Everyone likes to hear music their own way, whether it’s soaked in bass, has a little extra treble for definition, or highlights some punchy mids to make guitars growl a little more. Mastering the equalizer of your headphones, stereo receiver, or streaming service’s built-in EQ is an art form in and of itself, whether you’re a producer, engineer, DJ, or just a music lover with an iPhone and a Spotify account.

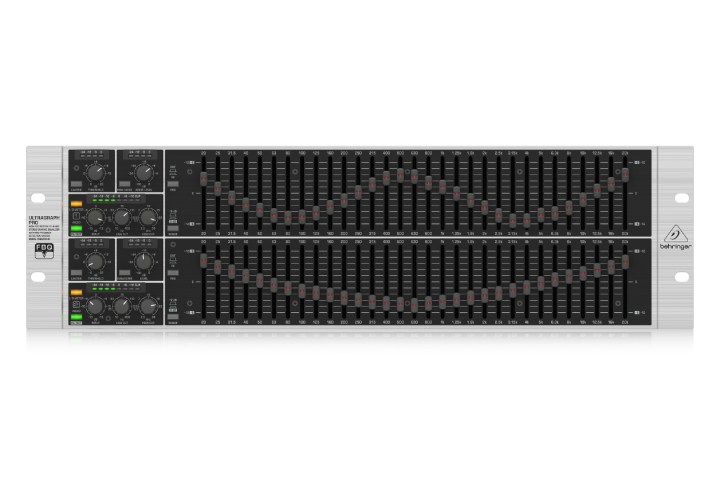

The equalizer, or EQ, has come a long way since your dad’s graphic EQ with the tiny little sliders that he never quite understood — although messing with them somehow made his Zeppelin records sound “rad.” But for most devices you’ll encounter these days, it’s all done digitally.

Understanding how exactly an EQ works and using it properly will put the power of sound sculpting at your fingertips and can get you closer to the sound you want from your gear. But it can be intimidating, so we’re here to help with our top-to-bottom guide to mastering your equalizer for the perfect sound.

Why do I want to use an EQ?

There are several reasons why you might want to use some EQ on your music, and they range from simple personal preference to more complex reasons such as format quality/characteristics and, perhaps most importantly, the effects that the devices and playback systems we use have on the music we listening to.

Let’s start with the most important: preference. Music is a personal endeavor and everyone likes what they like. But more specifically, because of the unique shapes of our ears, and even the hearing issues we may develop as we age, everyone hears music differently. Maybe you like a little extra treble (or have a harder time hearing it) or you prefer a heavier thump in the low-end — EQ gives you the freedom to tailor the sound to the way you like it.

Then there are the headphones, speakers, and other devices we use to listen to music. Electronics manufacturers have their own ideas about what a piece of gear should sound like, but EQ lets you have your say. Maybe you have a bass-heavy pair of headphones that you need to tone down a bit. Or maybe those vintage speakers you found sound a little muddy in the mid and high frequencies — EQ can clean some of that up and help them sing.

Also, we don’t always get to listen to music in ideal environments. The shape of the room or ambient noise can each have a nasty effect on how our music sounds. An EQ can help.

The music you’re listening to also plays a factor. Not only do the natural sounds of the track respond uniquely to different EQ levels, but in the case of digital music, you may also need to cover imperfections introduced by certain file compression formats that can affect the overall audio quality. With these variables in play, an EQ serves an invaluable role for anyone serious about their jams. With it, you can pull out the distinctive shimmer of hi-hat cymbals otherwise drowned out by a dominant vocal track, or even help mellow out the narrator’s voice in an audiobook.

What does an equalizer do?

At its most basic definition, an equalizer manipulates frequencies. The technology first took off as a piece of analog electronics that was initially used in recording studios before making its way into the home. Whether analog or digital, an EQ is used to adjust different elements of sound to achieve an end result that appeals to the listener.

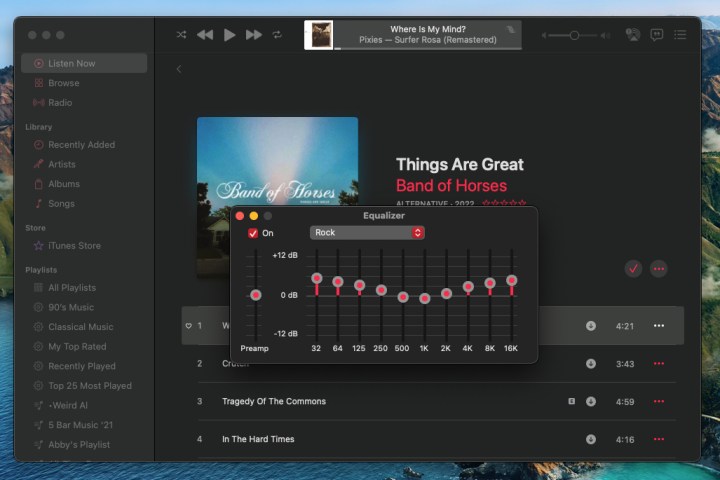

Most people are aware of the basic three levels of equalization — bass, mid, and treble — that you have likely seen on your parents’ home stereo receiver. They’re simple: if you wanted more low end, you goosed the bass; if you like to hear the cymbals and wanted to add some shimmer to the sound, you’d likely add some treble. Speaking more digitally, you may also associate EQ with effects like reverb or echo, or popular EQ presets like “Rock,” “Jazz,” or “Concert,” among others built into popular devices and headphones. But the kind of EQ we’re talking about here offers control over the different sound registers to achieve a refined result. If used properly, EQ can smooth out audio for just the right touch.

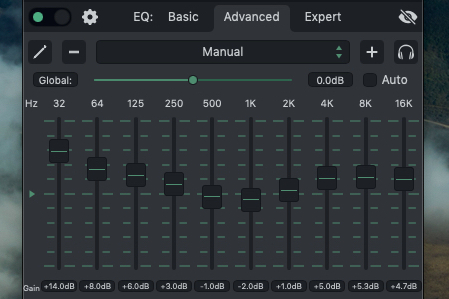

The graphical EQ — which is what we’re going to focus on for most of our walkthrough — looks like a graph (no kidding!) with frequencies on one axis and decibels (dB) on the other. From left to right, you’ll find “sliders” that allow you to adjust certain frequency bands up or down along the dB scale. Bass frequencies start on the left, with midrange frequencies in the middle, and treble on the far right (like a piano).

If you’ve already got a firm grasp of what frequencies and decibels are, feel free to skip ahead to the “Playing with your EQ” section, or even our “Parametric EQ” examination (if you’re a heavy hitter). If not, the following little snippet of Acoustics 101 will probably come in handy.

Frequencies

All sounds — everything you hear — are essentially vibrations that we can visualize as waves moving up and down at different speeds, or frequencies. The faster the wave moves, the higher the pitch. For example, bass frequencies — such as those you hear in a hip-hop groove — move very slowly, while higher pitches (treble) like the chime of a triangle move very quickly.

Every pitch a musical instrument plays has a core frequency measured in hertz (Hz), which can be likened to a speedometer reading for the waveform. Hertz measures how many times (i.e., the frequency) a wave completes an up-and-down cycle in one second. If the wave moves up and down 50 times in a second, that’s expressed as 50Hz. At the theoretical limit, a human can hear from 20Hz to 20kHz (20,000 cycles). In reality, though, most human hearing tops out around 15kHz or 16kHz — the older you are, the less treble you can hear.

All of the sounds you’ll ever hear lives in this 20Hz to 20kHz zone, and thus those are the numbers that will border your typical EQ. Most of the pitches your ears really focus on fall between 60Hz and 4kHz — that’s the meat of the sound. A piano’s highest note, for instance, lives at 4,186 Hz (around 4.2kHz). There are also sounds called overtones, and an EQ will affect them, too. These sounds — which primarily reside in the 10kHz to 14kHz range — aren’t something that your ears naturally hear, but they have an effect on the sound as a whole, so it’s important to keep this in mind when messing around with that section of the treble band.

Decibels (dB)

The decibel (dB) is the unit of measurement used to express volume level or loudness. When you move a slider up or down on an EQ, you are increasing or decreasing the loudness of that particular frequency. It’s important to know that small dB adjustments can have a significant effect on the sound, so tread lightly. It’s wise to start with a 1 dB to 2 dB change and move up or down from there. Since decibels use a logarithmic scale, a 5 or 10 dB change represents a dramatic increase or decrease to a particular frequency band.

Playing with your EQ

Finally, the fun part! Now that you’ve got a grip on what your EQ does, it’s time to start playing around with making adjustments. Go ahead and start playing some music that you are familiar with, pull up your EQ, and move some sliders up or down to hear in action what you’ve been reading about. You’ll soon find out that small adjustments can have a pretty wild effect on how things sound. Below, we’ll give some direction on how to approach things.

Almost any pro sound engineer will tell you the first thing you want to try with EQ is to decrease the level of a frequency, rather than increase others around it. Expanding too many frequencies can make the music sound muddled, and with a little shift here and there, you can subtract a bit of the irksome sound and get closer to what you’re looking for. That’s not to say an increase in a frequency range isn’t necessary at times, but you should always start with subtraction. Remember, too, that any change in EQ will not only affect the frequency range you’ve chosen but also how the rest of the frequencies interact with each other.

It’s normal that you may have to boost the overall volume after reducing any frequencies. For instance, if you want more bass and treble in general, you can pull down some of the midrange sliders, then boost the volume a bit and see what you think of the result. Not exactly right? Then it’s time to get more targeted with your adjustments, and for that, you’ll need to know what each frequency sounds like. We’ve got a guide for you at the end of this article that spells things out pretty nicely.

What about EQ presets?

EQ presets such as “Rock” and “Jazz” are a quick-and-dirty way to get to a different kind of sound without a ton of effort. While these probably won’t give you the exact sound you’re looking for, they can be handy for getting you started. You might want to start with “Flat” or with a preset, then customize it until it is just right.

Some streaming services have EQ slider adjustment options baked into their apps, such as the ones in the desktop versions of Apple Music (the iOS version only has presets) and Spotify (has it on the desktop and mobile apps). These will actually show you what the frequency curve looks like when you select a preset. This can help you understand what different EQ settings can do for you. Other services, such as Tidal, Amazon Music Unlimited, YouTube Music, and Qobuz, do not offer native EQing options.

A couple of notes here, though. While the EQ that is built-in to music service apps is OK when you have no other method of equalization (perhaps your powered speakers are a little lacking in low-end and you want to give them some oomph), we recommend doing your EQ tweaking as close to the listening device as possible. For speakers, do it with the receiver or amplifier; in your car, use its system EQ; and with headphones, use the DAC (digital-to-audio converter) or headphone amp’s EQ (even the app that comes with your headphones is preferable). If your music service doesn’t have any EQ, you’re fine. For Spotify and Apple Music, just turn them off as you don’t want to double up on EQ.

Parametric EQ

Parametric EQs can be tricky, involved, and not for the faint of heart or inexperienced user. They’re generally reserved for recording and mixing, but they do show up in apps for speakers or headphones from time to time. Using a parametric EQ involves targeting frequencies with a band of around five to seven movable control points set along the happy 20Hz to 20kHz frequency spectrum mentioned above. Each of the points is visualized along the X/Y axis; the vertical plane represents loudness (in decibels), the horizontal is for frequency. In the digital realm, a parametric EQ looks a bit like the old arcade game Galaga, with the moveable EQ points acting like your cannon. (Luckily, there are no descending aliens.) With us so far?

Targeting your efforts

As promised, we’ve provided a breakdown of the frequency spectrum to help you get your head around which sounds live where. If you’re ever stumped, this guide can help you drill down to the offending (or lean) frequency to help you make a more effective adjustment. Below are guidelines, not steadfast rules, and your own auditory input is what makes this process all the more personal and enjoyable. And that’s the point: Have fun!

Sub-bass: 20Hz to 50Hz

While humans can technically hear down to the depths of this register, most of these frequencies are less cerebral and more gut. Somewhere in the middle of this register is where your subwoofer will make that eerie sound of deep space in sci-fi movies, and these frequencies can add some serious, unearthly power. However, you would very rarely want to add more of this sound, and taking away from here can help give the music more overall clarity.

Bass: 50Hz to 200Hz

The majority of the time, a stalwart hip-hop groove will start at or around 60Hz. The foundational, big-hitting lower register that spouts forth from your subwoofer rests in this domain, including the heavy punch of the kick drum, and even lower tom drums and bass guitar. Moving up toward the 200Hz line begins to affect the very lowest boom of acoustic guitars, piano, vocals, lower brass, and strings. If the music is too darn heavy, or not heavy enough down low, a bit of an adjustment here will help.

Upper bass to lower midrange: 200Hz to 800Hz

Rising above 200Hz starts to deal with the lighter side of the low end. This region is where the meatier body of an instrument hangs out. Adding EQ volume around the middle of this spectrum can add a bit of oomph to richer tones, including the lower end of vocals, deeper notes from synthesizers, low brass and piano, and some of the golden tones from the bottom of an acoustic guitar. Lowering the level a bit here can clear up some space, and open up the sound. Moving to the 800Hz region, you’ll start to affect the body of instruments, lending more weight with addition, or lightening the load with subtraction.

Midrange: 800Hz to 2kHz

This area is a touchy one that can change the sound quickly. Putting on the brakes in this region can take away the brittle sound of instruments. Adding some juice, especially toward the top end, can give things a metallic touch, and can wear down your ears quickly if pushed.

Upper mids: 2kHz to 4kHz

As mentioned above, this register is where your ears aim a lot of their focus. Adding or subtracting here can raise or lower the snap of higher instrumentation quickly. Sounds like the pop of snare, and the brash blare of a trumpet can all be affected here. Adding a little push here can give more clarity to vocal consonances, as well as acoustic and electric guitar and piano.

Presence/sibilance register: 4kHz to 7kHz

This is commonly referred to as the presence zone and includes the highest range of pitches produced by most natural instruments. Boosting the lower end of this scale can make the music sound more forward, as if pushed a little closer to your ears. Backing it off can open the sound and push instruments away for more depth. The upper end of this region is also responsible for the sharp hissing “s” of vocals, known as sibilance. If sharp consonants are popping out at you like the bite of a snake, cutting a few dB from around 5kHz to 7kHz can solve the issue, and save you some pain and suffering.

Brilliance/sparkle register: 7kHz to 12kHz

Raising or decreasing the level at the lower end of this register can help bring some vibrancy and clarity, adding a tighter attack and a more pure sound. If things are a little too sharp or causing some pain after listening for too long, lowering the bottom end of this register can help out quite a bit. Toward the top is where things start to space out into less tangible definition, moving away from what you can hear and more toward what you can feel. That shimmering resonance at the tip of a cymbal crash floats around in the regions of this space.

Open air: 12kHz to 16kHz

Once you get up here, things become more subjective. The bottom registers continue to affect the higher overtones of instrumentation, and synth effects from electronic music can pop around in that region as well. Moving further up, it becomes more about creating a spacier, more open sound. There are very few points in which you’d want to affect the sound much around 14kHz or above — many older listeners won’t be able to even hear these sounds. If you want to boost a bit of space in the belfries of the music, you can add some level here. Too much, however, will make things start to sound synthetic.

Editors’ Recommendations

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews