If you’ve been watching a lot of TV during the coronavirus lockdown, then like me you may have noticed an odd collision of ads.

One minute we’re watching a trailer for the new Penny Dreadful in which 1930s Los Angeles is tearing itself apart. Natalie Dormer, as a shape-shifting demon, delivers a line that reflects our long-held deepest fear about human nature: “all mankind needs to be the monster he truly is… is being told he can.”

But this dark diagnosis is followed by one of those heartstring-tugging pandemic PSAs showing our quiet, peaceful, riot-free neighborhoods. “You’re not alone,” they say. “We’re all in this together.” Indeed we are. Consistent and large majorities of the U.S. supports and understands the life-saving science of social distancing — astroturfed protests notwithstanding. Look for the helpers, as Fred Rogers famously advised, and you’ll find them everywhere.

How do we square these views? If we are monsters hiding under a thin veneer of civilization — or even just self-interested egotists at heart, as economists tend to assume — then why are most of us willing to sacrifice our wellbeing to protect vulnerable people we’ve never met? The most coherent, well-proven answer can be found in Humankind: A Hopeful History, a book by Dutch historian Rutger Bregman garnering global buzz ahead of its June 2 release.

You may remember Bregman from a widely-shared, unaired Fox News interview in which he called Tucker Carlson “a millionaire funded by billionaires.” Or from his viral appearance at Davos where Bregman chided billionaires for not paying their fair share of taxes. He’s also the author of Utopia For Realists, which has become a bible for the Universal Basic Income movement.

“Basically, what you assume of other people is what you get out of them,” Bregman said of Humankind when I interviewed him for our series on UBI. “If you assume other people behave selfishly, that’s how they behave.”

The only scientific proof he’d found of people becoming less generous over time, he said, was a 1990s study of first vs. third-year economics students. Their answers on behavior quizzes became less generous the more they were told that humans are basically selfish.

[embedded content]

In fact, we’re hardwired to help. Bregman’s book summarizes a mountain of new discoveries in a wide range of fields that debunk what we thought we knew about humanity.

For example, instead of of “survival of the fittest,” evolutionary biologists and psychologists now talk about “survival of the friendliest.” Over time, without even trying, we’ve selected for social intelligence in our mates. This is why loneliness can literally make us sick (and hence why our COVID-19 lockdown is even more of a show of love).

This is why we’re the only animal that blushes, a strong social signal of shame — and why politicians who have mastered the art of being shameless can take advantage, time and again, of our essentially trusting nature.

Homo sapiens has undergone the same transitions as we caused in wolves and foxes (and still do, in famous Siberian fox domestication experiments): rounder faces; smaller brains that counterintuitively have more connections, and hence more facility for language; more childlike playfulness. Bregman, with a touch of that playfulness, suggests our species needs a new name: Homo puppy.

So why, so often, do we think otherwise? Why do we keep believing Natalie Dormer’s line about mankind being monsters held in check? Because, for centuries, we’ve been spreading and reinforcing one particular, pernicious untruth.

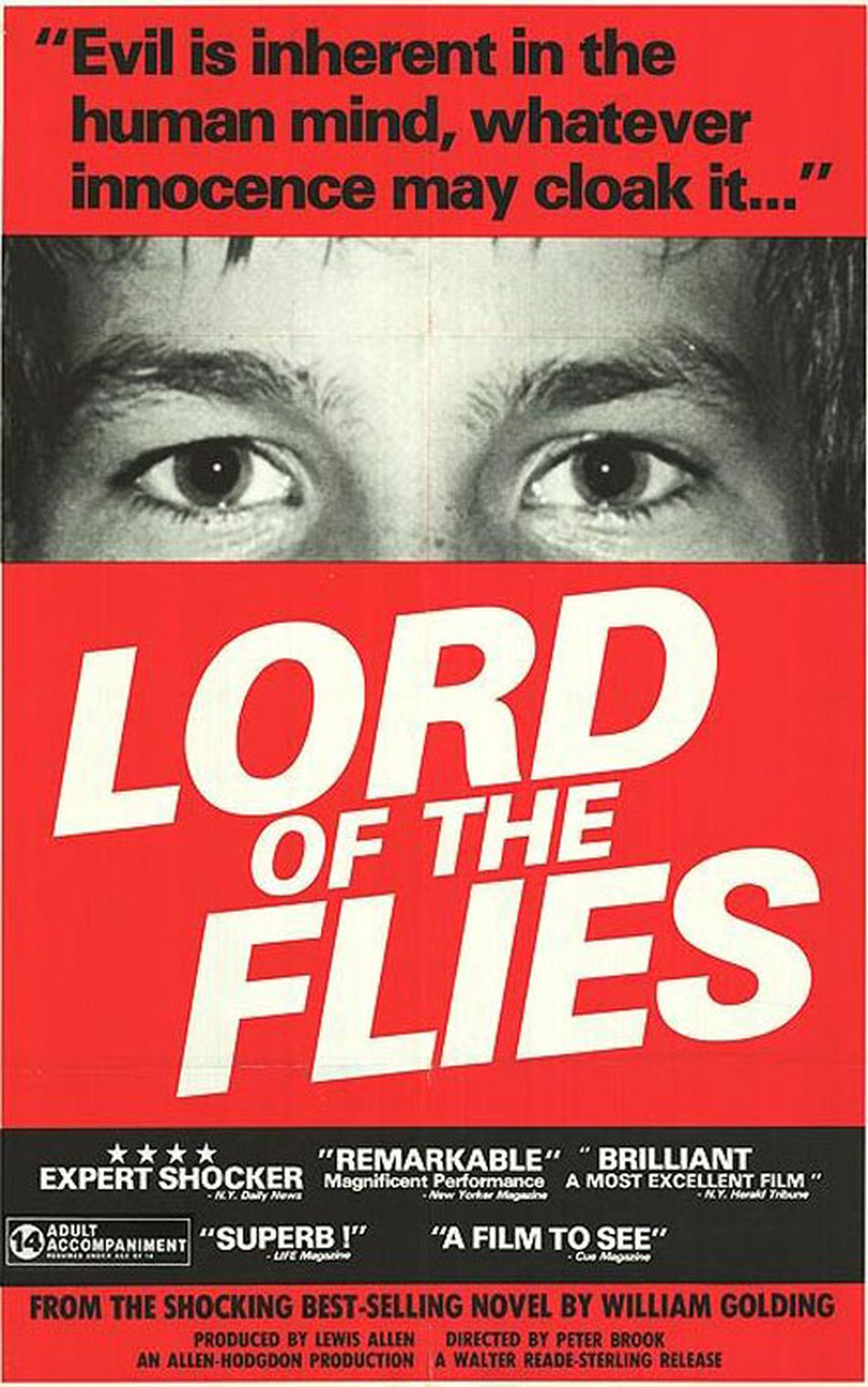

Lord of the Lies

Image: British lion

The best thing about Bregman’s book is that it doesn’t just present you with his optimistic conclusions, fully formed. It takes you on his personal journey, from believing (and teaching) many of society’s shibboleths about inherent evil to systematically tearing each one apart with evidence.

First up: Lord of the Flies, the 1954 novel about a bunch of British schoolkids stuck on a desert island and their descent into bloody anarchy. Like many of us forced to read it at school, Bregman was depressed as hell by what it had to say about human nature. It doesn’t present any scientific evidence, of course, it’s a story, but it feels right. It was filmed twice, and influenced so many other books and films it’s a cliche. Look at a high school today and you think: Yep, these kids are one plane crash away from Lord of the Flies.

But how can we run an experiment to see if kids actually turn into murderous barbarians when left to fend for themselves? Bregman trawled the historical record and found there’s only one test: The little-known tale of a bunch of British teenagers in Tonga in 1965 who stole a boat, tried to make for New Zealand, and wound up castaways on a mostly barren island instead until their rescue 15 months later.

What did these kids do? Stick pig heads on spikes and shout “bollocks to the rules?” No, they sat down together and made rules. After taking days to make fire, they set up a rota system that kept it burning nicely their entire time on the island. They figured out how to collect rainwater and pick berries. If two kids had an argument, they had to walk to opposite sides of the island to cool off. When they came back, doctors declared them in excellent physical and mental shape.

Of course, Lord of the Flies wouldn’t have won the Nobel Prize for literature if it ended that way. Drama often requires exaggerating the darker parts of the human soul. But its author, William Golding, a reclusive alcoholic schoolteacher who beat his own children, actually set out to spread the message that kids are nasty little bastards who need discipline. “I have always understood the Nazis,” Golding said, “because I am of that sort by nature.”

He’s just the first in the book’s parade of villains. Bregman doesn’t draw this connection, but it’s clear that most happen to be privileged white males who figure out how to get famous by fabricating evidence that humans are basically monsters — implying that they alone have the solution.

The prison you make

A still from “The Stanford Prison Experiment” (2015)

Image: Steve Dietls / Coup D’Etat / Sandbar / Abandon / Ifc / Kobal / Shutterstock

Golding wasn’t alone. The same year he published Lord of the Flies, U.S. psychologist Muzafer Sherif conducted something called the Robbers Cave Experiment. He took two teams of well-behaved boys, stuck them in the Oklahoma wilderness, and watched as they turned into knife-wielding warmongers.

Except, as we discovered when the archives were finally opened in 2017, Sherif manipulated the whole thing — dissuading friendships to “create a sense of frustration,” trashing the boys’ stuff and blaming the other side, almost coming to blows when a research assistant tried to stop him. The whole thing was halted when the kids discovered his notes on them, revealing it was an experiment. (Or, as we’d call it today, a reality show.)

Equally unethical was Philip Zimbardo, the psychologist behind the infamous 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment. When a group of students were divided into “guards” and “prisoners,” for a week, the resulting brutality from the guards on their classmates shocked the world. Surely, people reasoned, here was proof of inherent human savagery.

Again, it wasn’t until the 2010s that Zimbardo’s deceit was discovered: He had handpicked the guards, coached them, and suggested their most sadistic methods. One “prisoner” who was taken out of the experiment after having what was widely reported as a breakdown later revealed he was playacting — because he was bored, wanted to study, and Zimbardo wouldn’t let him have his textbooks.

By the time we knew all this, the damage had been done. Zimbardo, who should have resigned from academia, became president of the American Psychological Association. He also helped provide the foundation for the “broken windows theory” via a dubious experiment in which he smashed his own car’s window. That led to a wave of brutal policing across the U.S. in the 1990s, when cops went crazy writing up anyone they could find for minor infractions — mostly minorities, as it turned out — in the belief it drove down crime. A belief that later research confirmed was mistaken.

Thanks to several other flawed studies like Zimbardo’s, U.S. prison reform efforts in the 1970s also ground to a halt. Instead of rehabilitating prisoners, we made their guards and their environments meaner. Bregman contrasts this with Norway, where even in maximum security prisons, guards and prisoners mingle at social events, and prisoners are given meaningful work and dignified rooms. It sounds crazy, it shouldn’t work, and yet only 20 percent of prisoners in Norway are back inside two years after being released. In the U.S., it’s 60 percent.

The evidence is so incontrovertible that even officials from deeply Republican North Dakota decided to modify their prison system after a trip to Norway in 2015. “I’m not a liberal, I’m just practical,” said the director of the North Dakota Department of Corrections, Leann Bertsch. She’d broken down in tears during the trip, her entire world view in tatters. “How did we think it was OK to put human beings in these settings?”

Stop the stories

That’s an excellent question. And the answer isn’t as easy to frame as the tribal conflict between so-called bleeding heart liberals and tough-on-crime conservatives. Bregman points the finger at a lot of causes. In part, it’s both sides’ belief in the “tragedy of the commons,” another psychological concept of selfishness that — you guessed it — isn’t borne out by the actual research. (Its creator was, once again, a racist white male in the 1960s.)

Historically, Bregman says, it’s a hangover from when we switched from being hunter-gatherers to farmers, when authoritarians got people to work the fields by drilling their inherent worthlessness into them. (“No pain, no grain,” Bregman says.) It’s also the legacy of a dispute between 17th century philosophers (Thomas Hobbes said mankind’s life was naturally “nasty, brutish and short” and therefore needed a strong government; his pro-primitive nemesis Jean-Jacques Rousseau couldn’t have disagreed more).

In part, we’ve messed up our studies of ancient primitive cultures, mistakenly believing them to be more violent than they were. For example, everything you learned about the downfall of Easter Island’s civilization may be wrong. There may have been no war between its inhabitants, as Jared Diamond claimed in his bestseller Collapse. A couple of 2016 studies showed, firstly, that only two out of 469 skulls found on the island showed any signs of trauma. Secondly, their stone tools were deliberately blunted, not weapons as Diamond claimed. The rumors of an internal war turns out to be based on a single story told to a visiting researcher in 1914.

This, ultimately, is the problem: We keep taking the wrong stories too seriously, whether they’re Lord of the Flies or Penny Dreadful. And that’s why the pandemic is such a powerful moment, because it’s one of the best chances we’ve ever seen to change the narrative.

“Disasters bring out the best in us,” Bregman writes. “It’s like they flip a collective reset switch and we revert to our better selves.”