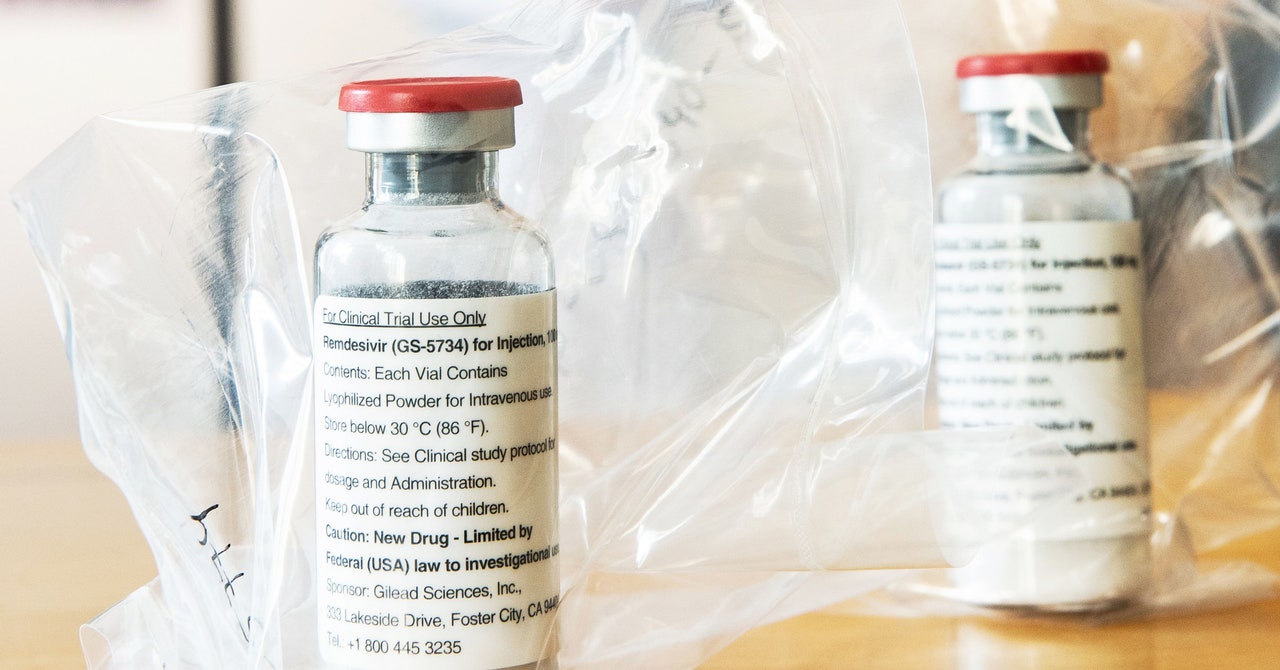

Two weeks ago, news came out that the United States has secured the entire current global supply of remdesivir, one of the two drugs shown so far to be effective at treating Covid-19. Even for the richest nation in the world, this will be a massive expenditure: more than half a million treatment courses priced at $3,120 each for most hospitals, without any government attempt to negotiate a better price. In other words, the US healthcare system is poised to spend on the order of $1.5 billion for this medication. What justifies such a high price, especially given remdesivir’s cost of production is roughly ten dollars per course?

Scholars and pharmaceutical executives defending remdesivir’s price primarily anchor their arguments on three key points: (1) the drug provides substantial value, and thus is worth the price; (2) companies need to recoup the cost of research and development investment in the drug; and (3) high prices for remdesivir today incentivize future development of Covid-19 treatments. None of these arguments holds up.

WIRED OPINION

ABOUT

Rohan Chalasani (@rohanchalasani) is a medical student at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Walid Gellad (@walidgellad) is a physician and policy researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, where he directs the Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing.

Remdesivir certainly has value, but the data right now supports a price lower than what its maker, Gilead Sciences, Inc., is charging. A clinical trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health found that the drug shortens recovery times for many Covid-19 patients. However, remdesivir has not yet been proven to reduce mortality—to save lives. While the NIH trial found a numerical improvement in survival, the difference did not reach conventional thresholds of statistical significance or certainty; and a smaller study published in the Lancet also did not find an improvement in mortality. If remdesivir does not offer a mortality benefit, then the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review—an independent drug-pricing watchdog—puts the “value-based price benchmark” for the drug at $310 per treatment course. That’s about one-tenth its current price. Even if a mortality benefit from remdesivir were eventually confirmed, ICER pegs its value-based price at $2,500 to $2,800 per course, still 10 to 20 percent lower than what we pay right now.

But, to step back, why should we even try to price drugs based on notions of value in the first place? We don’t price any other life-saving healthcare service in that way. Heart transplants, trauma surgeries, emergency appendectomies and c-sections—none of these life-saving interventions are priced based on their ‘value.’ If they were, their prices would range anywhere from $50,000 to $150,000 per additional quality-adjusted life year they provided; and a life-saving surgery for an infant could carry a price tag in the hundreds of millions. Moreover, if remdesivir should be priced based on its value, then what about dexamethasone, a decades-old generic steroid, that was just found to reduce mortality in Covid-19 patients? That drug, often used to treat inflammation, costs less than $1.50 per 6-mg tablet today. Would it be okay if a generic drug company massively inflated the price overnight to align with its new value?

What about the cost of investment—does Gilead need to charge $3,120 for remdesivir to make up for all the time and money that the firm put into it? Even if it were appropriate to set a price based on a sunk cost—and most economists would argue that it’s not—remdesivir’s development has been buoyed by incredible amounts of government investment. The 2015 paper detailing the discovery of remdesivir was the product of a public-private partnership between scientists from Gilead, the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, and the US Centers of Disease Control and Prevention; yet government employees were excluded from the molecule’s patent. Financially, remdesivir’s development has been directly supported by at least $70 million of taxpayer money—including funding for its initial discovery, studies of its effects on coronaviruses, and its Covid-19 clinical trials. Investment in remdesivir hasn’t been Gilead’s alone, and the drug’s price should accordingly reflect the contributions of taxpayer funds that offset the costs of its development and commercialization.

Finally, we arrive at remdesivir’s price as an incentive for future drug development. This point of view was recently explained in a Washington Post op-ed from Northwestern University economist Craig Garthwaite, who argued that since remdesivir is not the last treatment for Covid-19 that we’ll need, its price is a crucial signal to potential market participants. If remdesivir were too cheap, other companies might be disincentivized from pursuing the cures and vaccines we need.