Nearly 20 years ago, astronomers observed a massive cloud of fine dust particles around a young star located just 63 light-years away from Earth. In recent observations from the Webb Space Telescope, however, the dust cloud had mysteriously vanished. Now, a new paper suggests the dust cloud may have been caused by a violent event that pulverized large celestial bodies and spread their remains across the Beta Pictoris star system.

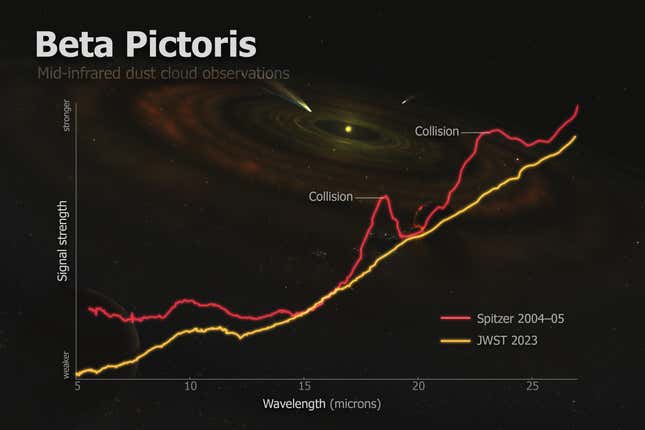

Using new data from Webb, a group of scientists spotted significant changes in the energy signatures emitted by dust grains found around Beta Pictoris, with particles that had gone completely missing. By comparing the Webb data to older observations captured by the Spitzer Space Telescope in 2004 and 2005, the scientists suggest that a cataclysmic collision between large asteroids took place about 20 years ago, which broke apart the celestial bodies into fine dust particles smaller than powdered sugar. The dust likely cooled off as it moved away from the star, which is why it no longer emits the same thermal features first observed by Spitzer. The new findings were presented Monday during the annual Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Madison, Wisconsin.

Advertisement

Christine Chen, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute and Johns Hopkins University, first observed Beta Pictoris in 2004 using the Spitzer Space Telescope. The young star system is home to the first debris disk ever imaged around another star, and is notable for being near and bright.

When Chen was given 12 hours of observations with Webb, she wanted to go back and look at the same star system, Beta Pictoris, that had intrigued her for all those years. This time, however, the star system didn’t look all that familiar. “I was like, ‘oh my gosh, the features are gone,’” Chen told Gizmodo. “Is this real? And if it is, then what happened?”

Advertisement

Through the Webb observations, Chen, who lead the new study, and her team focused on heat emitted by crystalline silicates—minerals commonly found around young stars—and found no traces of the particles previously seen in 2004 and 2005.

“Whenever astronomers look at the sky and they see something, we always assume that everything is in steady state, that it’s not changing,” Chen said. “The reason why we think that is because if you think about the particular instant that you’re looking at, that’s very short compared to how old these objects are, so we just think that the chances that you catch anything interesting are very small.”

Advertisement

That apparently was not the case for Beta Pictoris, a star system that is believed to be between 20 to 26 million years old. That’s relatively young compared to our own solar system, which is roughly 4.6 billion years old. During their early years, star systems are more unpredictable as terrestrial planets are still forming through giant asteroid collisions.

Therefore, the changes observed in Beta Pictoris were fairly significant. The dust cloud was 100,000 times larger than the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs, according to the astronomers. This suggests that the collision that may have caused this massive cloud to form likely involved an asteroid the size of Vesta, the second most massive body in the main asteroid belt that stretches across 329 miles (530 kilometers) in diameter.

Advertisement

The dust was then dispersed outward by radiation from the star, and the dust near the star heated up and emitted thermal radiation that was identified by Spitzer’s instruments. Webb’s new observations revealed that the dust had disappeared and had not been replaced, pointing to a violent collision.

Advertisement

“We think that big collisions like this must have happened in our solar system when it was of a similar age as part of the terrestrial planet formation process,” Chen said. “We can look at old terrestrial surfaces of the Moon, Mars, and Mercury and they all have craters on them, which tells us that impacts were much more frequent when our solar system was young.”

Through the recent observations of Beta Pictoris, scientists can probe whether the formation process that shaped our solar system is rare or more frequent throughout the universe, and how these early collisions affect the habitability of a given star system.

Advertisement

“If this giant collision happens and there’s a dust cloud that’s propagating outward from the star,” Chen said. “You could imagine that there’s some possibility that this dust cloud, as it traveled to the planetary system, also encountered the planets and it could have rained down dust onto their planetary atmosphere.”

More: Beyond the Planets: The Quirky Underdogs of the Solar System

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews