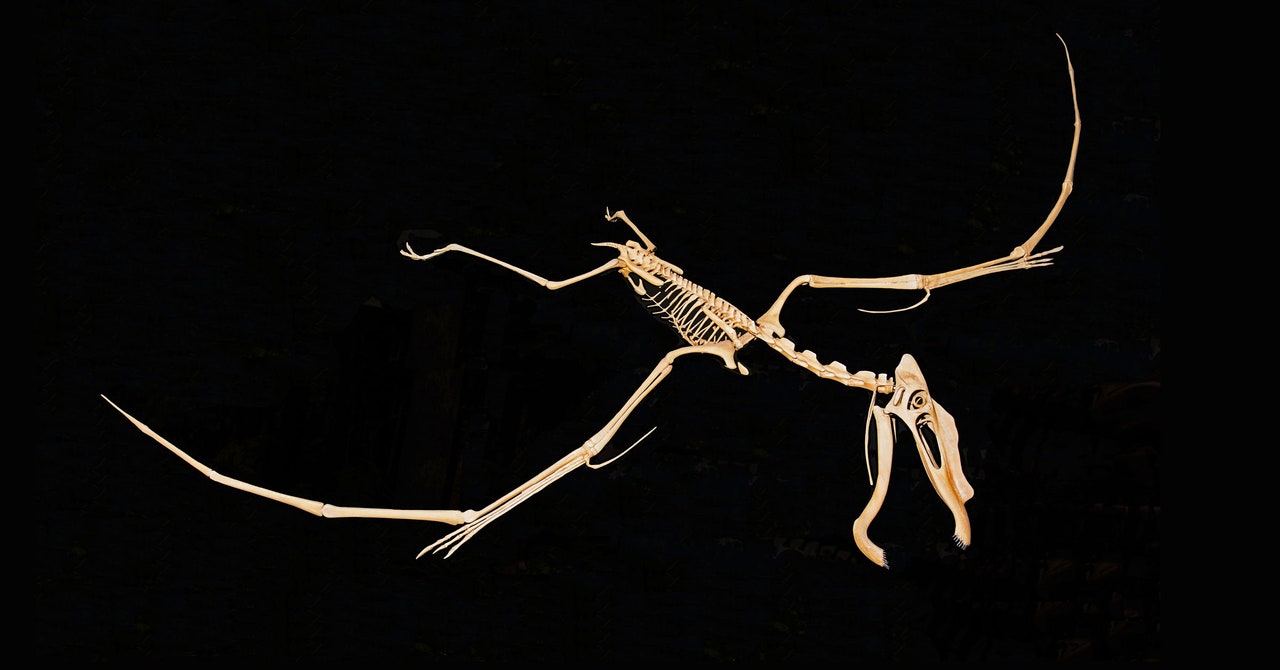

The pterosaurs had no way of knowing it, but they would one day become a bit of a headache for scientists. The flying reptiles lived alongside the dinosaurs between 210 million and 66 million years ago, ranging from the size of a sparrow to the height of a damn giraffe in the case of Quetzalcoatlus northropi, whose wings stretched 33 feet.

If they flew like birds but were in fact reptiles, which group did they take after when it comes to diet? Paleobiologists often look to living animals for clues: A Komodo dragon, for instance, packs serrated teeth for slashing through flesh, whereas crocodilians use their peg teeth to grasp prey and swallow it whole. So even though the pterosaurs are long gone, today scientists can analyze the shapes of their skulls and teeth to suggest whether a certain species was likely to hunt insects, fish, or the flesh of terrestrial animals.

Now, one group of researchers has a newfangled tool for divining not only what a pterosaur ate, but how that prey, in a sense, bit back. It turns out that chewing on different materials creates characteristic patterns of “microwear” on the tooth, on the scale of millionths of a meter. (The same thing also happens to your teeth, and to modern reptiles like crocodiles and monitor lizards.) These patterns offer clues to an animal’s eating habits.

Writing today in the journal Nature Communications, the researchers describe how they imaged the teeth of pterosaurs using a fancy technology called infinite focus microscopy, which measures in three dimensions. Then they compared the teeth to those of modern beasts, whose diets we know in great detail. They found that between all the species of pterosaurs they examined, there wasn’t much that the ancient animals didn’t eat, giving the scientists new insights that skull and tooth morphology alone could never provide. “We found carnivores, we found piscivores—fish eaters—and also invertebrate eaters,” says paleobiologist Jordan Bestwick of the University of Leicester and the University of Birmingham, lead author on the new paper. “We found pterosaurs that might have been eating slightly softer insects, so a similar hardness to dragonflies and crickets, and then those who might have been eating more crunchy items along the vein of crabs, beetles, and snails.”

They could also see how the group’s dietary preferences changed throughout tens of millions of years of evolution, painting a more vivid picture of the roles pterosaurs played in ecosystems all over the world. The researchers even unraveled clues as to how an individual pterosaur’s diet may have changed as it grew up.

Prior to this new work, paleobiologists had a few ways of resolving the diet of pterosaurs. For one thing, a few rare fossils have some soft tissues preserved, so scientists can look inside their stomachs for bones and fish scales. Fossil pterosaur feces, known as coprolites, also help. And the fact that so many pterosaur fossils are found in what were once coastal environments is a solid clue that they ate fish and other seafood.

But Bestwick and his colleagues could pick apart the pterosaur diet like never before thanks to the infinite focus microscope, which bombarded each pterosaur tooth with photons and measured how long it took for them to return to the device. A photon hitting the bottom of a groove in the tooth texture takes ever so slightly longer than one hitting a peak. They then ran this data through software that engineers use to determine the smoothness of machined parts, giving them a quantitative measure of the roughness of pterosaur teeth.