A man’s mind is filled with glorious, reality-altering visions — images that he feels compelled to bring to life. When he does, the constant thrum of his imagination is quieted, only to be replaced by a new, constant gnaw of guilt. That sounds a lot like the story of Oppenheimer, doesn’t it?

Christopher Nolan‘s ambitious, three-hour epic about the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy), the father of the atom bomb, is a fascinating and frequently horrifying dive into the mind of one of history’s most important men. It’s a study of not only the cost of dreams, but also the complex nature of guilt. Are you allowed, for instance, to feel guilty about the consequences of your own actions when the consequences are obvious from the very beginning to everyone, including you? As compelling as it is, Oppenheimer isn’t the first film to explore such issues.

Famed animator Hayao Miyazaki delivered his own exploration of the value and price of dreams when he made The Wind Rises. Released in the U.S. 10 years ago this week, the film is a fictional drama based on the life of Jiro Horikoshi, whose lifelong aeronautical dreams manifested themselves as fighter pilots used by the Empire of Japan throughout World War II. Like Oppenheimer, the film was criticized at the time of its release for not exploring the fallout of its protagonist’s actions as deeply as some would have liked. Repeat viewings of The Wind Rises reveal, however, that Miyazaki is fully aware of the death and destruction his protagonist’s actions wrought. He also remains in awe of Horikoshi’s artistry — and that tension is what makes The Wind Rises one of the greatest animated films of the 21st century.

The Wind Rises begins fittingly in a dream. In it, a young Jiro Horikoshi flies in a plane through the Japanese countryside only for his flight to be interrupted by the emergence of a war zeppelin carrying breathing, gulping bombs that tear his plane apart and send him free-falling to the ground. These opening minutes illustrate the beauty of both flight and the pursuit of it, as well as how magnificent crafts like airplanes are always, inevitably used as a means of violence.

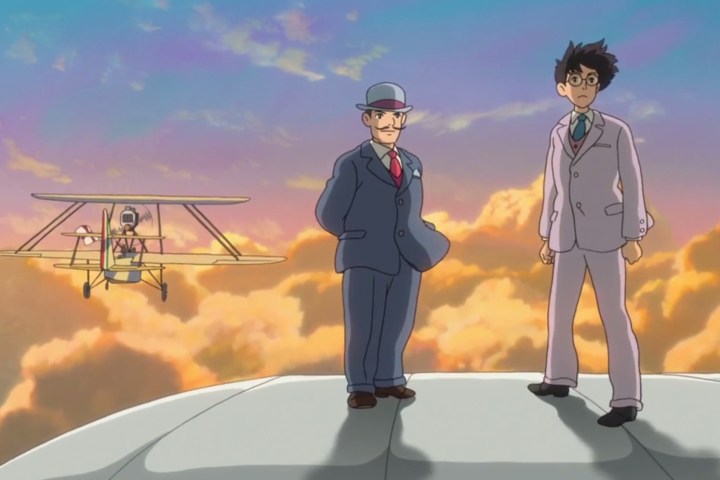

Visions of war and death permeate The Wind Rises. Miyazaki fills the film with images of burning planes and fields. In one early dream, a still-young Jiro meets his idol, Italian aircraft designer Giovanni Battista Caproni, and the two look on in wonder as dozens of the latter’s planes soar through the sky. “Look at them. They will bomb an enemy city. Most of them won’t return,” Caproni announces, prompting a sudden cut to a shot of planes falling over a torched city — the flames of which remain in the reflection of young Jiro’s glasses in the image that immediately follows. “Airplanes are not tools for war. They are not for making money,” Caproni tells Jiro. “Airplanes are beautiful dreams.”

He’s right and he’s wrong, and so is Jiro’s friend and fellow aircraft designer Kiro Honjo,when he remarks, “We’re not arms merchants. We just want to build good aircraft.” His comment immediately follows images of his own WWII bombers flying over burning cities and getting shot out of the sky. When Jiro asks who Kiro’s bombers will fight, his friend responds, “China. Russia. Britain. The Netherlands. America.” These details reveal the falseness of Kiro’s assertion about his and Jiro’s roles in the world. They may not be arms merchants, but they are in an arms race.

As he strives to bring the aircrafts of his dreams to life, Jiro travels to the Weimar Republic to research German engineering techniques and spends one summer at a retreat in the Japanese town of Karuizawa. Miyazaki, for his part, frequently references the fascism of Jiro’s time and even goes so far as to directly acknowledge the Nazis’ growing presence throughout Europe. While at his summer retreat, Jiro also falls in love with Nahoko Satomi, a young woman sick with tuberculosis. The two quickly become engaged and, years later, marry.

Jiro’s sister warns him that Nahoko’s illness will doom their marriage to be short-lived, but he marries her anyway. He puts their love above their relationship’s tragic outcome, the same way he puts the beauty of his airplanes above the horrifying ways they will be used. After he has finally designed his dream plane, though, Jiro is distracted from its successful test flight by an omen of death — a gust of wind that informs him of Nahoko’s passing.

Later, in a subsequent dream, Caproni amends part of his previous statement. “Airplanes are beautiful dreams,” he reiterates before adding, “Cursed dreams, waiting for the sky to swallow them up.” Earlier in the film, he argued that the world is better off with beautiful things like airplanes and pyramids — even if they might be used for evil. The Wind Rises neither endorses nor refutes that sentiment, but it does make it clear that Jiro has been irrevocably changed by what has become of all of his dreams, and Miyazaki goes out of his way to highlight both the horror and majesty of his protagonist’s work.

Obviously, America’s use of nuclear warfare on Japan in 1945 makes linking The Wind Rises, a film by Japan’s most revered animator, and Oppenheimer, an American-funded blockbuster from a British filmmaker, a difficult and complicated act. Make no mistake about it: The gravity of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s sins greatly outweighs those of even Jiro Horikoshi. In the two men, though, Nolan and Miyazaki find similar stories — modern tragedies about the complicated nature of pursuing one’s dreams in a world that is prone to using its inventions for their ugliest possible purposes. The line between a dream and a nightmare can be all too easily blurred and crossed, and that’s apparent in both Oppenheimer and The Wind Rises.

At the end of the latter film, Jiro returns to the same dreamscape he met Caproni in previously, but it’s different than it was before. Its endless fields of blowing grass have become littered with the metal carcasses of destroyed airplanes. Jiro eventually finds Caproni standing again at the top of a hill. “This is where we first met,” he remarks. Caproni calls it their “kingdom of dreams.” Jiro responds, “Or the land of the dead.” Which is it? A place of beauty and imagination, or a graveyard? Is one destined to become the other with enough time?

Maybe life is simply learning to accept that beauty and horror can — and often do — exist side by side. Maybe all that matters is how we grapple with that fact. In Oppenheimer, the horrors its lead character has facilitated freeze him in a perpetual cycle of guilt and self-flagellation. In The Wind Rises, Jiro decides to live in spite of all that he’s done and lost. One film believes in the irrepressible weight of guilt, the other in the importance of carrying on. And it’s ultimately the ideas it shares with — as well as the ways in which it diverges from — Oppenheimer that make The Wind Rises not only a fascinating programming partner to its 2023 successor, but also a powerful counter to it. Ten years after its release, its beauty and importance only continue to grow.

The Wind Rises is streaming on Max. Oppenheimer is streaming on Peacock.

Editors’ Recommendations

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews