Compounds found in weed can make a species of roundworm hungrier, especially for their favorite foods, according to a new study that suggests the munchies aren’t just a human phenomenon. The fun discovery could actually help scientists someday better understand cannabinoids and their potential medical uses, the study authors say.

Cannabinoids are a large group of compounds found in cannabis. Though cannabidiol (CBD) and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) are the plant’s primary cannabinoids, scientists have discovered about 100 others. THC is known for causing the high that makes cannabis so appealing, but other cannabinoids seem to have more subtle effects. Humans and seemingly every other animal naturally produce their own version of these compounds, called endocannabinoids. These chemicals help regulate several aspects of our biology, from memory to pain sensation to hunger. Despite our ever-enduring interest in cannabis, though, there’s still a lot we don’t know about cannabinoids and how they work.

Advertisement

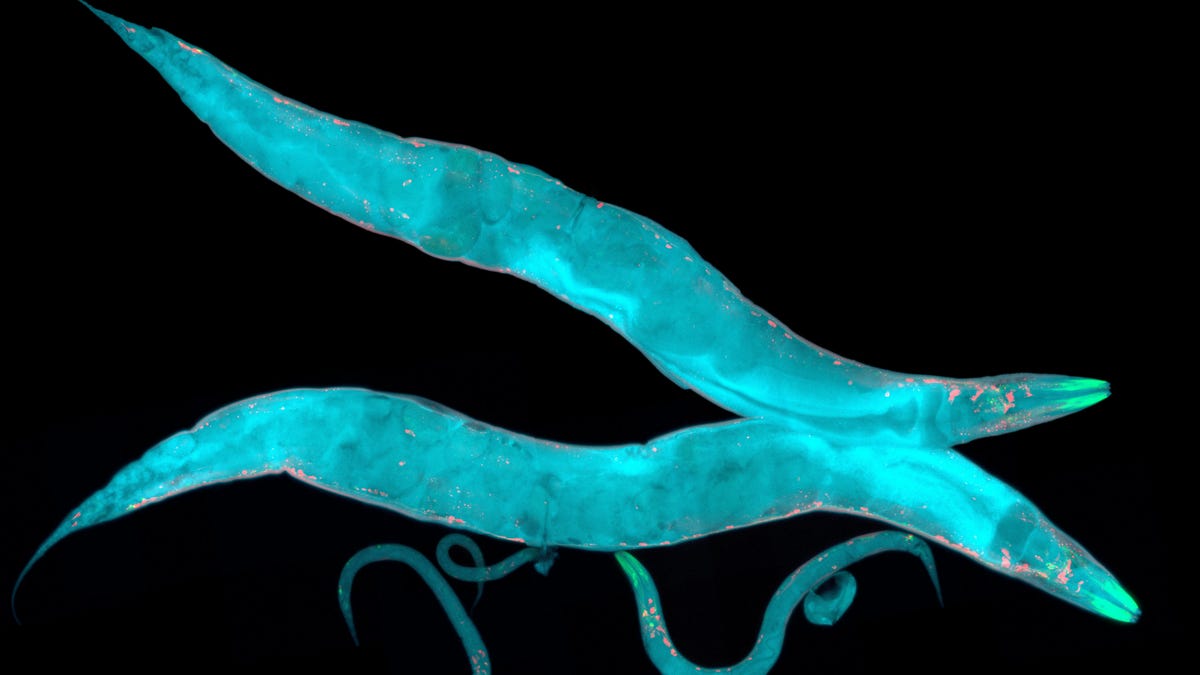

The new study was conducted by scientists at the University of Oregon, led by biologist Shawn Lockery. Lockery and his team had been studying Caenorhabditis elegans, a tiny free-living roundworm, or nematode, for a long time. But like so many stories involving cannabinoids, this research only happened on a whim.

“In 2015, cannabis was legalized in Oregon. At the time, our laboratory at the University of Oregon was deeply involved in assessing nematode food preferences as part of our research on the neuronal basis of economic decision making,” Lockery told Gizmodo in an email. “In almost literally a ‘Friday afternoon experiment’—read: ‘let’s dump this stuff on to see what happens’—we decided to see if soaking worms in cannabinoids alters existing food preferences. It does, and the paper is the result of many years of follow-up research.”

Advertisement

The team’s findings were published on 4/20, of course, in the journal Current Biology. They appear to show that C. elegans worms will eat more than usual when exposed to the endocannabinoid anandamide, and that they’ll gravitate toward the foods they have a preference for. Other experiments showed that this behavioral change was directly tied to the presence of the worms’ cannabinoid receptors and that the cannabinoid primarily affects their olfactory neurons. They also bred worms that had their cannabinoid receptors replaced with those found in humans, and they still responded like before.

C. elegans is a popular lab test subject. Past research had already found that the worms produce their own endocannabinoids (seven in total) and that these endocannabinoids play many roles, including controlling the regrowth of neurons after injury. But this seems to be a novel discovery.

Advertisement

“This is the first time hedonic feeding (the munchies) resulting from cannabinoid exposure has been demonstrated in a non-mammalian organism. Moreover, we have demonstrated this effect in a tiny worm with a nervous system of only 302 neurons. For comparison, the human nervous system has 86 billion neurons,” Lockery said.

The findings have some implications for understanding evolution. They suggest that the neurological wiring underlying this hunger effect arose long before humans or C. elegans were around. Many researchers believe that the endocannabinoid system evolved in part to help animals survive extreme conditions, Lockery notes. One possible explanation for why the munchies happen when animals are exposed to cannabinoids is that it drives them to seek the most energy-dense foods—exactly the sort of snack needed in an emergency situation like pending starvation. And since worms made to have human cannabinoid receptors still felt hungrier, that also suggests this process hasn’t really changed much over time.

Advertisement

“The fact that we share this response with nematodes is significant because the evolutionary lines leading to modern nematodes and humans diverged some 500 million years ago. That means we share a common ancestor who got the munchies when starved. This realization helps us better understand our place in the universe of animals,” Lockery said.

This kind of research could also pay off medically down the line. C. elegans are widely studied as a model for many human diseases. But if these worms get the munchies like us, that could open up more basic research into drugs that can potentially treat metabolic disorders by interacting with the endocannabinoid system.

Advertisement

Lockery and his team plan to continue studying the inner workings of worm munchies. But they’re also fully aware that people will be tickled by their findings, and that’s a worthy goal itself, they feel.

“In addition to indulging our scientific curiosity, we felt that a positive result would be both amusing and thought provoking for the general public. Science that first makes you laugh, then makes you think,” he said.

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews