Fat Bear Week isn’t until October.

Yet the brown bears of Katmai National Park and Preserve — who are livestreamed on the explore.org webcams over the summer — are fattening up well before their looming winter hibernation. The reason why is an extraordinary 2020 sockeye salmon run, which will soon eclipse the record for fish swimming up the major waterway (the Naknek River) that ultimately leads to Katmai’s famous Brooks River, where the bears feast. Reliable observations go back to 1963.

“All indications are that we’re going to set a new record,” Curry Cunningham, a fisheries ecologist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks who researches salmon runs in Bristol Bay, told Mashable. The record for sockeye salmon swimming up the Naknek River, is around 3.5 million salmon, set in 1991. As of July 13, more than 3.4 million sockeye had already swam up the river.

Over the past week, bear cam viewers and Katmai rangers have watched hordes of salmon leap above the water as they attempt to surmount the Brooks River waterfall.

“The run this year is just exceptional,” Mike Fitz, the resident naturalist for explore.org and a former park ranger at Katmai, told Mashable. There have generally been bounties of fish at the falls since late June, Fitz said.

And that means fat bears.

“The bears right now are the beneficiary of tons of salmon,” noted Fitz. “The bears are extremely fat for this time of year.”

Of course, the bears aren’t nearly as fat as they’ll be in September, after months of chomping on calorie-rich salmon. For reference, take last year’s Fat Bear Week champion, Holly.

A number of important factors have contributed to the large salmon runs in recent years in Alaska’s Bristol Bay, which feeds the Katmai region.

The salmon have large swathes of protected land, like Katmai, where they can breed and flourish. “These are intact ecosystems with very little human development,” said Cunningham. There are no dams in Katmai impeding fish from reaching their habitats, and there are no industrial sites polluting the water.

However, the Trump administration is weighing the construction of an unprecedented copper and gold mine in the region, replete with water treatment plants to discharge mine water into streams, a 188-mile-long natural gas pipeline to power the mine, pits for mud-like mining waste (known as tailings), roadways for trucking, and a brand new port to unload mined materials onto ships.

“The bears are extremely fat for this time of year.”

“It’s talking about turning a large part of Alaska into an industrial mining district,” Alaskan bear-viewing guide Drew Hamilton, who is the former assistant manager of Alaska’s bear-filled McNeil River State Game Sanctuary and Refuge, told Mashable last year. Ecologists, biologists, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have concluded the mine would adversely and substantially impact the Bristol Bay fishery. (The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers will release a critical environmental review of the potential mine next week, on July 24.)

Overall, the Bristol Bay watershed, with a diversity of large rivers, is seeing plentiful salmon numbers this year, though not every river itself is having a strong, productive year. That’s the benefit of conserving such a vast expanse of land and natural resources: The overall system is robust, even if certain rivers naturally see a diminished run of fish during some years.

“As a whole, our production is maximized,” said Cunningham. “As long as all [rivers] can thrive, you do better overall.”

What’s more, the Bristol Bay fishery is well-managed, explained Cunningham. This means the state of Alaska ensures a sustainable number of fish swim up the river (called an “escapement”) every year. The fishing industry can’t overexploit fish in Bristol Bay. As a result, wild fish still flourish in Katmai, while supporting a giant Alaskan industry. In Bristol Bay, for example, over 41 million sockeye salmon were caught in 2018.

“There’s enough fish for people and there’s enough fish for wildlife,” said Fitz. “There’s plenty for everyone right now. That underscores the health of this area.”

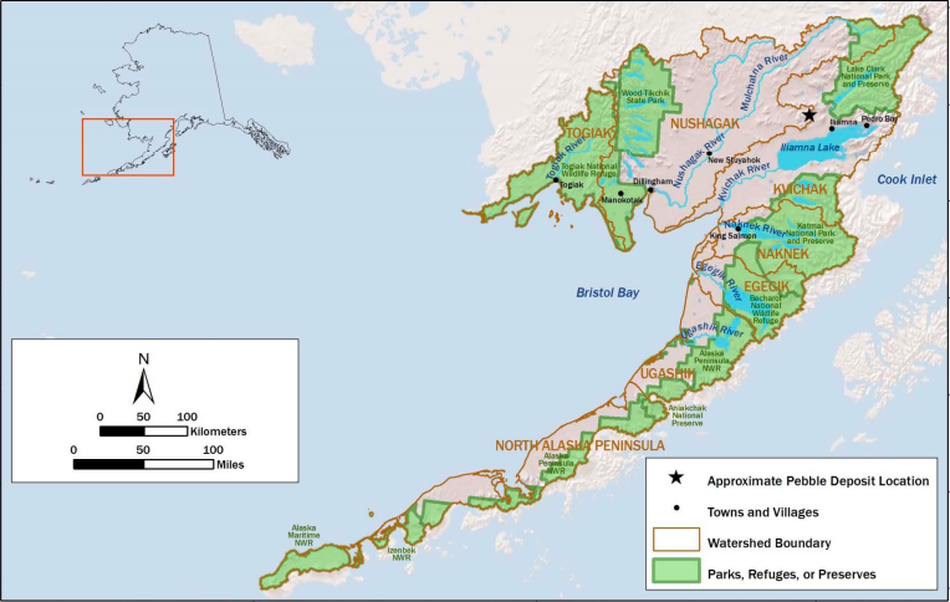

The Bristol Bay watershed.

Image: epa

Yet, relentlessly warming oceans and climate change may threaten Alaska’s sockeye salmon, a cold-water species, in the future. The threats already loom large for more southern-dwelling salmon species in the Pacific Northwest and California. This includes rivers that become too warm for fish to successfully reproduce, changing ocean currents, and marine heat waves.

So far, the Bristol Bay sockeye salmon have largely avoided these threats because they live in a colder portion of their habitat, noted Cunningham. It’s inevitable, however, that the oceans will continue to warm up this century, as the seas soak up over 90 percent of the heat trapped on Earth by humanity.

“Global warming is really ocean warming,” NASA oceanographer Josh Willis told Mashable last year. Ocean warming, of course, can be limited if society ambitiously decarbonizes over the coming decades.

For now, the Katmai ecosystem is thriving. It’s evident in a Brooks River teeming with leaping salmon, and fat bears.

“The bears are very healthy overall,” said Fitz. “They get their fill quickly.”