One way to accelerate the development of a covid-19 vaccine is to conduct early testing of promising candidates on human volunteers—a prospect wrought with ethical challenges. A new policy paper outlines the ethical requirements for this type of research, but some critics believe the proposed guidelines fall flat.

Advertisement

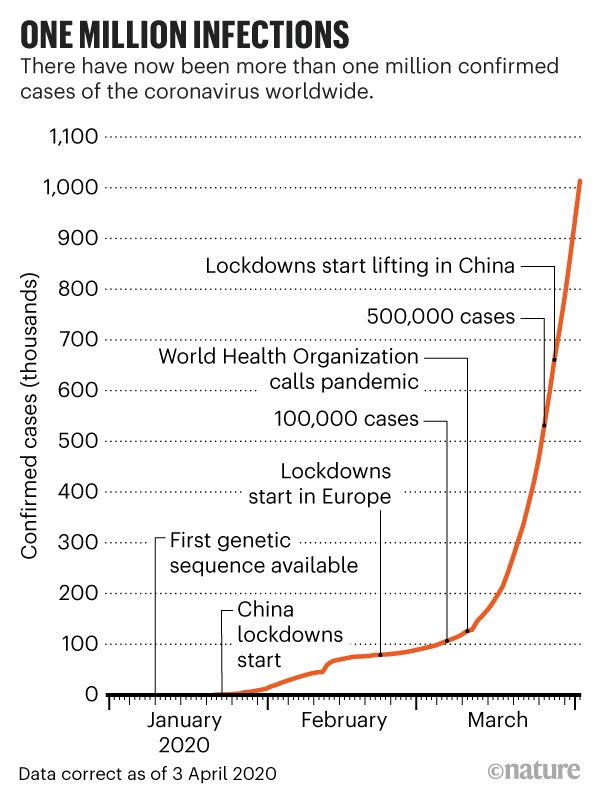

A conventional approach to drug development would result in a vaccine for covid-19 by 2036, which is clearly unacceptable. We need to develop a vaccine quickly, as the death toll and economic fallout from the ongoing pandemic continue to soar. As of today, covid-19 has killed over 264,000 people around the world, including 73,432 in the United States, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Controlled human infection studies (CHIs), also known as human challenge trials, represent a possible way for researchers to expedite development of a vaccine. For these studies, scientists recruit a small number of volunteers, who are administered a promising vaccine and then deliberately exposed to the virus. This allows scientists to run tests and collect important data in a controlled way. These studies serve as a substitute for conventional phase 3 trials, which typically involve placebos, thousands of participants, special precautions, and extended evaluations periods, among other provisions to ensure safety and efficacy.

This research technique has the potential to speed up the drug development process to a considerable degree, but it’s obviously ethically fraught. During the 2015-2016 Zika epidemic, for example, a National Institutes of Health panel blocked a proposed CHI vaccine trial, saying it presented risks and because other experimental approaches were possible. Anthony Fauci, a member of President Trump’s Coronavirus Task Force, served on this panel, as did Seema Shah, an associate professor in pediatrics at Northwestern University and the first author of a new Policy Forum article published today in Science.

In the new paper, Shah and her colleagues consider the ethics of CHIs to study covid-19. To that end, the authors put together a “comprehensive, state-of-the-art ethical framework for CHIs that emphasizes their social value as fundamental to justifying these studies,” as they wrote in the paper.

Ensure a Secure, Private Internet: The Best VPN Deals

Ethical reviews of controlled human infection studies tend to focus on acceptable risk and issues of informed consent, but the social benefits garnered by this type of research are only “assumed,” according to the authors.

“Based on our framework, we agree on the ethical conditions for conducting SARS-CoV-2 CHIs,” wrote the authors. “We differ on whether the social value of such CHIs is sufficient to justify the risks at present, given uncertainty about both in a rapidly evolving situation; yet we see none of our disagreements as insurmountable. We provide ethical guidance for research sponsors, communities, participants, and the essential independent reviewers considering SARS-CoV-2 CHIs.”

Advertisement

Due to the nature of the research, participants would have to remain in quarantine at a designated facility for an extended period of time and be closely monitored for symptoms and side effects. Researchers would keep track of key health indicators, such as blood oxygen level and the appearance of virus-hunting antibodies. Special accommodations and medical care would be available should a participant come down with the illness or exhibit other problems.

Not all of the 24 authors listed in the Policy Forum agree that CHIs for covid-19 will yield sufficient social benefits, given the risks and uncertainties pertaining to the disease and the ongoing pandemic. Still, the authors have essentially given their thumbs’ up for SARS-CoV-2 human challenge trials, so long as the conditions laid out in their proposed framework are met, including the coordination of multiple trials and related public health initiatives.

Advertisement

Considerations in the proposed framework include proving there is sufficient social value of the research, performing risk-benefit analyses, choosing a suitable site for the experiment, having reasonable criteria for selecting participants, engaging with the public and other stakeholders, acquiring robust informed consent from participants, and agreeing on fair compensation. To prove sufficient social value, researchers need to “identify and address relevant, unresolved scientific questions in rigorously designed and conducted experiments” and also ensure “equitable access to proven safe and effective” medicines, wrote the authors.

When selecting participants, for example, scientists should choose people between the ages of 20 and 29 who have no pre-existing health issues. And when acquiring informed consent, researchers need to present prospective participants with evidence-based materials and make sure they understand the risks involved, or at least, the known risks involved.

Advertisement

Indeed, it’s not immediately obvious that true informed consent is currently possible for a covid-19 study. Any vaccine trial can result in adverse outcomes, like severe allergic reactions and even life-threatening side effects, but a possible infection by the novel coronavirus could lead to serious and currently unpredictable health troubles down the road. Scientists have only been studying this disease for five months, and a grim picture is emerging about covid-19 and its ability to inflict lingering health problems, such as permanent lung damage, cardiovascular problems, and even neurological illness.

Marc Lipsitch, a professor of epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, is very much in favor of adding CHIs to our toolbox and said he was overall “quite happy” to read the new Policy Forum article. He was surprised, however, to see division among the authors on whether sufficient social value exists to justify challenge trials for research into covid-19 vaccines and therapies.

Advertisement

“There has to be an evaluation when doing challenge trials,” Lipsitch told Gizmodo, “but it seems very hard to imagine a situation where there would be limited social value.”

Back in March, Lipsitch and his colleagues wrote a paper for the Journal of Infectious Disease arguing for controlled human infection studies as a means to accelerate development of a coronavirus vaccine. The new paper is a bit different, said Lipstitch, in that such trials were evaluated based on key issues that were broken down “according to criteria the authors think are important” and “justified according to social value,” he said.

Advertisement

As for acquiring informed consent, Lipsitch said all research into new drugs involves uncertainty, and studies of covid-19 are no different in this regard. Researchers can make it clear to prospective participants that long-term effects are unknown, he said.

“We make our decisions based on the best evidence that we have,” he told Gizmodo. “More fundamentally, volunteering for a study is like serving in the army, police, or fire brigade, as those are also full of uncertainties.”

Advertisement

Kerry Bowman, a bioethicist at the University of Toronto, isn’t thrilled about CHIs for covid-19 at this time, saying the disease presents health risks and that the threshold of acceptability for a safe vaccine needs to be very high. However, “if there are ways to better understand the disease and risk, I would be more open,” he told Gizmodo.

Bowman accepts that we’re in a “profoundly complex, global health emergency, and new progressive ways of thinking and acting must be considered,” but several ethical factors require deeper consideration, he said.

Advertisement

Valid consent must be voluntary, capable, and informed, said Bowman, but the proposed guidelines in the Policy Forum insufficiently address the “informed” part of the equation.

“Months ago, the greatest risk was understood to be respiratory. Yet we now know, in an apparently small, unquantified number of people, cardiac, neurological, and possibly other forms of long-standing injury are possible, irrespective of age,” Bowman told Gizmodo. This is not accounted for, he said, in the authors’ directive to “recruit young people without underlying medical conditions who face lower mortality risks from covid-19,” as the authors phrased it.

Advertisement

Bowman said it’s unclear if any national drug regulatory body, like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, would even approve a vaccine tested through challenge trials, and seamless coordination between researchers, the teams doing the trials, and federal regulators would be needed to justify research of this nature.

“A great shortcoming of CHIs is that vaccines are different than treatments, because treatment drugs are given to a relatively low number of people, and only to those who are sick,” said Bowman. “Hundreds of millions if not billions of healthy people will need to get a covid-19 vaccine to develop herd immunity. Even if a side effect impacts just a minuscule amount of people, this could translate to a huge amount of healthy people on a global scale. In turn, a higher threshold for safety and tolerability is required in vaccines.”

Advertisement

Bowman appreciates the honesty of the authors, who admitted to divisions on the matter of social benefits, but ultimately he doesn’t think the paper presents “a sound ethical argument for moving forward.”

Advertisement

This is clearly a complicated issue with lots of moving parts, but at least we’re having this conversation, as all avenues need to be considered as we turn to the medical sciences for a solution to the ongoing health crisis.