Depending on what era of gaming you grew up in, the name Jeff Minter could mean everything or nothing to you.

The visionary developer behind Llamasoft, one of the industry’s most eclectic studios, was practically gaming royalty from the 1980s to the mid-90s. He made a name for himself with titles like Gridrunner and Revenge of the Mutant Camels before creating a true magnum opus in 1994’s Tempest 2000. While he hasn’t stopped making games since then (he even released a new one last week), Minter isn’t exactly a household name outside of game history buffs these days. That’s not because he’s no longer producing great work; it’s the harsh reality of a commercialized industry he’s always revolted against.

Now, Minter is getting his due in Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story, the latest interactive documentary from Digital Eclipse’s Gold Master Series. Like last year’s The Making of Karateka, the unique project preserves Minter’s classic games and contextualizes them with loads of archival material. The result is, unsurprisingly, another must-own package for anyone interested in video game history.

What’s more vital, though, is the eerily relevant story that’s woven between games. The Llamasoft collection spotlights an almost prophetic Minter who accurately predicted the endpoint of the game industry’s quest for commercialization. It’s a sobering snapshot of how we got to where we are today, even if its Atari-washed happy ending obscures the truth a bit.

What a trip!

Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story serves two distinct functions. On its most basic level, it’s a fantastic retro game collection that pulls together 42 Llamasoft games released between 1981 and 1994 (plus Digital Eclipse’s own modern remake of Gridrunner). These aren’t the kinds of games that you can buy in a dozen retro game collections currently floating around digital marketplaces. It’s a thoroughly curated collection of Minter oddities ranging from career-defining hits like Iridis Alpha to his stretch of early 90s shareware releases.

Even if you skip all of the documentary features included here, there’s a lot to glean from simply playing the fantastic suite of titles chronologically. They offer a window into Minter’s psyche, showing his creative evolution in real time. The timeline begins with crude recreations of classics like Centipede (a project Minter made without actually having played the original), but each game slowly takes on a distinct shape as the artist finds his voice. Riffs on established games of the time combine with Minter’s love of Monty Python-inspired absurdity, psychedelic art, and animals with legendary results.

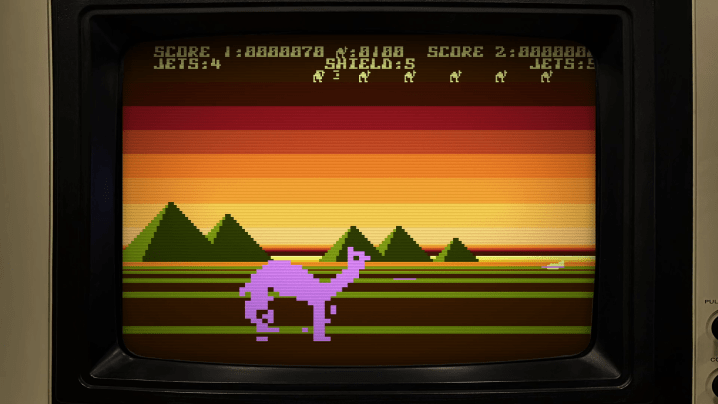

A project inspired by the video game version of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back and its AT-AT fights morphs into a wild arcade game about shooting an enormous camel. That later turns into Revenge of the Mutant Camels, which inverts the Star Wars formula by letting players control the giant beastie instead of attacking it. Each time Minter builds on an idea, it gets wackier, from the bafflingly bizarre Mama Llama to the fantastic Llamatron: 2112. Like The Making of Karateka, Digital Eclipse pulls together a pivotal historical document that emphasizes the importance of innovation and iteration.

That’s best exemplified in the package’s journey to its crown jewel, Tempest 2000. The Atari Jaguar hit still feels fresh by today’s standards, delivering a wholly unique space shooter that experiments with space. You can feel that by playing it, but its impact is stronger when placed in the context of the games that came before it. I began to connect the dots between early Minter works like Gridrunner and Laser Zone, both of which challenged design ideas of the time to reimagine how players move in a game. Through that lens, it’s no surprise when those ideas culminate in a system-defining classic like Tempest 2000. It’s a game design seminar tucked into a retro game collection.

Rise of the megagame

What’s just as valuable is the archival material Digital Eclipse has pulled together for the release. The Llamasoft collection tells Minter’s story through photos, design documents, magazine clippings, newsletters, and more. Those additions give crucial context to each game, explaining exactly how something like Colourspace, Minter’s digital light synthesizer tool for Atari’s 8-bit systems, came to be. The only downside of having so many games is that Digital Eclipse only deep dives into a few key titles, with some of his oddest projects passing by with little extra context.

Also missing here is the extra interaction that made The Making of Karateka feel like such a revelation. That project featured ingenious tools that turned the development process into a hands-on museum exhibit. The Llamasoft package doesn’t include anything like that, instead laying out much of its central documentary in long Minter newsletters. Thankfully, those documents are just as engrossing as the games he wrote about in them.

There’s a running theme that comes up throughout the writing featured in the collection. Minter lays out a grim vision of the 1980s video game industry, one that he feels is slowly careening towards a harmful form of commercialization. His writing at the time explains how gaming’s growing popularity had claimed a victim in specialized tech shops that looked for high-quality games. As the industry grew more profitable, chain stores took over and began pushing whatever was popular. That pushed studios to create more safe crowd-pleasers that would get into stores rather than innovation-focused gambles that small shops would want to sell.

“Too many people are trying to make money out of the industry,” Minter writes in the third issue of his Nature of the Beast newsletter, circa 1984. “Companies talk of ‘megagames’ and advertise products far before they’re ready, and often originality is sacrificed just so that a more ‘marketable’ product can be released … The whole scene has become really heavy and commercial. All those breadheads trying to make a million pounds and never mind the games. It’s disgusting.”

If you read that quote without any context, you might think it was written today. Everything Minter discusses is applicable to the lucrative game industry in 2024; he may as well have been writing about Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League or Skull and Bones. Through his writing, Minter predicts an industry where design innovation is doomed to fall to the side as studios try to recreate tried-and-true successes. That’s not how you get to Tempest 2000.

Atari-washing history

Digital Eclipse follows that thread throughout Minter’s career, slowly painting a picture of a genuine genius who is pushed out of an industry that’s no longer friendly to developers who want to make a game about stealing your neighbor’s lawn mower. Though oddly, Digital Eclipse doesn’t carry that tale to its conclusion. The collection more or less ends by celebrating Tempest 2000’s success, quickly explaining that Llamasoft is still thriving today and leaving players with a trailer for a proper film documentary about Minter’s work. It’s all a bit strange, almost like the studio is too close to its subject to acknowledge his waning star power.

The more likely explanation for the ending might just be business, though. In October 2023, Atari announced that it planned to acquire Digital Eclipse — a sensible move considering that the studio had previously made a critically acclaimed collection for the company’s 50th anniversary. As I scratch my head over the anticlimactic endpoint of the Llamasoft collection, that business deal sticks in my mind.

Rather than building up to Minter’s magnum opus, the final chapter reads more like a celebration of Atari history. The climax is less about Tempest 2000 and more about the Atari Jaguar. A great deal of space goes into an aside about the Konix, a failed British video game system that would pave the way for the Jaguar. There’s only one quick mention that the system was a commercial failure; otherwise, the story would have you thinking that the Jaguar was a massive moment for the industry that gave Minter his career. The package even ends with a pair of archival quotes from the developer circa 1995, where he praises the company for bringing him back to mainstream game creation. That’s the note everything ends on, almost feeling like an ad for another unannounced Atari console reproduction.

Context is everything in Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story, so here’s some to consider: Atari has a vested interest in preserving Minter’s legacy. After all, the company published Llamasoft’s latest releases, both Akka Arrh and its newly released VR version. Though Atari didn’t publish this project, and its $20 million acquisition of Digital Eclipse still appears to be pending, I can’t help but wonder if the finalized deal could create a conflict of interest for the studio’s journalistic efforts down the line. I feel like I’m already seeing a tease of that possibility here in what’s an otherwise vital preservation effort.

Admittedly, all of this is the kind of tin foil hat criticism that Minter himself despises, as evidenced by the well-documented spat with Zzap! magazine over a bad review of Mama Llama included here. Perhaps the simpler answer is that Digital Eclipse has told the exact story it wanted to present here — something that would mirror its subject’s own uncompromising attitude. If that’s the case, I can appreciate Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story as an optimistic portrait of a mad scientist who continues to make his left-field art in defiance of a commercialized machine. Maybe we could all use some hope that the video game industry hasn’t squeezed the life out of itself yet.

Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story is out now on PS4, PS5, Xbox One, Xbox Series X/S, Nintendo Switch, and PC.

Editors’ Recommendations

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews