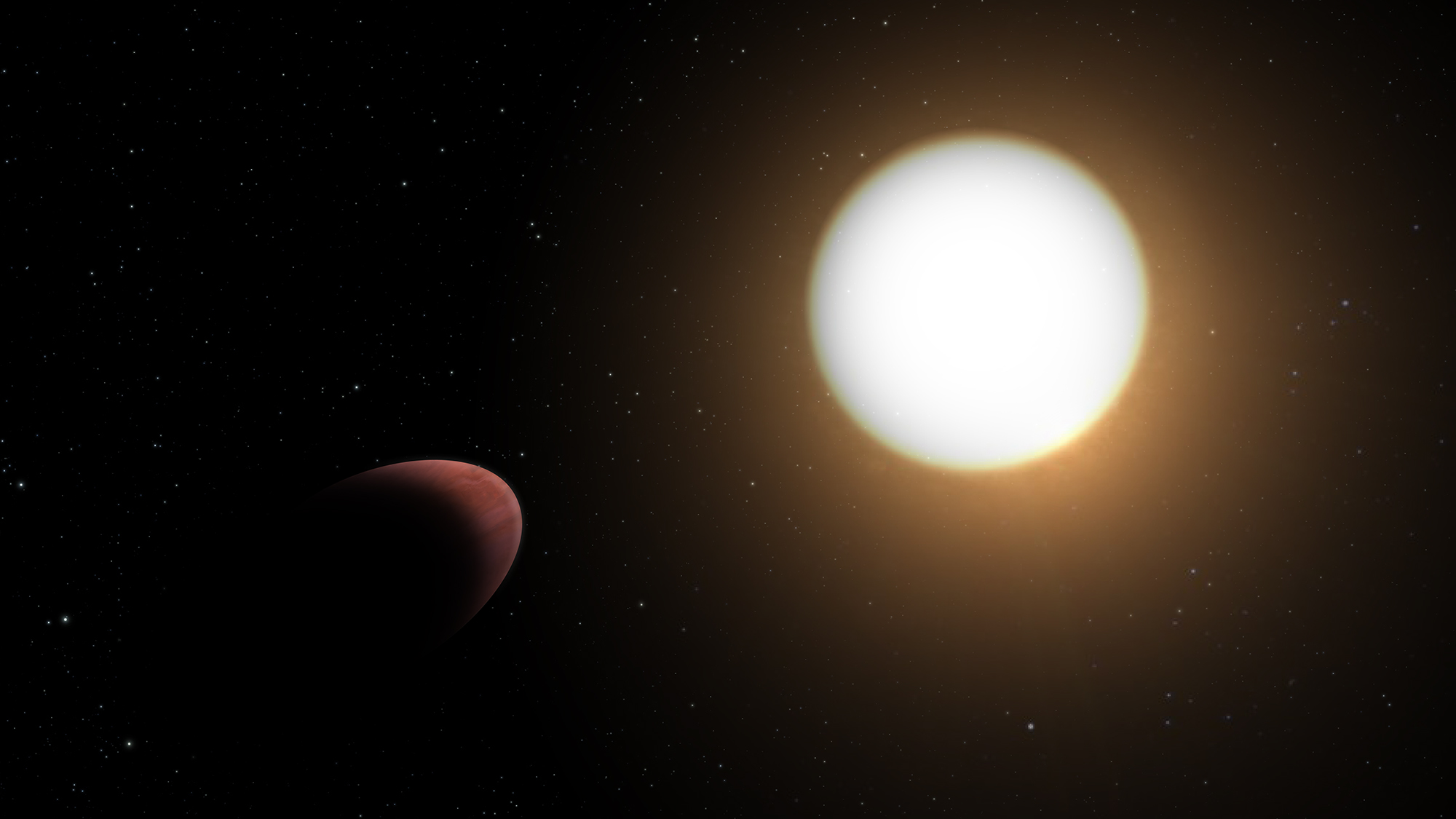

Planets are typically round bodies in space that orbit stars, at least most of the time anyway: We’ve just gotten our first look at an exoplanet that has been deformed by its star’s gravity into a rugby ball-like body.

While it sounds weird as heck, this isn’t unexpected — but it is the first time we’ve ever actually seen something like this out in the universe. The exoplanet, detected by the ESA’s Cheops exoplanet-hunting mission, orbits WASP-103 in the constellation Hercules.

Cheops finds exoplanets by measuring the light of stars and watching for telltale dips in luminosity when a possible exoplanet passes between us and the star. Dips that come at regular, precise intervals are very strong evidence of an exoplanet.

This exoplanet, WASP-103b, is a gas giant about twice the size of Jupiter with 1.5 times its mass. But rather than orbiting out in the farther reaches of its solar system, WASP-103b is what’s known as a “hot Jupiter”.

These are gas giants that orbit extremely close to their star, often much closer than even Mercury orbits our Sun. As a result, these exoplanets typically orbit their stars much faster than we’re used to seeing, but WASP-103b completes an orbit around its star – which is about 1.7 times larger than our sun – in less than a day.

That puts it extremely close to WASP-103; so close, in fact, that the gravity exerted on the star-facing side of the planet is much greater than that exerted on the side facing away from the star.

This difference in gravity, known as tidal force, is stretching the exoplanet out of the typical spheroid shape. We experience something similar with the moon as it produces ocean tides on Earth, hence the name. Until now though, we’ve never seen these forces actually deform a planet.

The Cheops astronomers managed to detect the deformation thanks to the exoplanet’s very rapid orbital period. This gave astronomers plenty of opportunities to take measurements and observe the exoplanet transiting the star, and the data they were seeing in the light curve of the star revealed the planet’s unusual shape.

“It’s incredible that Cheops was actually able to reveal this tiny deformation,” Jacques Laskar, of the Paris Observatory, Université Paris Sciences et Lettres, and co-author of the study detailing the findings in this week’s Astronomy & Astrophysics journal, said in an ESA statement.

“This is the first time such analysis has been made, and we can hope that observing over a longer time interval will strengthen this observation and lead to better knowledge of the planet’s internal structure.”

Analysis: why didn’t our own Jupiter become ‘hot’?

When we first started looking at exoplanets, we expected to see them arranged like they are here in our own solar system, with rocky inner worlds and large gas giants in the outer regions.

We’ve found a startling number of hot Jupiters though, including the very first exoplanet ever identified around a main-sequence star (i.e., one that wasn’t a stellar corpse), Pegasi 51b.

While a majority of gas giant exoplanets we’ve identified reflect the setup of our own solar system, it does beg the question of what causes a gas giant to quickly migrate into such a close orbit around a star, and what kept the original Jupiter from doing the same.

We don’t really know, honestly. That’s one of the reasons astronomers are so keen to study exoplanets – it’s our best real hope of understanding how our own solar system formed.