“You’re seriously asking for my view on The English Patient?!” the late author David Foster Wallace squirms, midway through a lengthy 1997 PBS interview with Charlie Rose.

The host had been grilling Wallace, ostensibly invited on to discuss his own literary and journalistic output, on range of topics: tennis, teaching, why women don’t like Westerns, depression, and, yes, Anthony Minghella’s Academy Award-winning epic war drama, which had by the time the interview aired already become a Seinfeld punch line.

Watching the interview, it’s clear Wallace, who died by suicide in 2008, bristles at being pressed to purvey rank punditry on the popular culture at large like some kind of dancing monkey. But the exercise revealed how Rose, and large swaths of American intellectual culture circa the late-1990s, thought of Wallace. He was an all-purpose Big Brain who could alight on anything, from politics, to avant-garde authors, to the ethics of shellfish eating, to warmed-over Oscar bait. It is a consummate performance of erudition, shot through with prickly self-consciousness— arguably as impressive, and influential, as Wallace’s whole literary output.

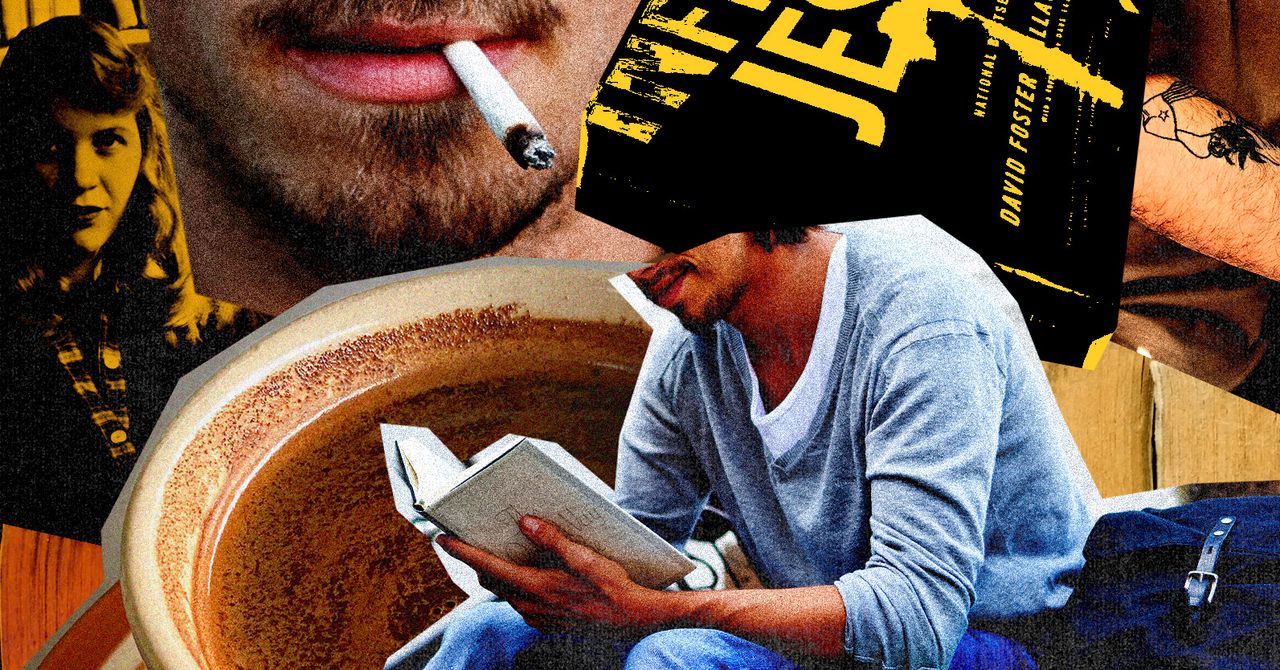

February marks the 30 years since the publication of Wallace’s magnum opus, Infinite Jest, which publisher Back Bay Books is celebrating with a new paperback edition. It is a strong candidate for the definitive American novel of the ‘90s.

A massively scaled epic (it clocks in at 1,079 pages, including 96 pages of “Notes and Errata”), the novel follows Hal Incandenza, a pot-addled teenage tennis prodigy, and a gaggle of other characters living in a near-futuristic North American Superstate, where the US, Canada, and Mexico have been congealed into the Organization of North American Nations. The marking of time itself has been subsumed by corporate interests, and companies bid for the naming rights to calendar years. (The bulk of the novel unfolds in the “Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment.”) The book takes its title from a plot-driving video cartridge deemed so addictively entertaining that it can effectively hypnotize and kill anyone who watches it.

Volleying between arch irony and deep sincerity, Infinite Jest draws from a wealth of literary and pop cultural wellsprings. Homer, The Bible, Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky, Joyce, DeLillo, William James, The Beatles, the Alcoholics’ Anonymous “Big Book” manual, M*A*S*H*, and the Nightmare on Elm Street movies are all, somehow, woven together. It is a kind of mega-text. And it spoke directly to generations of readers. Or, at least, to generations of certain kinds of readers.

Infinite Jest is formidable. It is very thick. And—with its endnotes, high-minded vocabulary (quick: define “deuteragonist,” “brachiatishly,” or “kyphotic”), tricky narrative structure (the story’s climax is sneakily hidden in its very first chapter), and winding sentences, the longest of which runs some 600-plus words—it is also conspicuously “difficult.” Merely completing the book has become something like a literary merit badge. It has also, arguably, been a key text for a breed of reader who wears such badges with obnoxious pride. A type of reader who has himself become the stuff of mockery, misgiving, and near-infinite jest: the widely, and perhaps unfairly, maligned “litbro.”

“I’m not what you might consider Infinite Jest’s target demographic,” writes author and songwriter Michelle Zauner in her foreword to the newly struck 30th anniversary edition.

Zauner, best known as frontwoman of the band Japanese Breakfast, was initially egged to read the book by a guy she knew from school: “a notorious plagiarizer who used to pawn off Kerouac passages as his own in the school papers.” Litbro central casting, in other words.

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews