Of all the questions facing astronomers today, some of the biggest unknowns are about the stuff that makes up most of the universe. We know that the ordinary matter we see all around us makes up just 5% of all that exists, while the rest is made up of dark matter and dark energy. But because dark matter doesn’t interact with light, it is extremely hard to study — we have to infer its existence and position from looking at the way it interacts with the ordinary matter around it.

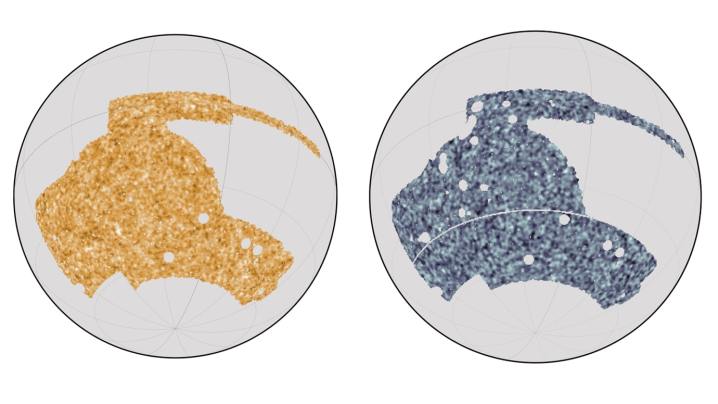

Recent research is helping in this task by producing the most accurate map to date of how both matter and dark matter are spread across the universe. Astronomers collected information from two different telescopes, the Dark Energy Survey telescope and the South Pole Telescope, to make their map as precise as possible.

For both telescope data sets, the researchers used the phenomenon of gravitational lensing — in which a massive body like a star, galaxy, or galaxy cluster warps spacetime and acts like a magnifying glass — to detect both regular matter and dark matter.

The results brought some surprises, like the fact that matter is less clumpy than would be expected based on current models of how the universe formed. It shows that the matter is more evenly spread out that predicted. If other surveys find similar results, this could indicate that there is something missing from current theories on how the universe formed in the period immediately following the Big Bang.

“I think this exercise showed both the challenges and benefits of doing these kinds of analyses,” said one of the lead authors of the research, Chihway Chang of the University of Chicago, in a statement. “There’s a lot of new things you can do when you combine these different angles of looking at the universe.”

The research is published in three papers in the journal Physical Review D.

Editors’ Recommendations

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews