Sometimes, it’s difficult to account for the trajectory of a Hollywood career — to see the logic of a hitmaker’s ascendant path from small to enormous movies. What, for example, did studio executives detect in the quirky indie comedy Safety Not Guaranteed that convinced them, erroneously, that Colin Trevorrow was the right choice to take over the Jurassic Park franchise? Other times, the leap to the majors makes more sense. Just ask anyone who’s been keeping up with the filmography of Denis Villeneuve, who once made French-Canadian art movies but now sits at the helm of the biggest multiplex event of the year so far.

The rumbling bombast of Dune: Part Two did not come out of nowhere. Rather, it represents a steady upscaling of its visionary’s vision — not a left turn so much as the culmination of an approach that’s always leaned large. Watch an earlier Villeneuve movie, like his Oscar-nominated, homegrown war drama Incendies, and you can see telltale signs of an embryonic blockbuster sensibility, a muscular talent waiting to break into a new budget bracket and sprawl across the canvas of an IMAX screen. Dune is merely the fullest realization of what you could call his signature style: heavy with portent, perched on the ledge between action and horror, easy on the eyes, and serious as cancer.

Villeneuve’s voyage to the domain of Hollywood heavyweights has been as incremental as the delivery of mythological exposition in his Frank Herbert adaptations. That said, there is a major inflection point on that arc. The key moment of transition arrived in 2013, when the Quebecois director made his initial forays, plural, into English-language moviemaking. Premiering mere days apart (and screening at the same film festival, Toronto), Prisoners and Enemy were about as different as you could reasonably expect two thrillers with the same director, star, and unyieldingly foreboding atmosphere to be. But in their respective ways, both inched Villeneuve closer to the big leagues, with a vital assist from their shared headliner, Jake Gyllenhaal.

Of the two, Prisoners is plainly the calling card. Debuting at Telluride the week before Enemy but made a few months afterward, it found Villeneuve taking the Gavin Hood career path — that is, chasing an internationally acclaimed, socially “important” drama with a mainstream American thriller starring, yes, Jake Gyllenhaal. The actor plays a cop investigating the kidnapping of two little girls who disappeared down the street from their suburban Pennsylvania homes on Thanksgiving. While the detective works the case by the book, one of the girls’ fathers, played by an uncommonly intense Hugh Jackman, takes matters into his own hands, snatching up the key suspect (The Fabelmans star Paul Dano) and subjecting him to what is euphemistically referred to as enhanced interrogation techniques.

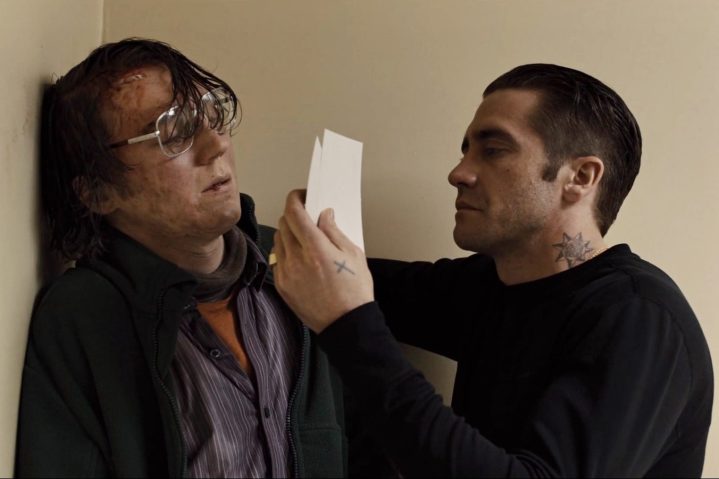

By the time Jackman’s Keller Dover has built a makeshift Guantanamo Bay in a rundown house, it’s clear that Prisoners fancies itself an allegory. How far would you go, it asks, if it was your children’s lives at stake? Two years later, Villeneuve would square ends against means again with his nightmarish, ethically murky cartel thriller Sicario. Here, the script by future Raised By Wolves creator Aaron Guzikowski fashions a blunter moral dilemma, with Dano putting an increasingly prosthetically obliterated face on the brutal realities of torture while the other girl’s parents — played by Terrence Howard and Viola Davis — stand in for a complicit America, wringing their hands on the sidelines.

The film’s conclusions about vigilante justice are critical but superficial. For all it blankets itself in a veneer of slick artfulness and respectability, Prisoners is a potboiler at heart — one that indulges in a stranger-danger fear-mongering not so different than the hysteria that drove the success of last summer’s culture-war sleeper Sound of Freedom. (No wonder this film enjoyed a second life on Netflix around the same time.) In the grimly overcast world that Villeneuve depicts, children are sitting ducks for depraved lunatics waging explicit war on God. The absurdities, improbabilities, and red herrings mount slowly until the film has all but collapsed under their weight.

That Prisoners is plenty gripping all the same has almost everything to do with how impeccably it’s crafted. Operating in the sleek crime-yarn mode of David Fincher — a little bit of Zodiac’s procedural obsession, a lot of the ludicrous falling-domino pulpiness of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo — Villeneuve envelops the audience in a sense of creeping menace and ruin so pervasive it’s practically visible. Right from the symbolically foreshadowing opening shot of a deer passing unwittingly into crosshairs, the film tightens its vice grip of predatory voyeurism. Hallways open like cavernous maws, beckoning the characters into the darkness. A lonely flute courtesy of Jóhann Jóhannsson’s sinister score sets a despairing tone, placing the events in a world hopelessly consumed by rot. As an extended mood piece, Prisoners casts an undeniable spell.

Gyllenhaal, too, is enjoyably prickly in a role that could have looked stock in other hands; there’s a certain faint levity in the exasperation that colors his detective’s brooding professionalism. It’s a better performance than the one Jackman delivers, which is so vaguely seething from the start — before the kids go missing — that there’s no shock to Dover going full Zero Dark Thirty. Gyllenhaal, workmanlike as a workaholic cop, is also better in Prisoners than he is in Enemy, delivering a dual performance of sorts as a Toronto history professor who discovers he has an identical doppelgänger — a struggling, married actor with his face and voice, but not his more reserved disposition.

While Prisoners weaves an increasingly convoluted web of plot developments and shocking twists, Enemy dawdles drowsily through a simple psychodramatic scenario. It’s a much different kind of mystery, spinning the José Saramago novel The Double into a subconscious affair. However one chooses to literally explain what’s going on (a split personality seems plausible), Villeneuve is clearly plumbing a shallow pool of sexual frustration, acting out a rather banal fantasy of a double life. Behold the fracturing mind of the domesticated man!

As in Prisoners, dread is the driving force. In fact, it’s practically the whole show in Enemy, which strikes one single note of sweaty unease — the queasy, quiet panic of shameful desires pursued — for 90 identically inflected minutes. At least Villeneuve enlivens the doomy sleepwalk with some fine supernatural affectations, like a creepy nightmare and a truly inspired final jolt, that clarify the influence of a different David, the director’s revered fellow canuck and body-horror pioneer Cronenberg.

Though it was made first, Enemy feels like the kind of oddball passion project a sleekly accessible (albeit impossibly pessimistic) thriller like Prisoners buys. Neither finds Villeneuve at the height of his creative powers or instincts. They are, again, transitional films, bridging his more resourceful, less extravagantly funded Canadian efforts to his current tenure as Hollywood’s chosen blockbuster auteur not named Christopher Nolan.

But taken together, both hint where Villeneuve would go next. In the foot and car chases of Prisoners, you can see the powerhouse clarity of his filmmaking — how he’d elevate Hollywood genre fare by rallying expert craftspeople around it. (This is his first movie with the great cinematographer Roger Deakins, who’d shoot Villeneuve’s similarly ruthless Sicario and go on to finally win an Oscar lensing his Blade Runner 2049). Enemy, meanwhile, establishes motifs that would hatch further in the sci-fi work to which he’s devoted the last few years of his career. Aren’t the abstract arachnoid visions of this more supposedly “personal” film a precursor to the tentacled alien species of his best movie, Arrival, or that briefly-glimpsed, fetish-monster spider woman in Dune?

Both films proved that Villeneuve could indefinitely ride an atmosphere of impending doom. They’re ominous front to back, never deviating from a patina of thickening disquiet. Some might call that “one-note,” and maybe they’d be right. But it’s a note this director plays with skill and holds with great control, whether he’s sending it bouncing off the moldering wallpaper of a Middle American home or echoing across the desert of an alien planet.

Prisoners is available to rent or purchase from the major digital services. Enemy is currently streaming on Kanopy and Cinemax, and is available to rent or purchase from the major digital services. For more of A.A. Dowd’s writing, visit his Authory page.

Editors’ Recommendations

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews