When Russia cut off Europe’s gas supply following the invasion of Ukraine, it exposed the vulnerable underbelly of a continent largely reliant on imported energy.

To be fair, the bloc responded pretty quickly by sourcing gas from other countries and stockpiling it for a rainy day. And, it turns out, Europe was also hoarding mountains of another commodity: solar panels.

Some €7bn worth of solar panels — or 40 gigawatts direct current (GWdc) of capacity — are currently gathering dust in European warehouses. That’s enough to power 20 million homes a year.

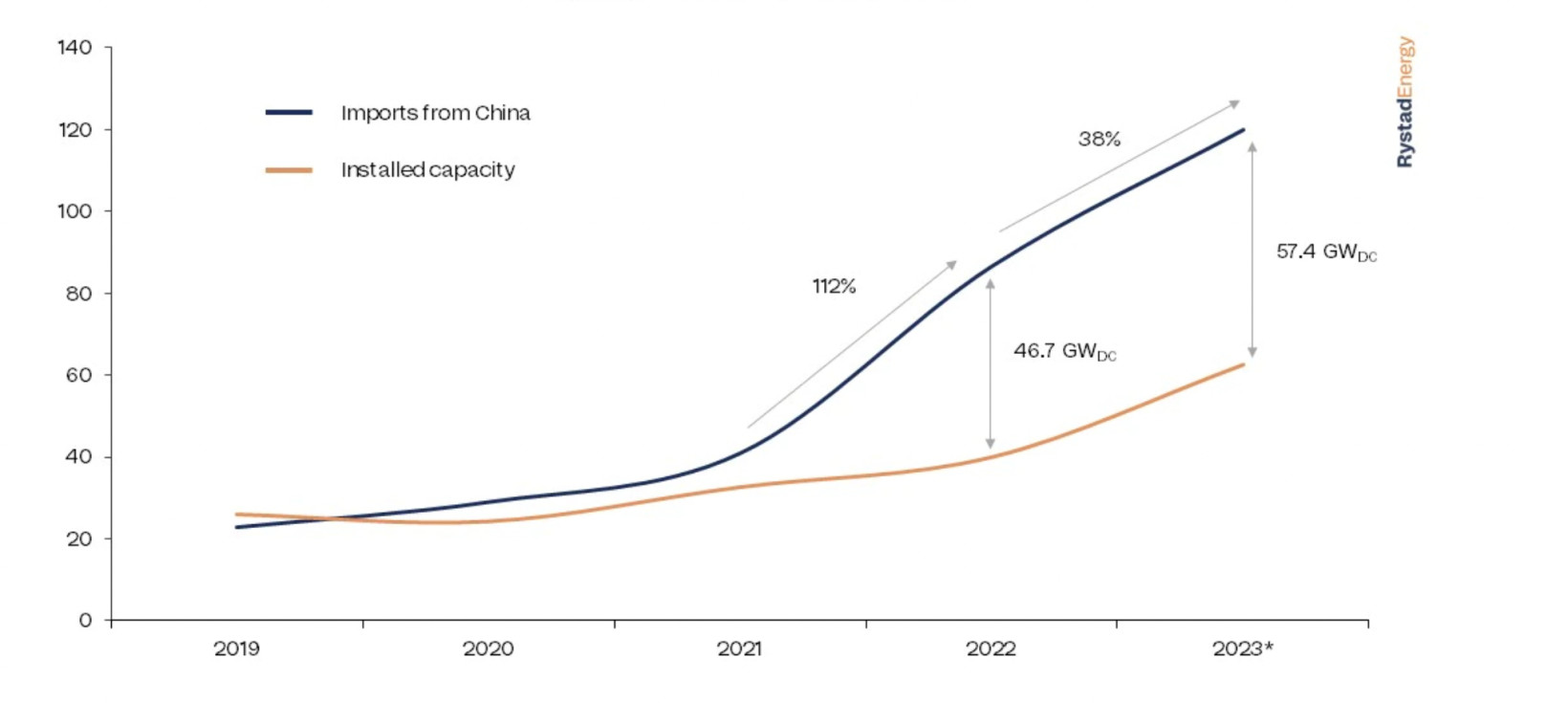

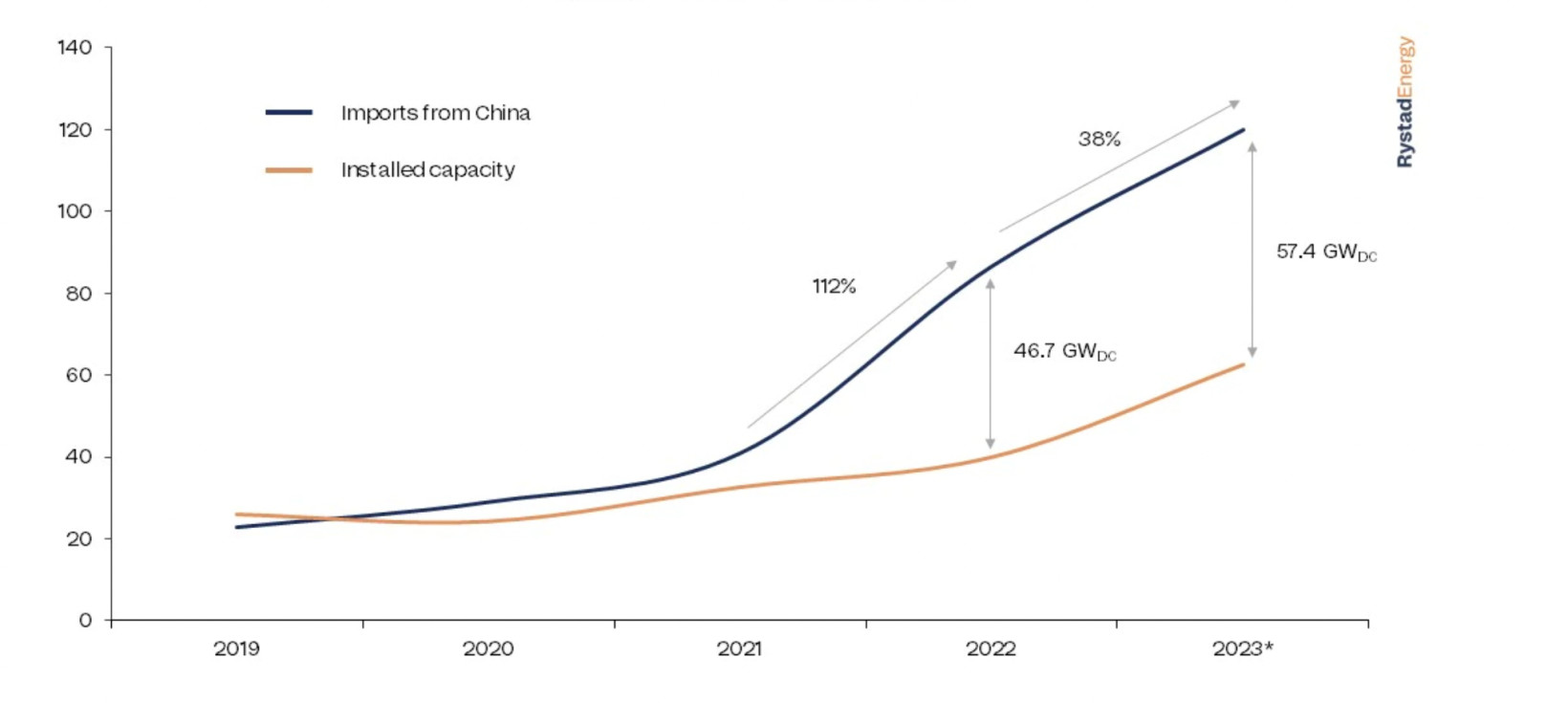

The stockpile is expected to more than double in size by the end of 2023, according to Rystad Energy, who conducted the research.

It wasn’t the war in Ukraine that drove this Black Friday-esque buying spree, however, but Europe’s green agenda.

“European countries are desperate to get their hands on affordable solar infrastructure to advance their renewable energy targets, decarbonise, and avoid paying elevated prices for new capacity,” said Marius Mordal Bakke, senior supply chain analyst at Rystad Energy.

Driven by policies like the Green Industrial Plan and RePowerEU, Europe’s spending on solar imports has almost quadrupled in the last five years, surging from €5.5bn in 2018 to more than €20bn last year.

An overwhelming 91% of this money was spent on panels from China. The Asian powerhouse produces four out of five of the world’s photovoltiacs, partly thanks to its tight grip over the building blocks of the technology — polysilicon, ingots, wafers, cells, and modules.

China’s dominance over the PV supply chain means they can offer quality panels at dirt cheap prices. Today, Chinese solar panels are up to two-thirds less expensive than those made in Europe.

A catch-22

The EU wants to source 45% of its energy from solar and wind by 2030. It also wants to produce 40% of the panels it uses locally within the same timeframe. But, currently, locally-made modules cannot compete with cheaper imports, not by a long shot.

This leaves policymakers with a dilemma: wait for domestic PV production to ramp up and risk stalling the energy transition, or import them and risk becoming dependent on China for supply. Currently, it seems Europe is opting for the latter.

“Although efforts are underway to build a reliable solar supply chain in Europe, the need for panels now means leaders cannot wait until 2025 or later to buy European,” said Bakke.

Chinese solar panels are heading to several key countries, including the Netherlands, Spain, Germany, Poland, France, Greece, Italy, and the UK.

The Netherlands, despite being the smallest country on the list, was the standout leader in Chinese PV imports in 2022, bringing in almost 45 GWdc.

Most of these countries imported far more panels than they installed. This trend is set to continue as PV installations lag behind the rate of imports due to bottlenecks such as labour shortages and material shortages.

This is not necessarily a bad thing though, as the stockpiles mean Europe has a relatively affordable source of PV modules immediately available. However, Rystad Energy does warn that if the panels stay gathering dust for too long they could become outdated and lose their value.

But perhaps a bigger concern is Europe’s increasing dependence on China for imports of solar panels and other critical materials and technologies.

“The world will almost completely rely on China for the supply of key building blocks for solar panel production through 2025. This level of concentration in any global supply chain would represent a considerable vulnerability,” the International Energy Agency warned in a special report last year.

If Russia’s invasion of Ukraine taught us anything, it’s that when it comes to energy security, don’t put all your eggs in one basket. Or as Mark Widmar, CEO of American solar manufacturer First Solar, put it: “Solar is ‘freedom energy’ — unless we depend on autocracies for the technology.”

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews