You wake up and something feels wrong. You can’t smell anything.

Do you have the coronavirus? You grab your iPhone, head to Google, type “I can’t smell,” and tap the first link that pops up on the page.

What you clicked was a Google Ad. From that one click, Google collects a lot of information about you — demographic data, location, and more. It also shares that data with the person who paid for the ad. In some cases, that is search marketer Patrick Berlinquette.

“With [that] data, you could see how many 45-55 year old women in Chicago who have one kid and who drive Honda are reporting loss of smell … if you needed to get that deep,” Berlinquette told Mashable in an email.

He isn’t promoting a store hawking face masks. Instead, he said he’s running Google ads to fight the coronavirus.

19K people searched from these cities in the last week.

Other Insights you’ll find: 1/10 of all searches came from Cook County, ill. (highest volume of any county). In NY: searches were conducted 2X as often by BK residents than Manhattan. 25-34 y/o women searched the most.— Patrick Berlinquette (@WarmSpeakers) April 30, 2020

Researchers around the world are using search data from Google Trends to track the coronavirus. If there is a sudden spike in searches related to COVID-19 symptoms, it could indicate an outbreak.

But there are problems with the coronavirus search data Google releases publicly through Google Trends, according to Berlinquette. He says the data is “incomplete” because you can only see “correlations after the fact.”

That’s why he turned to Google Ads. Once a user clicks on his ads, the data appears in realtime on a heat map on his website.

Google Trends only provides relative search volume. Berlinquette’s data tells you exactly how many people clicked on his search ads. He also pointed out that Google Trends doesn’t provide demographic data.

“[Berlinquette’s data] surfaces demographic information about the searchers, enabling analysis by age and gender,” said Sam Gilbert, a researcher at the Bennett Institute for Public Policy at the University of Cambridge, in an email to Mashable. “This is not possible with Google Trends.”

Gilbert, who is on the advisory board for the Coronavirus Tech Handbook, sees a number of benefits Berlinquette’s “innovative Adwords-based methodology” has over Google Trends.

“[Berlinquette’s data] surfaces much more granular geographic data than is available from Google Trends,” Gilbert continued. “This is particularly important if COVID symptom search is to be used to track and respond to spread in countries … where testing capacity is limited.”

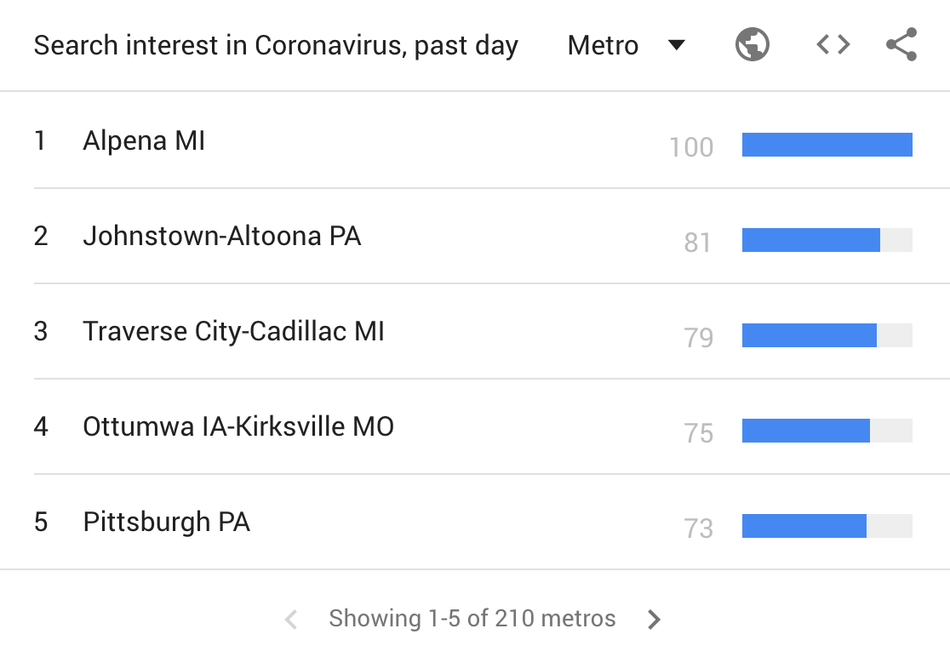

A screenshot of the coronavirus search interest on Google Trends.

Image: Google trends

Berlinquette’s current project is tracking Google ad clicks in the U.S. related to anosmia, the condition defined by loss of smell, which is believed to be a major symptom of COVID-19. He started running ads in April in 250 U.S. cities.

When a user clicks on one of Berlinquette’s ads, they are taken to an authoritative source of health information, like Healthline or the CDC, he said. Remember, the point isn’t where the users go. He just needs them to click on ads so Google can collect their data.

He then displays that data on a public website, Anosmia Google Searches. The data collected from these ads is placed on a map, and broken down in charts by city, gender, and age.

“The idea was that the data would provide epidemiologists, or anyone trying to solve the virus, a new way to find patterns, directly informed by what people are typing into Google,” he said.

A screenshot showing Berlinquette’s data with location, keywords, date, and how many times his ad was clicked.

So, what does an epidemiologist think of this data? Dr. Alain Labrique, of the Bloomberg School of Public Health and Global mHealth Initiative at Johns Hopkins University, told Mashable that the data could be useful, but too much faith shouldn’t be placed in Google searches alone.

He explained how the “gold standard” of data collection is still going into a community and testing to see “what proportion of a population has been infected or is currently infected.” Everything else is just “trying to fill in an information gap.”

Labrique noted that the biggest challenge with Google search data is bias. Who is clicking on these ads? Who is not? Do the people who do click the ads represent the the rest of the population?

“There’s been a lot of concern around what’s called super saturation,” Labrique said. “When a population is so overwhelmed by spam and advertising it’s very difficult to get a representative population to actually engage with random surveys or ads because most people are now avoiding them or blocking them.”

He also said phishing campaigns and scammers looking to take advantage of the pandemic have hindered COVID research.

“It’s been very difficult to figure out how to climb over the mountain of spam to get people to trust who you are and the information you’re looking for,” he explained.

It’s important to note that if a user performs a search on Google, but doesn’t click on Berlinquette’s ads, they’re not recorded in his data.

Labrique also recalled when a certain pop star threw off research on fevers.

“There was a term that was trending called ‘Bieber fever’ and that kept throwing off the algorithm,” he explained. “So, they had to correct it to exclude silly terms like that.”

Others have concerns about the data as well.

The most glaring flaw, as Dr. Andrew Boyd, an associate professor of biomedical and health information sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago, sees it, is how outside forces can change search behavior. He explained how national and local TV news coverage of coronavirus symptoms could affect what people search, and, ultimately, the usefulness of the data.

“There was a term that was trending called ‘Bieber fever’ and that kept throwing off the algorithm”

“Depending on what the president or the governors say, I’m assuming there’s a huge spike in search terms anytime they use any one word from vaccine to chloroquine,” Boyd told Mashable. “It’s more than just a simple spike in searches.”

“Although [this data] might provide some insight now, the question is would it provide insight during a second or third wave …” he continued. “We’re talking about a very dynamic situation … even the fact that you’re writing about this article could change people’s search behavior.”

But Berlinquette tells Mashable that he has planned for that. Before I talked to Boyd, the search marketer asked me to let him know when this piece was published for that very reason.

“I just want to make sure that I’m not dealing with an influx of clicks from people Googling ‘I can’t smell’ and clicking my ad out of curiosity,” he explained. “I don’t care about the cost, more the dilution of the data. I can do things on my end to prevent it.”

Berlinquette said that Google Ads data shows him the “word-for-word search” that led to a user clicking his ad. That’s why he doesn’t run ads on keywords such as “anosmia” or “loss of smell.”

He reasons that someone who finds his ads because they searched “I can’t smell what do I do?” is less likely to have been influenced by a news story than someone who searched “loss of smell.” So he runs ads on “I can’t smell,” “lost my sense smell,” and “when you can’t smell.”

A screenshot of one of Patrick Berlinquette’s Google search ads.

Image: Patrick Berlinquette

When asked about Berlinquette’s Google Ads methods, Labrique and Boyd both recalled a now-shuttered Google product, which launched in 2008.

“Do you remember the excitement around Google flu outbreak detector?” said Boyd, “Google had an internal team who actually was looking at search history for individuals. They were able to actually predict flu outbreaks about 24 or 48 hours before the public health departments were because everyone was googling the terms.”

Still, there is a reason that Google discontinued Google Flu Trends. Seven years after it launched, it failed to detect a 140 percent spike in cases during the 2013 flu season. Researchers attributed the miss to Google’s failure to account for changes in search behavior over time. (Some have defended Google Flu Trends, but that’s a story for another day.)

“It works, until it doesn’t,” said Labrique.”When you see a signal and it matches with what’s happening from a health context, that’s always great. But when you don’t see a signal … then what? Does that mean that nothing’s happening or does that mean that you’re just not picking it up?”

“We have to think nimbly and think of novel datasets, but we also have to remember the successes and failures of historical approaches as well,” said Boyd.

A screenshot showing the heat map on Berlinquette’s site that tracked coronavirus searches in China. The data is no longer being updated due to Google shutting down ads on those terms.

Image: coronasearch.live

Before, Berlinquette ran a similar project based on coronavirus searches in China. However, when Google deemed the pandemic a sensitive event, it only let organizations like governments and healthcare providers buy related ads, effectively killing the search marketer’s access to that data.

Mashable reached out to Google with multiple questions regarding this piece. However, the company only replied with information related to its coronavirus-related ad guidelines.

All datasets on my site are free to download. It’s early. Site’s been live for one week. But I hope this data can eventually provide new insights by city and zip as social distancing measures relax. I welcome ideas on what data would be most useful. @andrewrsorkin @samgilb pic.twitter.com/tNvCSH8XQX

— Patrick Berlinquette (@WarmSpeakers) April 30, 2020

The ads are costing Berlinquette $100 to $200 per day, which he’s currently paying for out of his own pocket. Luckily, the search marketer has a full-time job managing Google ad campaigns for 22 businesses.

So, why is Berlinquette doing this? He believes that the data he’s collecting can “predict where infections will resurge once social-distancing rules are relaxed over the coming weeks” and help prioritize where supplies should be shipped.

As for the future of this sort of data collection, Berlinquette is looking at the correlation between Google ads and drug abuse and school shootings. He’s also involved with a new pilot study at Stanford called Searching for Help: Using Google Adwords for Suicide Prevention.

“It really takes experience in marketing to know how to navigate all the mysterious rules of Google Ads,” he says. “Not only to get it up and running but to keep it approved and to ensure you’re not amassing a bunch of diluted, useless data.”

“I think this is why no one is looking at this kind of data for COVID just yet,” he continued.

As for the epidemiologist, Labrique believes some insight is better than none.

“It raises a flag that that then requires further investigation,” he explained. He also highlighted the great work Google is doing with its mobility data, which tracks movement during the coronavirus pandemic.

But Labrique thinks there is a better use of coronavirus search and ad data, like battling conspiracy theories.

“These search engines and social media platforms really have an important responsibility to help the public health by stemming the tide of what we call the ‘info-demic,'” he said. “There’s just a tremendous amount of misinformation, and also disinformation, online that the scientific community is fighting tooth and nail.”