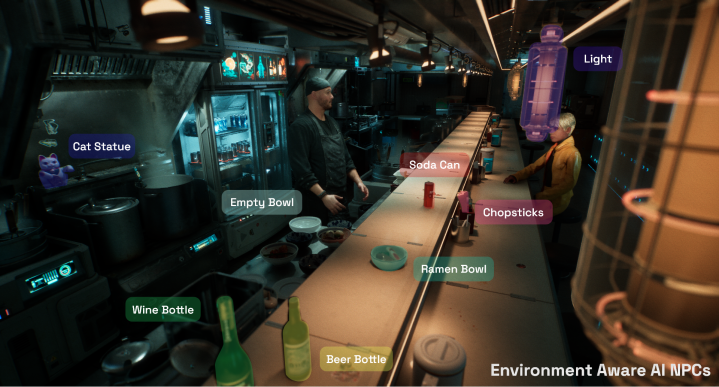

Earlier this month, I witnessed a digital miracle. In a press briefing ahead of CES, Nvidia showed off a demo for its Ace microservice, an AI suite capable of generating fully voiced AI characters. I watched in awe as a demoist spoke to an in-game NPC through a microphone, only to have the digital character respond in real time. It was a true sci-fi feat, but there was one question: How did it learn to do that?

Nvidia gave an ambiguous response, claiming there was “no simple answer.” The statement set off a firestorm, as users on social media assumed the worst. Speculation arose that Ace was trained on content Nvidia didn’t have the rights to. Nvidia later claimed it’s only using data it’s cleared to use, but tensions were still high. A mountain of ethical and artistic concerns left gamers skeptical.

Among the spectators watching it all unfold from the sidelines was Purnendu Mukherjee. The software engineer wasn’t another face in the crowd; he created the AI tech at the center of a debate he didn’t start. Mukherjee is the founder of Convai, the generative AI company powering Nvidia Ace. Rather than sitting back and watching someone else try to explain his tool, he was eager to set the record straight.

Speaking to Digital Trends, Mukherjee sat down to answer some ethical concerns in a wide-ranging interview about AI tools like his. He offered his thoughts on everything from unemployment fears to worries that AI would sap humanity out of art. For Mukherjee, that’s far from the truth. The Convai founder sees an optimistic future where artists work hand-in-hand with AI to realize their creative visions fully. But when it comes to the hot topic of data usage, his explanation could raise more questions than answers.

Can AI and artists coexist?

As a kid, Mukherjee was always curious about the human mind and how it worked. He started learning about AI in high school but was turned off by the more rigid rule-based systems of the time. His interest was piqued much later in 2015 when he studied deep learning in a lab in India. After moving to the U.S., going to grad school, and working at Nvidia for a spell, Mukherjee eventually split off on his own to found Convai in April 2022. He bootstraped the company for 10 months out of pocket.

Mukherjee is a gamer at heart. He grew up playing competitive titles like Counter-Strike at a local internet cafe. It’s there that he start to imagine how AI could improve games, joking about the shooter’s braindead bots. That thought has now blossomed into a successful tech innovation that uses several AI processes to generate fully-voiced NPCs that can respond to real-time prompts from players. His goal? To make games more engaging.

“Take Baldur’s Gate 3 or The Witcher,” Mukherjee tells Digital Trends. “They have such incredible stories. Such lovingly, passionately written stories. But you, as a player, can’t get to the depths of it because there are just a few narrative lines you can explore from the NPCs. Given the tech that’s available today, those NPCs could have a life of their own and interact with you while staying in character and give you more information if you want to go deeper into the narrative designer’s mind.”

That statement kicks off a long interview where Mukherjee rebuts a string of interconnected concerns about AI. When I asked if Baldur’s Gate 3 would be the beloved game it is without its intentional writing, we went down a rabbit hole unpacking the relationship between machines and artists. He’s clearly come to the conversation prepared as if he’d spent a week studying skeptical social media posts. He quickly emphasizes that AI isn’t a replacement for artists; it needs them.

“I only see narrative designers in more demands, not less,” he explains as he outlines how AI could create more jobs for artists. “The writers aren’t just writing to create backstory and narrative. They are also writing for test purposes. The way you feel confident to ship a generative AI-based NPC in your multi-million dollar game is that you need a robust test set. You need hundreds, if not thousands, of back-and-forth interactions, ideally coming from that same narrative writer … If you try our platform, it requires you to write a backstory and upload a bunch of written documents from the writer themself, who is writing the mind of the character. It effectively requires ten times more writing than what is done today.”

This line of thinking becomes a common thread in our conversation. Mukherjee often emphasizes that he believes generative AI tools will require just as many, if not more, artists to train the tech properly. At one point, he posits that great AI will make games better, which will, in turn, lead to more sales, convincing studios to pay voice actors more since their work training these tools is so critical to creating high-quality games with next-level engagement. It’s an optimistic vision considering that the video game industry is currently in the middle of a mass layoff wave that has left thousands out of work.

Mukherjee isn’t blind to that reality, nor does he deny that a rise in generative AI could have an impact on jobs. He describes that as more of a natural shift that isn’t so different from anything we’ve seen in previous tech advancements like this. People will have to adapt and learn to work with AI to create their work.

You still are the creator, master, and controller of it.

I dig in further. He’s discussing AI’s impact in terms of how it will impact jobs, but what about artists who make games because they want to make intentional, hand-crafted content? Surely, it’s not so simple as telling artists to become AI engineers. Mukherjee doesn’t believe that’s the solution; rather, he feels it’s more a matter of understanding where art and tech intersect.

“AI is the same thing as Adobe Photoshop or Unreal Engine,” Mukherjee says. “Yeah, games were made before Unreal Engine was a thing. People still hand-crafted it. But can you not express yourself with the best art in Unreal Engine? You can. Take any 3D video editing software. You still have that art because you still have to do the same painstaking level of small detail. With AI-generated stuff, all of that is true. The aspect of hand-crafting is still there. You just have a tool that has more expressive power, but you still are the creator, master, and controller of it.”

The data ladder

It’s clear that Mukherjee sees AI as a helpful tool that can support artists rather than replace them. During our conversation, he circles back to a few key points about how AI needs humans, thoroughly addressing common concerns. Where things start to get tricky, however, is when the one word AI companies seem to dread gets brought up: data. While creators contend that AI models trained on their creations are stealing, some key AI developers claim they cannot train models without massive data input, including copyrighted works. Mukherjee floats the idea that people should be paid when their data is used to train AI models.

“I think there needs to be a way where people who have significant contributions to the data sets are compensated well,” he says. “Whether that’s the New York Times or Reddit, the source needs to be licensed. It’s not a simple way, but that’s what it’ll get to in my opinion. And whatever is the most correctly done, especially when we’re using it at a commercial level, of course, we’ll choose that one.”

When pressed on Convai’s own data set, Mukherjee maintains that the company only uses data it has the rights to. He notes that it’s not even possible to randomly scrape the kind of data the tool needs, considering that it’s charting new territory. It’s a logical explanation, though one that he quickly debunks himself.

“We do use base models, either from OpenAI or licensed open source models,” he says. “They have to be commercially licensed and ethically sourced. We’re very careful about those things. And when it comes to text-to-speech, we’re extremely close to ensuring that we work very closely with voice actors. In our case, it requires more voice actors, not less!”

The name OpenAI raises an eyebrow. The company is currently in legal trouble, as The New York Times has sued it over its “unlawful use” of its writing to train bots like ChatGPT. OpenAI doesn’t dispute the charge. In response to the U.K.’s House of Lords Communications and Digital Select Committee, the company writes, “It would be impossible to train today’s leading AI models without using copyrighted materials.”Considering that Convai’s model is built on OpenAI’s work, I prod Mukherjee: How can he ensure that no copyright materials were used?

We don’t know which model is using which data set completely.

Mukherjee draws a subtle distinction: Convai isn’t using OpenAI’s data, just the models trained on it. It’s a bit of a linguistic loophole. Mukherjee seems to believe that since Convai isn’t using the data directly, the company is still above the board when it comes to copyright disputes. When pressed for clarity on how using the models differs from using the data it may not have the rights to within it, the situation gets hazier.

“It’s not clear which model has which data,” he clarifies. “We don’t know because that’s not clear for us. Let’s say OpenAI is giving five models, Nvidia is giving four models, Meta is giving three models. We’re using whichever works best for our use case. We don’t know which model is using which data set completely.”

Mukherjee’s argument seems to be that Convai isn’t responsible for how other models handle data. He has no control over that. All he can do is make sure that its own data use is ethical and hope that the models he’s building on are, too. But his earlier claim that Convai would “of course” build on the most ethical AI model doesn’t really hold up, considering he’s currently using one that’s at the center of a copyright lawsuit. Another line reads differently in that new context: “We’re extremely close to ensuring that we work very closely with voice actors.” Extremely close implies Convai isn’t actually there yet.

Complicated conversations like this may explain why Nvidia declined to answer my question about data usage in the first place. The truth is that all of these tools are built on top of one another. Ace uses Convai, which uses OpenAI. There’s a ladder of data; the further you climb, the harder it is to see who’s at the bottom. Nvidia’s claim that there is “no simple answer” about data usage is right, but there’s a more honest answer: It simply doesn’t know. Nvidia likely won’t have to answer questions in court, but if OpenAI loses its battle, the entire ladder could fall.

A civilization-level change

As we untangled that mess, I brought up the idea of regulation. Should the government step in to set some guardrails on the tech? Mukherjee does think some is needed, though he believes it needs to be done carefully. His worry is that too much regulation could suffocate innovation. And at the end of the day, he truly believes that any risks AI presents don’t invalidate the potential power of the tech.

“What is AI today? AI today is like a car,” he says. “Are cars not dangerous? Of course, they are! You can totally kill a person with a car, but we drive cars all the time. It’s so risky, but it’s net positive overall. I see AI as the same thing. We will need regulations on how you can and cannot drive a car. If you drive them illegally, you will be punished. It’s going to be the same with AI eventually.”

There is going to be change, and change hurts people.

It’s a bit of a grim comparison, but throughout our conversation, Mukherjee has nothing but optimism about AI. He truly believes it will be a net positive for society in the long run, so long as companies remember to keep humanity at their center. He hopes to see a world where tools like Nvidia Ace support artists, not take jobs from them. He doesn’t see a doomsday future ahead of us where everyone loses their jobs to machines, but he does accept that it will force people to adapt.

“There is going to be change, and change hurts people,” Mukherjee says. “It’s the same kind of change whenever a new kind of technological shift happens. That’s a civilization-level change. There’s going to be a bunch of new jobs created and a bunch of older, more traditional jobs that will be of less demand. Let’s say when we moved from horse carts to cars. People who had horse businesses definitely had to find something else … Generative AI is going to create a whole new set of possibilities. It’s going to be significantly net positive for humanity as a whole, but it will require a level of job shift.”

At the end of the interview, Mukherjee thanked me for speaking to him and getting him a chance to set the record straight. He notes that a lot of press that covered the Nvidia Ace announcement didn’t even mention that Convai built the tech under it. He sounds just a touch frustrated that his company isn’t getting the credit it deserves. I point out the irony in that feeling, noting that it’s exactly how artists currently feel watching AI tools scrape their work and spit it back out as their own.

“That’s a great point!” he says with a big laugh and, perhaps, some newfound clarity.

Editors’ Recommendations

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews