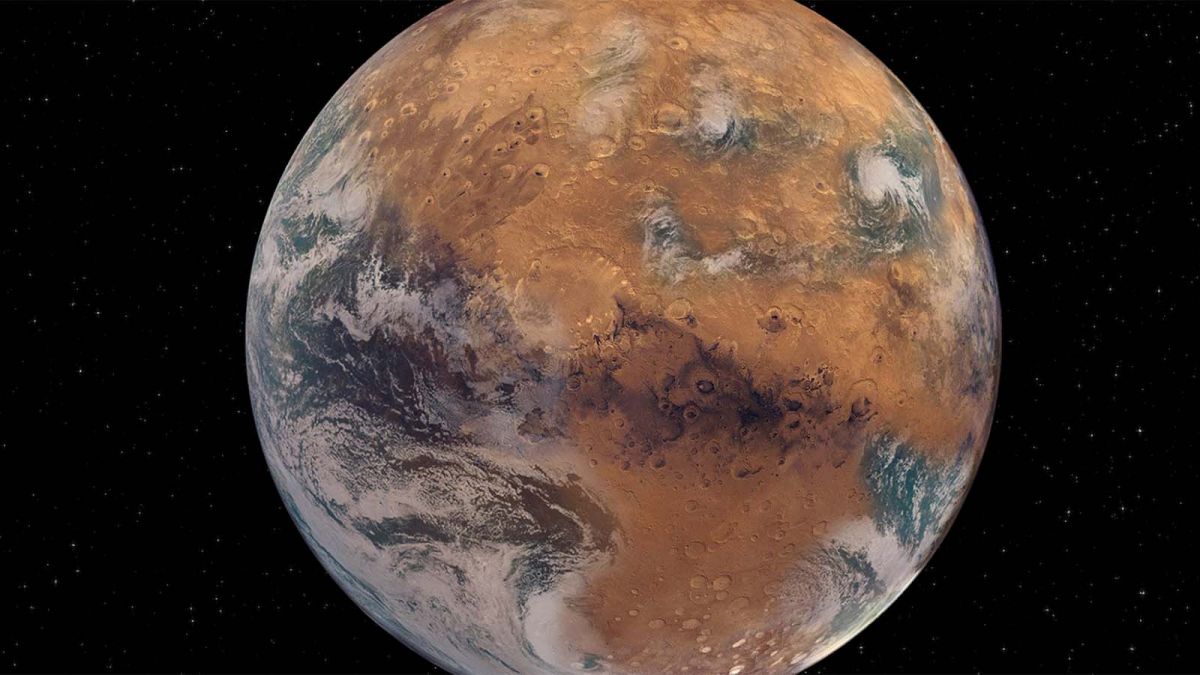

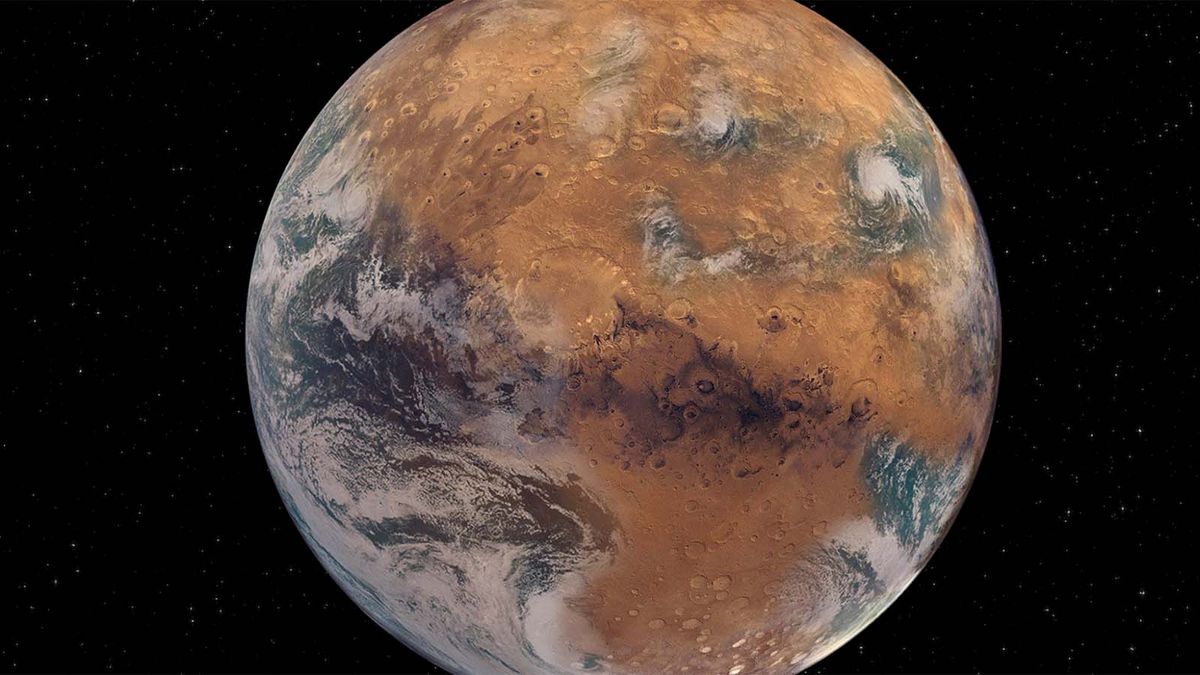

Many satellite and robotic expeditions to Mars have documented the Red Planet’s many river valleys, lake beds, and flood channels, revealing a landscape carved by an ancient and active water cycle. But today, Mars is as dry as a bone, and if a new study is correct, the size of the planet itself might be to blame.

“Mars’ fate was decided from the beginning,” assistant professor of earth and planetary sciences at Washington University in St. Louis Kun Wang said in a statement. “There is likely a threshold on the size requirements of rocky planets to retain enough water to enable habitability and plate tectonics, with mass exceeding that of Mars.”

Wang, the senior author of a new study led by graduate student Zhen Tian and published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, examined stable isotopes of potassium in various meteorites whose origins are known to approximate the presence, levels, and distribution of volatiles that can be a tracer of sorts for the amount of water present.

By analyzing Earth’s composition along with meteorites from Mars, the moon, and the asteroid 4-Vesta, the study’s authors found a well-correlated relationship between a body’s size and its abundance of this specific potassium isotope.

Additionally, the 20 Mars meteorites – ranging from 200 million years old to 4 billion years old – revealed that Mars lost its volatiles, including water, at a much faster rate than Earth did in the first billion years of its formation.

“The finding of the correlation of [potassium] isotopic compositions with planet gravity is a novel discovery with important quantitative implications for when and how the differentiated planets received and lost their volatiles,” said study co-author Katharina Lodders, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at Washington University at St. Louis.

Mars in its early formation would have been remarkably similar to Earth according to some models, including a thick, Earth-like atmosphere and standing water on its surface.

How much water is up for debate, but what isn’t is that somewhere along the way, as our colleagues over at Space.com explain, Mars lost its protective magnetic field and the ravages of the solar winds stripped away much of its atmosphere and evaporated all of its water about a billion years after it formed.

Analysis: what does this mean for the search for alien life?

The new study offers an important insight into the search for extraterrestrial life. While we have found thousands of exoplanets orbiting around alien stars, determining which ones are good candidates to host life presents a challenge.

Studying them all is currently impractical and many can be ruled out by some of the data we already know. We can largely rule out planets that do not orbit within the star’s “habitable zone”, the theoretical band around the star where liquid water can exist on the surface of a planetary body. But both Venus and Mars exist within the habitable zone of our sun, and both are currently inhospitable to life.

“This study emphasizes that there is a very limited size range for planets to have just enough but not too much water to develop a habitable surface environment,” Klaus Mezger, of the Center for Space and Habitability at the University of Bern, Switzerland, a co-author of the study, said. “These results will guide astronomers in their search for habitable exoplanets in other solar systems.”

This new study could add another important filter on our exoplanet data to help narrow down possible candidates for study, Wang said.

“The size of an exoplanet is one of the parameters that is easiest to determine. Based on size and mass, we now know whether an exoplanet is a candidate for life, because a first-order determining factor for volatile retention is size.”