivious to the world around them and occasionally astounding in their tone deafness.

Search every one of these corporate Twitter profiles from the duration of the Ferguson protests, and you’ll find absolutely nothing. Every company with a statement out now — Sony, Microsoft, Bungie, Activision Blizzard, Ubisoft, EA, Nintendo — was absolutely silent six years ago.

Instead, corporate accounts from the time promoted upcoming games like Far Cry 4 with darkly ironic blog posts about wanting a “politically unstable” setting with “a history of conflict” … a “failed state,” in the words of producer Alex Hutchinson. Companies that paid a little bit of attention to the world around them participated in the ice bucket challenge for ALS awareness that had gone viral the previous month, arriving late to the party and offering corny contributions of their own.

And then the marketing campaign for Battlefield Hardline began in earnest that August, a game that took a military first-person shooter and re-skinned it with a coat of cop paint. Hardline is perhaps the high-water mark of video game cluelessness: a game made possible because the militarization of police in the United States is blindingly obvious. But since video games are so beholden to power fantasy, the only nuance Hardline offers is the option to “arrest” “perps” (often by striking them unconscious) or kill them.

[embedded content]

In big-budget video games, the real world is merely source material, a dry list of things that happened somewhere else, some time ago, to somebody else. Rare is the game interested in what is happening now; rarer still is the video game publisher or studio openly concerned with the state of the world. When the industry is forced to acknowledge tragedy, it often does so with weak concessions. In 2017, the Pulse nightclub shooting, which occurred days before E3, the biggest trade show of the year, was either ignored or met with moments of silence or short statements of support — right before diving into presentations often full of video game gun violence. When three people died in a mass shooting during a Jacksonville Madden tournament, the lack of security at gaming events came under scrutiny, as an industry that loves giving lip-service to its community failed to do its due diligence in a material way.

It is telling that the developers of Call of Duty have only just now pledged to do something about racism in its player base, after years of complaints from its community.

Acknowledging the necessity of action in response to the protests against anti-black racism and police brutality in this country right now means contradicting decades of careful messaging on the part of game publishers and studios designed to do just the opposite. It’s abject cowardice in the service of capitalism, where a white supremacist’s dollar is just as good as yours or mine.

The bar set by its competitors seems sufficiently low, and this does not attempt to clear it

No corporation should be applauded for making a statement or even a donation. Actions like these are not a measure of the moral character of billion-dollar companies; they’re another form of negotiation under capitalism. Every company that has a game it wants you to play is now measuring your tolerance for silence or inaction the way they measure where to line-step with the implementation of loot boxes. The public, lacking the luxury of ignoring the real world around them, does not have to accept these minimal gestures as sufficient.

Is Rockstar Games’ decision to shut down servers for two hours with no substantial commitment to doing anything else enough for you? The bar set by its competitors seems sufficiently low, and this does not attempt to clear it. Video game companies, an industry uniquely sensitive to the “passion” of entitled fans, are often more than happy to listen to a vocal minority. So they can do some more listening, if they’re made to.

Progress is infuriatingly slow and frustratingly incremental. The wheels of management, governed by wealth and whiteness, do not turn for the sake of black employees or audiences. It took nearly six years and a second eruption of public indignation over the murder of black people by law enforcement to move to where we are now, where every major company and publication that covers them is finally having the same conversation as the public.

And still, video games lag behind the rest of the world. Ben & Jerry’s, the ice cream brand, was downright speedy in comparison, releasing a forceful, thorough statement on the Tuesday after protests began. Lego, of all companies, has set one of the strongest examples, donating $4 million and suspending advertising of all its police-themed sets. Video games want to know what you’ll settle for. It’s an industry that loves trumpeting its astonishing revenue and importance to the culture, where a single free-to-play hit can make nearly $2 billion in profits, and is frequently positioned as a balm for troubled times. They should act like the cultural force they claim to be.