Toward the end of 2021, I was one of the countless tech workers who left one job and took another. The process surprised me in a number of ways. I needed to update my priors about a few things, and by writing this, maybe I’ll update yours, too.

First, I thought it would be easy. My reasoning was as follows:

- I know how hard it is to hire great developers

- I know I’m a good developer…

- Everyone’s desperate to fill roles…

- So it should be a walk in the park.

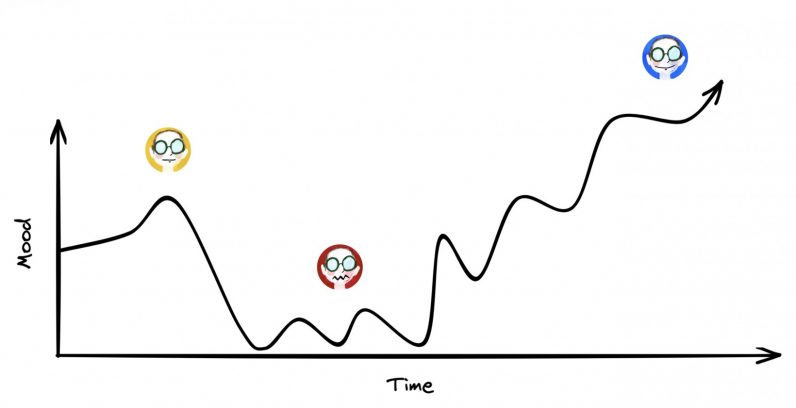

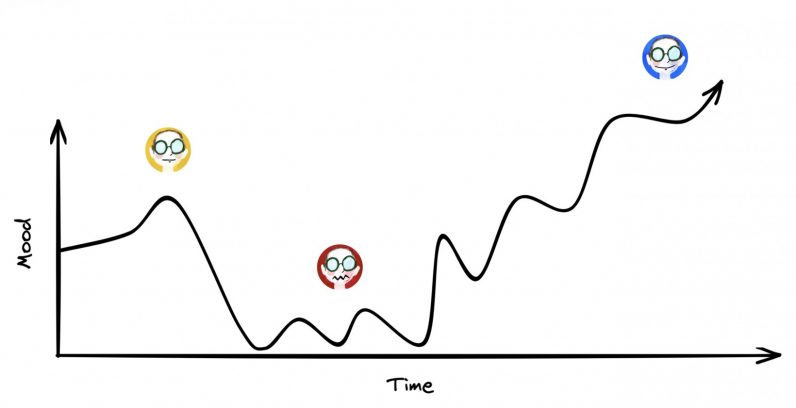

It turns out it wasn’t. It wasn’t radically hard, but it required significant thought and energy. In the middle of the search, I got kind of pessimistic… And yet, in the end, it was successful both in terms of the total number of offers received and their dollar values.

I’ve tried to capture some of my learnings in a form that may be useful to you. Take everything I say with a grain of salt.

Everyone’s experience is their own, and this may not apply to you. Also the TTL on any post like this is probably pretty short.

1. Understand that the system is overloaded

We said that 2020 was the year that broke every time-series chart and 2021 said “hold my beer.” Everything’s overloaded, and the job search infrastructure is no exception. In-house recruiters I spoke with had hoarse voices, were late to meetings, and occasionally confused me with other candidates. And I don’t blame them. They are dealing with unprecedented pressure from their employers, while at the same time they have more applications than they can process.

It’s almost like a Retry Storm. Companies are overloaded with applicants, which ends up in a subpar experience. Employer latency causes applicants to freak out and put out more applications, recursively exacerbating the problem.

My advice:

- Take a deep breath. You’ll feel compelled to draw conclusions based on incomplete information, choose not to. Silence from companies can be harder to deal with than rejection because it begs us to read into tea leaves. Just pause. Conclusions will come in time.

- Recruiters are tired, give them some grace. They’re trying. Some of them are new on the job themselves. Others just had their coworkers quit. Try not to take it personally.

- It’s ok to politely check in. As with all things, there’s the right timing and dosage.

Be gracious in cases of rejection. It doesn’t matter how great you are, you’re not a good fit everywhere. And even when you are, misreads happen. Maybe they’re making a mistake, or maybe they’re saving you from one. There are more fish in the sea.

2. Network

I’ve heard it said that most jobs are filled through networking… I don’t know if that’s been rigorously established, but it’s the kind of statement that just feels true. When I started my search, I decided that I didn’t want to rely solely on my existing contacts for introductions because I didn’t want to limit myself to my known universe. I wanted to branch out. Broadly speaking this was a waste of my time. Most of the companies that I applied to without a contact never wrote me back, or wrote back too late for me to want to take the conversation further.

I expected networking to be effective, but I was surprised by the degree. Given how overloaded the system is, networks allow you to punch through the noise and get in front of the right people. I wouldn’t disregard conventional wisdom on this one. Use the networks you have.

3. Learn from your cover letters

I was surprised by how many cover letters I had to write, even with a warm introduction. I knew they wouldn’t be read closely, but it required non-negligible attention from me. I didn’t want my cover letters to stand out in a negative way.

I observed a lot of variance in the effort required for me to write a cover letter. Sometimes an articulate and crisp cover letter just fell out of my mind. Other times it was like pulling teeth.

I started recording the subjective effort required to write a cover letter. I realized that the ease with which I wrote a cover letter, indicated if the company would be a good fit. If I couldn’t articulate in a cover letter why a company was right for me, maybe that’s a sign that I’d struggle during an interview. Maybe it’s a sign that it’d be hard to tell my friends and family about the company if I do get hired. Maybe it’s a bad fit.

Like with all metrics, it’s imperfect! But it’s something.

4. Take-homes

Take-home projects don’t seem to be quite as ubiquitous as they were a few years ago, but I still had to do quite a few of them.

Often it only takes a couple of hours to meet the bare minimum requirements, but it requires significantly more effort to stand out. This presents some unfortunate systemic biases. For example, if you spend a lot of time taking care of a family member, and are doing a job search while working full-time, it’s extremely difficult to find the time or energy to do take-home work well.

A couple of companies paid me to do a take-home assessment, which I appreciated. I took it as a signal that they valued my time investment.

Even though the system is pretty unfair and imperfect, I have some pointers for how you can stand out in take-homes that I think are worth sharing.

5. Pick something to nerd out on

Looking for a way to go above and beyond? Pick some aspect of the problem and take it to the next level.

Maybe you’re being asked to write a program that reads ‘stdin’, does some processing, and writes to ‘stdout’. It’d be trivial to do the work in memory, but you could decide that you want to stream the input and output so that your program supports arbitrarily large input sizes.

Maybe you decide you want to go a step further and load test it. Perhaps you can cover an edge case in an interesting way?

I found that take-homes often fell into one of a few buckets:

- Data processing script

- UI

- Fullstack app

When you do one, you can start to borrow little flourishes from one and use them on others. The problems are different enough that you can’t copy meaningful code, but you can absolutely borrow structure, testing techniques, and sparkles from one project to another.

6. Have a good readme

Spend more time than you think on a readme. It may seem ridiculous to document a silly sample project, but it will show that you care about the job you’re applying to and demonstrate an ability to write for humans.

Talk about what you did, how to run it, and what went into your design decisions. If you’re being asked to build a UI, include screenshots–many of the people reviewing your code won’t have the time to fire it up. For non-UI take-homes, include sample output. The point is that you want someone who only sees the readme to understand that you did a good, careful job.

7. Use diagrams

Take-homes offer an opportunity to show how you think and communicate visually.

I used Monodraw to create ascii art diagrams in my code and my readme. I got a lot of comments about it from interviewers.

Absolutely love using @Monodraw to document my code pic.twitter.com/kj2pImmW3b

— Zeke Nierenberg (@_off_by_one) August 5, 2021

Other nice diagramming tools could be Mermaid or Excalidraw (I love Excalidraw).

8. Have tests

Write automated tests. I believe that most companies will feel that a lack of tests reflects poorly on a candidate. Focus on tests that are readable and help them understand how you think about the problem space. Great tests read like documentation.

9. Validate inputs

Good software validates inputs at its perimeter. Sometimes companies will throw test data at your code that they didn’t share with you. If there are errors, that’s not always a bad thing, but they should be semantic and sensible. You should codify the assumptions you’re making not just with tests, but with input validation.

10. Use modern tech

Don’t pull out old libraries and tools. Use the new stuff. That may seem intimidating if you aren’t familiar with the latest tooling. Just pick tools that are modern and minimalist, of which there are many. These tools are also easier to read and understand if the interviewer also doesn’t know them. It’s worth the small time investment to find a cool new library rather than pulling out the same one you used on your last job search.

11. Salary negotiation

I’m not an expert in salary negotiation. I’ll still share the general framework I used.

“What are your expectations for salary?”

Many companies asked me about my salary expectations. I said something like this:

Look, this is an unusual time. I’m actually not sure what a fair market rate is for me. I’ve heard of people with similar experience being offered between X and Y, and so I expect I’ll get offers in that range.

Some companies just took that information. Others expressed concern because they knew they could not make offers in the high end of my range. In response, I told them that I wasn’t sure I’d be getting offers that high, and that my range was intentionally large. I also told them that base salary was not the only thing that I cared about and that I would be making a nuanced decision based on many factors.

12. Lining up offer timelines

At the beginning of the hiring process, I picked a date at which point I was hoping to conclude it. Whenever I had initial conversations with companies I told them this date. Because companies got back to me at different times, sometimes this added a little bit too much pressure, and I ended up withdrawing from the process with some.

After each stage of interview, I tried to refine my understanding of when I might be receiving an offer. Once I knew might be getting an offer from a company, I told other companies about it. I said something like:

Hey [first-name]!

I wanted to let you know that I’m expecting (🤞) to get an offer from another company in the middle of next week. I’ve really enjoyed the process with [your-company] so far, and if it doesn’t work out, I would hate for interview logistics to be the reason why. I know I said I was looking to make a final decision by x, but do you think it would be possible to move that up a little bit? Maybe we could conclude the process by y? If this just isn’t logistically possible, I totally get it, and I’ll do what I can to make things line up. I’d really appreciate it!

This approach worked every time and was 100% truthful. I would not recommend doing something like this if you’re not expecting an offer just to create FOMO.

13. Comparing offers

This is genuinely hard because predicting the future is hard. All the companies I got offers from seemed compelling in one way or another.

I tried to assign a monetary value to everything in a spreadsheet. I quantified uncertainty (bonus, stock performance, etc) as best I could. It was abundantly clear which offer had the highest dollar value.

I then asked myself, “do I like any of the other companies enough to pay $[amount] to work there instead of [company]?” I framed it this way to myself because a dollar not earned is the same as a dollar spent.

After telling the other companies about the highest offer, and them not being able to meet it, I took the highest offer I got. That isn’t the right choice for everyone in every situation, but it was for me this time.

I’m a few months in, and so far I’m pretty happy! I didn’t feel like taking the highest offer was a sacrifice in any way. I wasn’t selling my soul. I felt good enough about all the companies and that gave me permission to make it mostly about money.

In summary

This is a great time to switch jobs if you’re feeling the itch. Companies are hungry for talent and you can absolutely do really well in a search. But, if your results will vary I think you’ll find that the outcome will mirror the effort you put in. In my case, it required some real heavy lifting.

Figure out where your effort can yield the best results and lean into it.

Try to learn about yourself in the process. You may end up with several offers, and there could be subtle cues from your application process that could come in handy. Journal, make spreadsheets, talk to friends.

Communicate openly and respectfully with the companies as the process progresses. Sometimes the truth is the best negotiation technique. Do what you can to make the truth work for you.

When it’s all said and done, take care of yourself. This process is exhausting. If you can, take a few weeks off.

This article from Off-by-one is a stream of thought about computers. The author, Zeke Nierenberg, writes about programming, education, tech-enabled thinking tools, and product development. Find the original article here.