If you’ve shopped for high-end headphones recently, there’s a pretty good chance you’ve come across something called the ‘Harman target curve,’ or perhaps just the ‘Harman curve.’ Maybe you read a review that said a pair of headphones sound amazing because they’ve been tuned to said target. Or perhaps you saw an edgy comment suggesting headphones tuned to the Harman curve suck.

But why exactly are more manufacturers, audiophiles, and reviewers paying attention to the Harman curve?

There is a lot of science behind the acoustics of headphones, much of it covered in our primer on speaker measurements, but in some ways, headphones are even more complex. This post isn’t intended to be an exhaustive guide to headphone measurements, but rather a primer to help you make a more educated purchasing decision.

Let’s dive in.

What the heck is the Harman curve?

The Harman curve is a science-backed frequency response target for headphones. It was created by Dr. Sean Olive and other researchers at Harman Audio in the 2010s (Harman is owned by Samsung and includes headphone makers like AKG and JBL) and is the result of several studies trying to pinpoint what makes a great-sounding headphone.

Basically, the Harman curve appears to be science’s current best answer to the question: “what frequency response is the most preferred for the most people?”

It’s worth noting that, as seen with frequency response measurements for speakers, what people ‘prefer’ is largely interchangeable with what people consider to be ‘neutral.’ People simply tend to like what sounds most natural to them.

I should also note that there are several versions of the Harman curve; the target changes depending on whether we’re talking about over-ear headphones or in-ear monitors(IEMs, AKA earbuds), for example. And again, the target has been tweaked slightly over the years with ongoing research.

What does the Harman Curve look like?

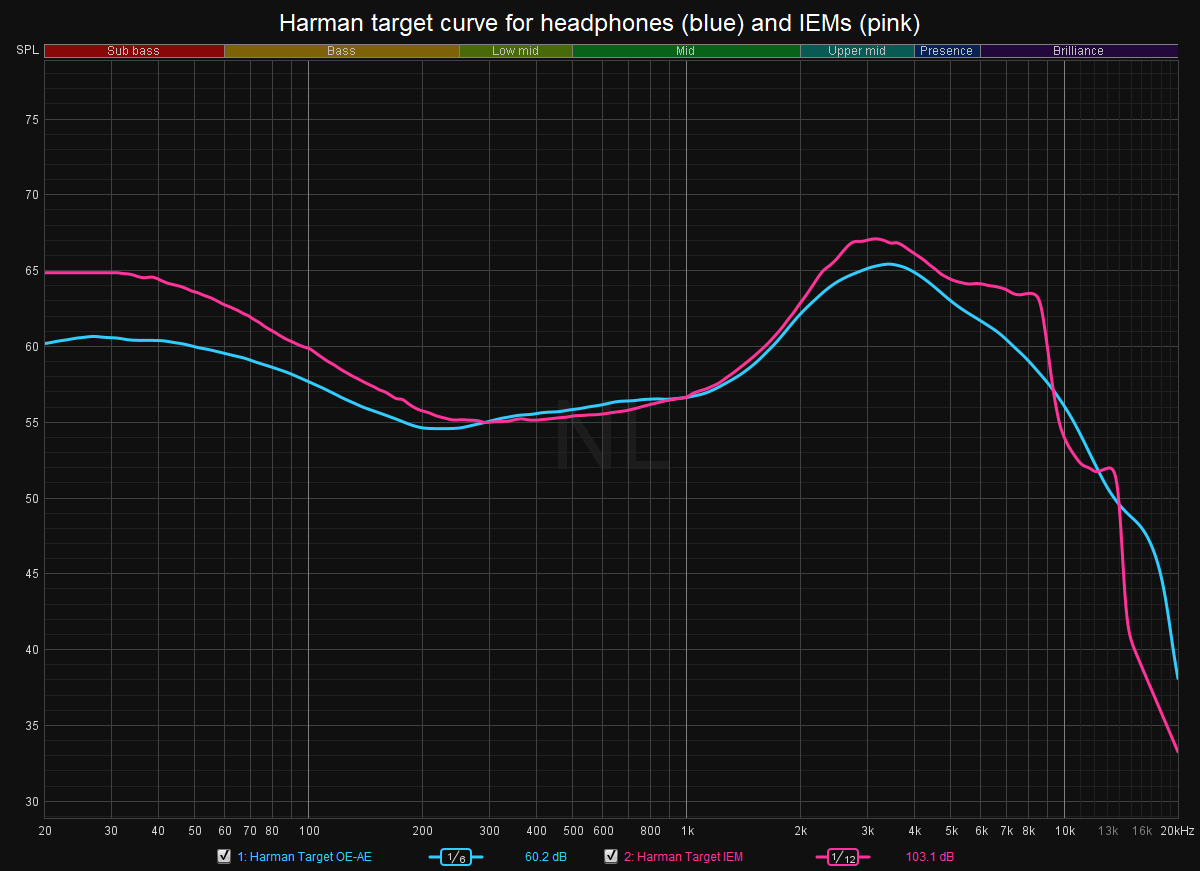

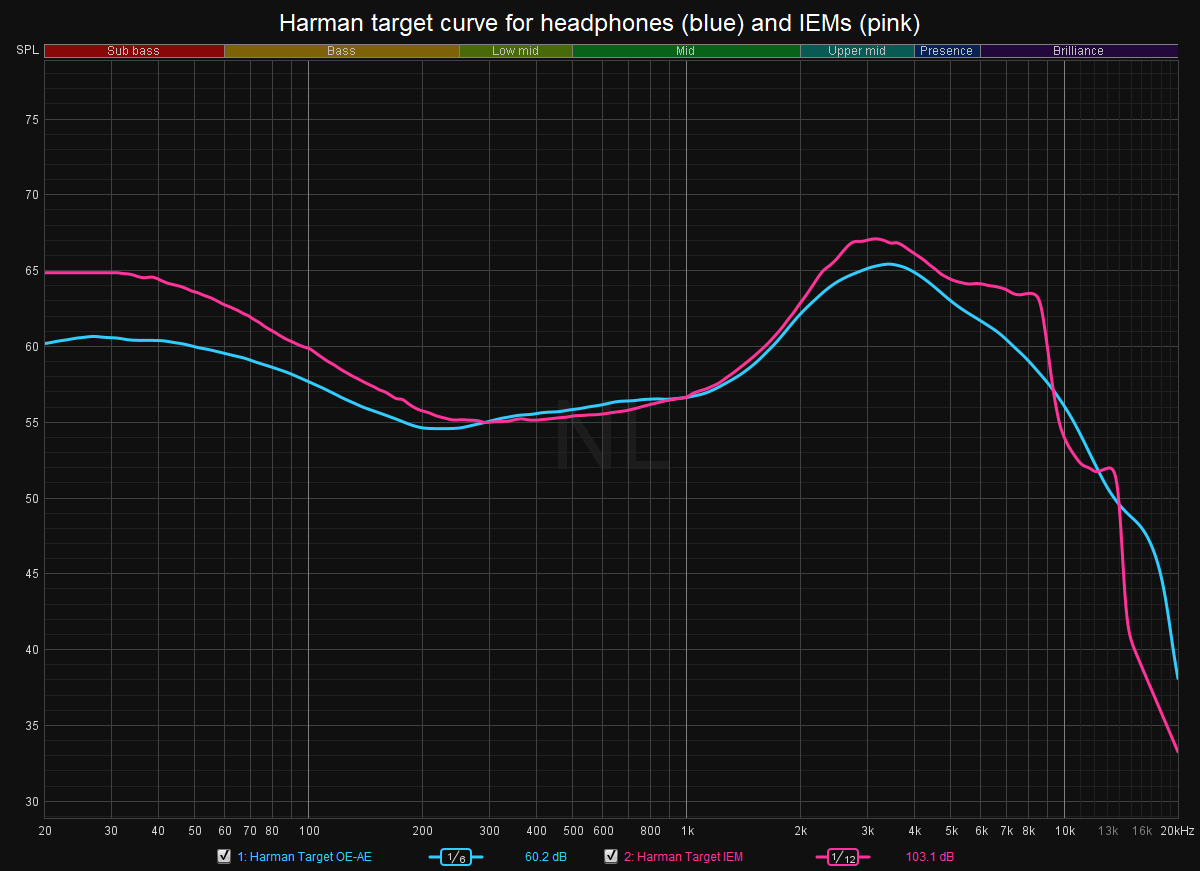

This is the latest version of the Harman curve for full-size headphones (blue) and IEMs:

Not that the above only applies to ‘raw’ headphone measurements without any particular calibration applied. It’s also the response as measured with the specific testing gear Harman uses – measurements created with other devices are not fully comparable.

That doesn’t look flat at all! How could that possibly sound neutral?

There is exhaustive evidence to suggest speakers which have a flat frequency response when measured in an anechoic chamber are preferred by listeners and perceived to be neutral. So why is the Harman target for headphones so far from a flat line?

The first part of the answer lies with our own bodies. When listening to speakers — or, you know, instruments and voices — much of the sound passes through your head and torso before arriving at your eardrums. Sound coming from the left speaker will pass through your noggin, causing its frequency response will change before it arrives at your right ear.

We call this modification of sound the head-related transfer function (HRTF). Our brains, clever things they are, use this modification of sound in order to figure out where sound is coming from.

The problem with headphones is that their proximity to your ear doesn’t allow for these frequency response changes to happen. Sounds leaving your headphones have a direct line of sight to your ear canals. So instead, it’s up to manufacturers to find a way to roughly emulate the HRTF in their headphones’ frequency response. Headphones with a truly flat frequency response will sound awfully dull.

But we also don’t just want headphones to replicate the sound of speakers in an anechoic room. Nobody listens to speakers in an anechoic chamber, after all (well, except for scientists). So the second part of the Harman curve is replicating some of the characteristics of an in-room speaker response.

When a good speaker is placed in a room, its sound develops a slight tilt, (more on why in our guide to speaker measurements) with more bass and less treble. The speaker is generally still perceived as neutral, but your brain uses that room tilt to help place the sounds leaving the speaker as existing in your room.

The scientists at Harman figured that since music is generally mixed to be listened to on speakers in a room, then ideal headphones would try to replicate the sound of good speakers in a room, leading to some of that big bass bump in the Harman curve.

The final curve was determined by responses from study participants, but the fundamental principle remains the same: the best headphones are the ones that sound the most like the best speakers.

But we all have different tastes in music! How can one frequency response fit all?

Here’s the thing: you’re probably a lot less special than you think.

The Harman research found that, as with speakers, the vast majority of people have similar tastes in headphones, and that preference can largely be predicted by frequency response data. In one study, researchers found that measurements could predict the preference for over-ear and on-ear headphones to a remarkable 86 percent accuracy. For in-ear monitors, the model was even more accurate, at 91 percent.

One study (Olive et al., 2014) tested listeners in different countries, age groups, and experience levels. Although participants gave different individual scores to different headphones — trained listeners tended to be more critical, for instance — they ranked headphones very similarly.

All that being said, person-to-person variations do exist. Older study participants as a whole tended to prefer brighter headphones due to hearing loss, while women tended to prefer a bit less treble energy. Some users preferred more or less bass. Different specific recordings might benefit from slightly different headphones, due to something called the circle of confusion. And we all have different heads and bodies with somewhat different HRTFs, making the perfect headphone for an individual listener hard to predict.

But these variations in preference tended to be much subtler than audiophiles often claim. Listeners tended to prefer Harman curve-tuned headphones despite individual differences, so it appears the overall contour of the Harman curve remains largely preferential over other tuning methods. Much of the variation in preference could be accounted for if headphones allow for quick bass and treble adjustments, enabling them to be flexible for an even wider variety of listeners and genres.

So is frequency response the only thing that matters?

There are certainly other things that will affect your listening experience.

If a headphone has excessive distortion or an intense resonance at a certain frequency, it might not sound great. It usually takes a massive amount of distortion for listeners to poorly rate a headphone, but it does happen.

Sometimes a headphone might track the Harman curve really closely but have a stray peak that you find really annoying. And the Harman curve doesn’t fully account for the spatial qualities of headphones, which vary depending on their size and design. Two headphones can have similar tonal balance, for instance, while demonstrating different spatial qualities.

Pure sound quality aside, there are certainly other important qualities to consider. Some people won’t buy headphones without noise-canceling, for instance, and many listeners consider comfort to be paramount. Other headphones might not get loud enough for your uses, and still others might have too much latency for your tastes. These quality-of-life characteristics are often just as important as sound quality.

Still, when it comes to tonal balance, frequency response is king.

So should I only buy Harman headphones?

Of course not.

Although the target curve as it’s currently known was developed by Harman, its headphones are far from the only ones to follow the target. Some headphone companies independently arrived at frequency responses that closely track the Harman target before it was developed, while others have since tweaked their headphones to match the curve.

Likewise, not all of Harman’s headphones match the curve, especially some of the companies’ older models.

I’ve heard Haman curve-tuned headphones and I didn’t like them! Now what?

Firstly, you should allow yourself at least a little time to adapt; if you’ve been listening to poorly tuned headphones for a long time, your ears may have a bit of acclimating to do.

But if that doesn’t help, that’s fine too. The Harman curve was never supposed to be the end-all-be-all for sound quality. Instead, it provides a starting point backed by science, which is a big step forward from the haphazard tuning many headphones had a couple of decades ago. Although most listeners are similar in their tastes, it’s possible the optimal headphone for you might vary somewhat from the Harman target.

Nonetheless, I’d still argue it’s important for any headphone enthusiast to have experience with a headphone tuned to the Harman curve because it is a useful reference.

The Harman curve is increasingly becoming an industry standard, so it provides a point of perspective for headphones that deviate from their sound. Say a review claims headphone A has less bass than headphone B, the latter of which follows the Harman curve. If you have experience with Harman-esque headphones, you’ll have a stronger understanding of the reviewer’s impressions and how they might relate to your own tastes.

Headphone acoustics is a field of continuing research, especially as binaural audio, Dolby Atmos, and other spatial audio techniques become more popular. We may find that the ideal headphone response continues to evolve over the next decade; some companies are looking to tailor headphones to the individual’s hearing, for instance.

But in the meantime, buying a pair of headphones tuned to the Harman curve doesn’t guarantee you’ll like them, but it’s simply your safest bet for getting something you’ll actually enjoy.