Following the Big Bang, our budding Universe slowly cooled, and the first atoms took shape. Gravity gradually pulled on clumps of hydrogen and helium gas, forming the earliest stars. This era, lasting a few hundred million years prior to the large-scale formation of stars, is called the cosmic dark ages.

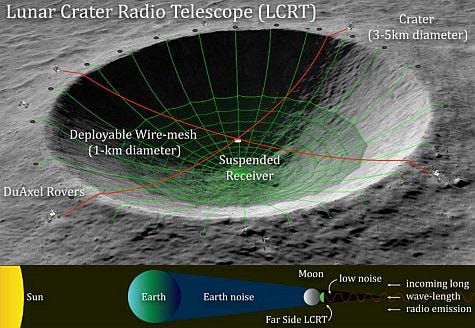

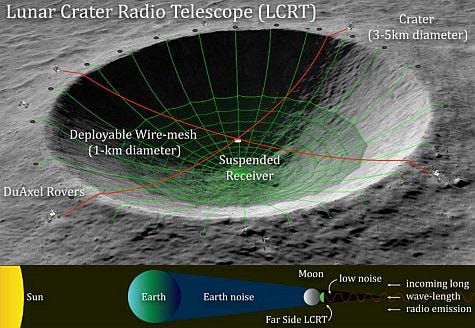

The Lunar Crater Radio Telescope (LCRT), an ambitious concept to place a massive radio telescope on the far side of the Moon, would study the Universe during this ancient era in detail for the very first time.

“While there were no stars, there was ample hydrogen during the universe’s Dark Ages — hydrogen that would eventually serve as the raw material for the first stars. With a sufficiently large radio telescope off Earth, we could track the processes that would lead to the formation of the first stars, maybe even find clues to the nature of dark matter,” explained Joseph Lazio, radio astronomer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and a member of the LCRT team.

How low can you go (in frequency)?

In 1930, a young radio engineer working at Bell Telephone Laboratories named Karl Jansky was tasked with a project to find natural sources of interference that might play havoc with communication systems of the day. A pesky signal in their readings that would not go away turned out to be radiation from the core of the Milky Way galaxy, (eventually, slowly) heralding the era of radio astronomy. Today, the intensity of radio signals from space is measured in a unit called a Jansky, in his honor.

Early work on radios focused on communications over extremely long wave transmissions. As technology progressed, the frequencies used in systems grew shorter. Today, astronomers often look at bodies over wavelengths of a centimeter or shorter. We might not think of 10 meters as being “shortwave” today, but this was the case in the time Jansky did his work, and the name stuck.

As the Universe expands, the wavelength of electromagnetic signals (like light) coming from ancient targets stretches, becoming longer. Radio signals from the cosmic dark ages are — not surprisingly — very long.

Once operational, the Lunar Crater Radio Telescope would allow astronomers to conduct extensive studies of the ancient Universe at wavelengths greater than 10 meters in great detail for the first time. These frequencies are used on Earth in VHF television broadcasts and shortwave radio.

Radio telescopes on Earth are unable to see this long-wavelength (low-frequency) radiation, as these signals are reflected back to space by the ionosphere, a layer of ions and electrons in the upper layers of our atmosphere. (This reflection also allows shortwave radios, including ham radios, to broadcast over great distances).

Human-made radio interference can also wreak havoc with sensitive astronomical equipment. Visitors to observatories with radio telescopes are asked to turn their phones to airplane mode to prevent interference with these instruments. Ultra-sensitive instruments studying radiation from the oldest stars in the Universe would need to be shielded from stray electromagnetic radiation.

“Invisible airwaves crackle with life

Bright antennae bristle with the energy

Emotional feedback on a timeless wavelength

Bearing a gift beyond price — almost free” — Rush, ‘The Spirit of Radio’

One solution — build a massive radio telescope on the far side of the Moon. With no atmosphere to write home about (OK, I wrote about it), long-wavelength radiation would fall unencumbered onto the one-kilometer (3,280-foot) collector.

The Moon itself would become an integral part of the Lunar Crater Radio Telescope, shielding the instrument from stray radiation from Earth, as well as Earth-orbiting satellites. Even radio interference from the Sun would be blocked during lunar night (which peaks as we see a full Moon).

Will we send them cheesy movies? The worst we can find? La-la-la!

As human colonies and robotic explorers become more common on the far side of the Moon, this silent spot in the solar system could experience interference from communications and scientific equipment. However, so far, only China is exploring the far side of the Moon.

Placing humans on the far side of the Moon constructing this revolutionary instrument would be costly, and entail unnecessary risk. However, robotic technologies (possibly combined with artificial intelligence) could provide a means to build the telescope at a significantly lower cost. Wire mesh for the Lunar Crater Radio Telescope could be hung by robotic construction workers, toiling away in the harsh conditions on the far side of the Moon.

“We propose to deploy a 1 km-diameter wire-mesh using wall climbing DuAxel robots in a 3–5km-diameter lunar crater on the far-side, with suitable depth-to-diameter ratio, to form a spherical cap reflector. This Lunar Crater Radio Telescope… will be the largest filled-aperture radio telescope in the Solar System!” Saptarshi Bandyopadhyay writes for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The Lunar Crater Radio Telescope is one of the revolutionary proposals named in NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts program. This program develops bold ideas, as early concepts in space exploration and astronomy are first being developed.

This article was originally published on The Cosmic Companion by James Maynard, founder and publisher of The Cosmic Companion. He is a New England native turned desert rat in Tucson, where he lives with his lovely wife, Nicole, and Max the Cat. You can read this original piece here.