March Mindfulness is a Mashable series that explores the intersection of meditation practice and technology. Because even in the time of coronavirus, March doesn’t have to be madness.

“Time Machine,” the wannabe screenwriter wrote.

It was 1985, and Danny Rubin was an ambitious improv artist in Chicago, stuck freelancing for local TV. He was taking three days off to brainstorm his ten best ideas that could take him to Hollywood. “Time Machine” wasn’t the most original title, not in the year of Back to the Future. The premise was more promising. “A guy is stuck in a time warp that commits him to living the same day over and over and over again,” Rubin wrote. “What are the different ways you can spend the same day?”

Rubin had no idea (literally none, since he shelved it and wrote two other screenplays first) that he’d just brainstormed the idea for the script that would come to define his career, Groundhog Day. In 1985, in the happy state of Beginner’s Mind, he had no clue that his concept would become a cultural touchstone. No idea that 36 years later, in a year of global pandemic, millions would feel like they too were living the same day over and over and over.

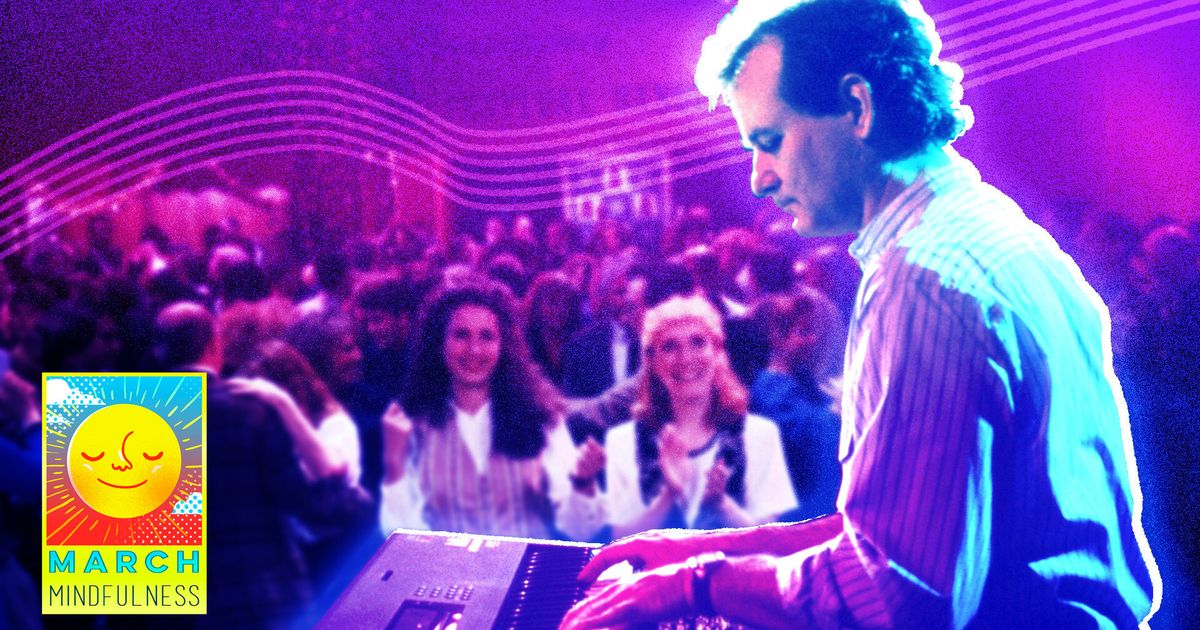

A lot of online ink has been spilled about Groundhog Day, this year especially. Much of it attempts to answer the nerdy question of how many times we see weatherman Phil Connors (Bill Murray) repeat the same day in the tiny town of Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania. (Rubin never intended a specific number beyond “more than one lifetime;” here’s my definitive list of non-definitive answers.)

But there’s something else that keeps us coming back to this 1992 classic. It’s not just the charming comedy veneer that director Harold Ramis and Murray, an improv veteran himself, layered over Rubin’s fascinating but occasionally ponderous indie movie script. Entertaining car chases are not what, according to Rubin, led Rabbis and ministers to send him copies of sermons they’d delivered about the film, or entire self-help books to be written about it, or for Buddhist priests and scholars to praise its message.

No, it’s this: Groundhog Day is the single most accessible explanation of how we can all live better when we pay attention to where we put our attention — the often-misunderstood practice known as mindfulness.

We may hear mindfulness and think “meditation,” but Phil Connors’ transformation is an object lesson in why it is so much more.

“The absolute worst day of Phil’s life took place under the exact same conditions as the absolute best day of Phil’s life.”

“The absolute worst day of Phil’s life took place under the exact same conditions as the absolute best day of Phil’s life,” Rubin writes in his entertaining annotation of the original screenplay. “In fact, a whole universe of experiences proved to be possible on this single day. The only difference was Phil himself, what he noticed, how he interpreted his surroundings, and what he chose to do.”

In his early days, selfish and frustrated, Phil chooses to blindly follow his urges. He stuffs his face in the town diner, punches the insurance salesman, and thinks stealing sacks of money will bring him happiness. He pursues meaningless sex, then plunges into an increasingly desperate infatuation with his producer Rita (Andie MacDowell). Loneliness and tedium lead him to recognize what Buddhist and therapists alike will tell you — existence is suffering — so he tries to end it.

When multiple suicide attempts don’t work, Phil’s ego explodes: I must be a god! This was Rubin’s reference to a classic Peter O’Toole movie, The Ruling Class, in which O’Toole’s aristocratic character believes himself to be the second coming. It is Groundhog Day‘s genius to take the premise one step further and say: yeah, so what? Not even thinking yourself divine can stop the endlessly repeating days from seeming eternally empty.

“He eventually is able to see other people and to see aspects of himself that had been untouched and unexplored.”

“Repetition has the power to call attention to things — to focus awareness — and it has the power to make things invisible,” Rubin writes. “Phil is able to change because eventually the endless repetitions help him become aware of things he had been blind to, even though these things surround him. He eventually is able to see other people and to see aspects of himself that had been untouched and unexplored.”

And so to the movie’s powerful final act, where Phil is finally mindful. He chooses the path of mastery after realizing that all this repetition is going to make him a master of something, even if it’s something useless like throwing cards into a hat. So he might as well use eternity responsibly, and commit to learning things that bring him, and others, delight and joy.

(This brings to mind author Julia Cameron’s response to would-be artists who complain that they’re too old to change careers: Do you know how old I’d be when I finally acquire the skills to [insert lifelong dream here]? Yes, says Cameron: “Exactly the same age you’ll be if you don’t.”)

The two pursuits that Phil decides to master both come from mindfulness. Both are art forms that were waiting in his environment, all along, to be noticed. He decides to take up the piano after actually listening to the Rachmaninov concerto that was always playing on the radio in the diner. Same goes for his slowly-acquired skill in ice sculpting: Ice sculptures made by other artists are seen in the background of shots throughout the film.

Shorn of attachment to how long mastery will take, Phil enters the zone, the much-desired state known as flow. Appropriately enough, given that the piano takes him there, it’s a very similar sensation to the one described in the recent Pixar movie Soul.

But as importantly as transforming himself, Phil starts to use his one day to transform others. He saves lives (though he cannot save the old beggar, there would have been two other deaths in the town that day if not for Phil’s actions — the kid in the tree and the groundhog grandee who needs a Heimlich). He saves a bride and groom from cold feet. He turns a run-of-the-mill groundhog night into a party par excellence. Phil is completely egoless in doing so, all sense of divinity gone. It’s simply that he has redirected attention to the most important parts of his environment: his fellow human beings.

“Every person who Phil encountered contained within them an infinity of negative characteristics (boring, stupid, smelly, poor speller, etc.) and an infinity of positive ones (funny, wise, loyal, pretty etc.),” Rubin writes. “These are all within the same person. So, which characteristics does Phil pay attention to? Again, we shape our own experience of the world far more often than we realize.”

In a sense, every day is groundhog day for everyone.

Groundhog Day has had such an incredible half-life in our culture because, in a sense, every day is groundhog day for everyone. We all wake up each morning, shackled to our bodies, repeating the same endless routines, blinking and breathing and eating and excreting. We repeat patterns, making the same mistakes, meeting the same frustrating limits to our lives, having the same fights with the same family members. The pandemic did not change any of this; trapped in our houses like Phil in Punxsutawney simply gave us more awareness of the suffering inherent in mindless repetition.

But awareness of repetition is an opportunity to be mindful. That’s the advantage of a meditation practice: It’s supposed to be boring and repetitive. You’re expected to lose focus, all the time. You go through all the cycles of suffering and doubt Phil experiences in the movie, only on a slightly faster timescale.

Through the pain and potential trauma of that process, you may just get a glimpse of your dharma — an ancient Sanskrit word that doesn’t just refer to purpose in life, the thing you can master, but the entire nature of reality itself.

Tomorrow morning, you and I and everyone alive in the world will once again step into our time machines and go back to the beginning. Millions of alarm clocks will sound, whether or not that sound is Sonny and Cher. What will we notice this time? Where will we choose to put our attention? Will we connect with the purposes that truly make us feel alive? Will we see the best in our fellow humans or the worst?

That, my dear fellow Phil Connors, is entirely up to us.