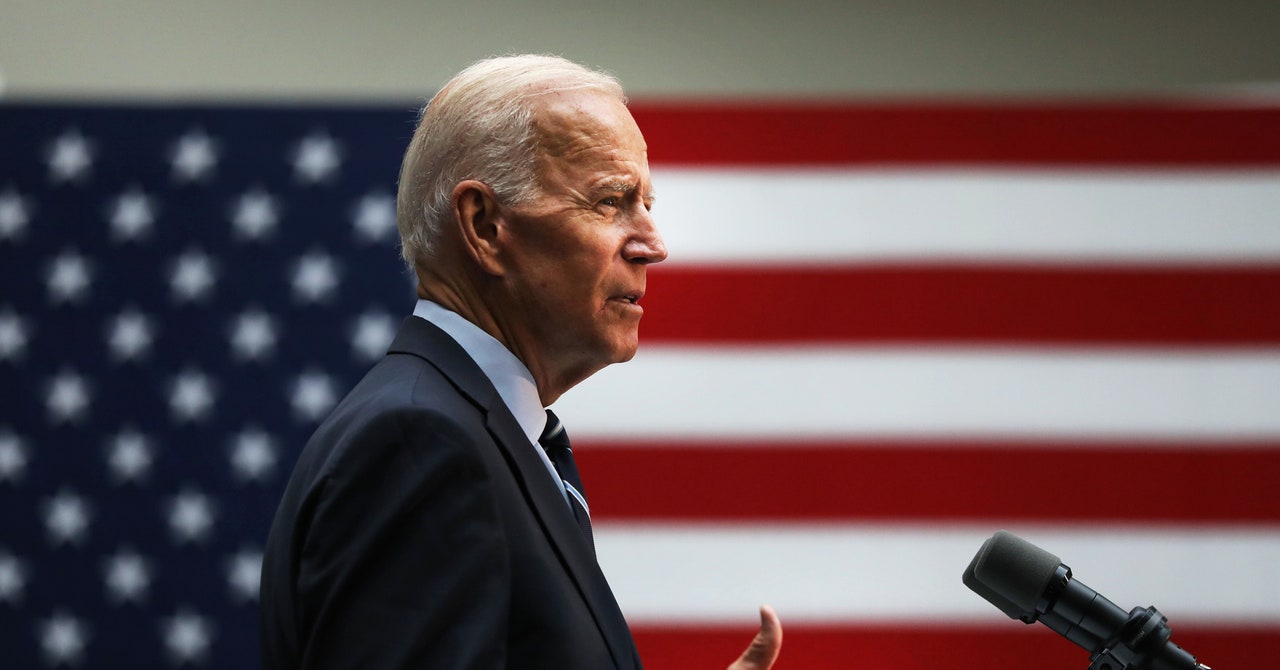

Aides to president-elect Joe Biden and vice president–elect Kamala Harris have already begun work on a presidential transition, even if the Trump administration only tries to obstruct that process. Coming out of four years of chaos and disarray, of elected and appointed officials eroding democratic norms and institutions, of a White House that has enormously damaged and abdicated US leadership on the world stage, there are innumerable domestic and foreign policy priorities. Perhaps first and foremost is getting the Covid-19 pandemic under control. Because digital issues compose a mere fraction of the bigger picture (albeit woven throughout), they must be understood in this context, too.

Long gone are the days when technology policy could be considered niche and divorced from politics. Any reinvigoration of US leadership on technology policy will exist in a world of populism and fragile democracy, of unregulated American technology giants, of authoritarian countries wielding technologies once hailed as freedom-spreading to further their own repressive ends. The Biden administration’s tech policy must therefore draw on alliances abroad—but also on a foundation of tech regulation at home.

Donald Trump has dealt profound damage to the United States’ alliance system; though well known, it’s hard to overstate. The now-lame-duck president appeared to view global partnerships not even as a means to an end but as useless altogether, continually doubling down on his “America first” behavior despite signals that it was terribly received and causing serious harm. (The exception, of course, being the relationships he saw as personally beneficial.) A senior European diplomat recently told Reuters, “The transatlantic relationship has never been this bad.” They added: “It can be repaired, but … I’m not sure it will be the same.”

Failures of coalition-building were prominently on display throughout Washington’s campaign against Chinese telecom Huawei. The (correct) claim was that Huawei’s supplying of 5G infrastructure poses cybersecurity risks, but the administration’s execution betrayed this very idea, as Trump himself offered that he could interfere with a Huawei executive’s prosecution in exchange for trade concessions from Beijing. National security was but a personal and political pawn. Trade policy and national security, too, were increasingly blurred together.

Combined with the administration’s wrecking of alliances in general, White House officials remained utterly incapable of convincing longtime allies and partners, many of whom shared concerns about Huawei equipment security, to follow the US’ lead to ban Huawei equipment from 5G networks. From the United Kingdom and France to Canada, India, and South Korea, other countries expressed remarkable aversion to following the US’ prescriptions. Diplomats may have tried, but the political powers-that-be ripped the rug out from underneath them. This is all without even attempting to misuse a word like “strategy” to describe a process that had no real strategy whatsoever. In late 2019, for instance, I attended a conversation with a senior adviser to the Trump administration on intelligence matters. When asked about the Huawei endgame—OK, so the US government convinces others to ban Huawei equipment, and Huawei 5G tanks; then what—the individual just shrugged. In reality, when that approach didn’t work, the Trump administration began threatening allies. So much for thinking ahead with complexity.

This is precisely why the incoming Biden administration, which emphasized multilateralism throughout the campaign, must found its global technology policy on alliances as well. Relations with allies in the EU and across Asia, for example, are pivotal to coalition-building on technology issues like data governance. American policymakers should harbor no illusions that the US will suddenly find total symmetry with the likes of EU member states on data privacy, say, but a renewed US global tech policy should still be founded on productive dialog, on real diplomacy, on recovering and restoring international partnerships.