Growing up as a kid immersed in American popular culture, it’s hard to escape the impression that samurai are really, really cool. The Japanese figures—military nobility from a certain period in Japanese history, beginning in the 12th century—have been fully absorbed by American pop nerdiness and turned into infinite paragons of awesome. Supposedly honorable, supposedly undefeatable, and wearing beautiful armor, samurai are exactly the sort of heroes people love to root for: anachronistic and purportedly noble. Of course, in reality samurai are more complicated than that, a contested symbol of Japanese nationalism occupying a messy place in that country’s history and a fraught intersection of cross-cultural pollination, as the image enters the lexicon of our culture without any of the deeper political or symbolic baggage intact.

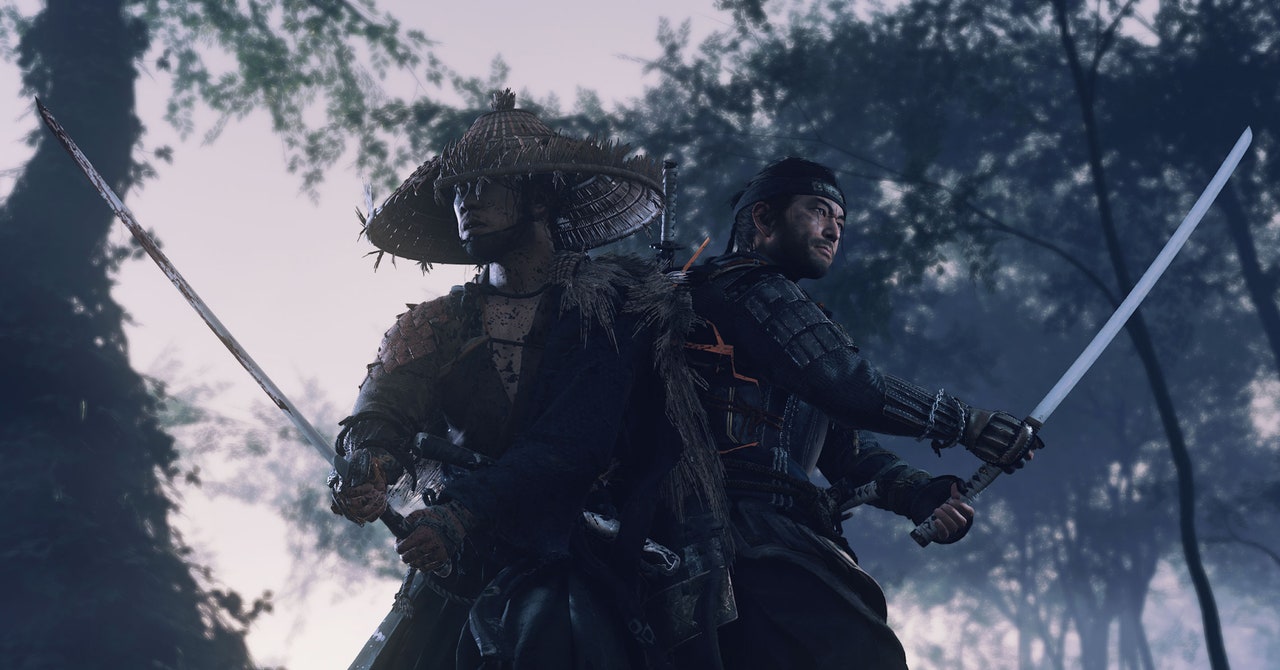

The first thing to get out of the way about Ghost of Tsushima, developer Sucker Punch’s newest open-world game about samurai, is that it’s not much interested in those cultural questions. Ghost of Tsushima is firmly a game for that American kid and the person they grew up to be. This game doesn’t think deeply about samurai, only about how cool it is when a samurai plunges his sword deeply into an enemy’s chest. Is that a bad thing? Not necessarily, depending on what you’re looking for and what your relationship to these cultural tropes is. But know going in: Ghost of Tsushima isn’t high samurai cinema. It’s a popcorn flick.

The story follows Jin Sakai, a nobleman and samurai during the first Mongolian invasion of Japan, during the 1270s. After a disastrous early battle on the island of Tsushima, Jin is left alone, his army dead, his uncle, Lord Sakai, captured. From here, he has to rebuild himself, the way videogame protagonists always do—by leveling up skill trees, capturing territory, gaining allies, and eventually fighting bosses in order to unlock more territory and … you get the idea. Along the way, he learns some ideas that are dishonorable for this pop-culture version of a samurai but traditional for a videogame protagonist—how to stab a bad guy in the back to maintain stealth, how to use an impossibly robust grappling hook, and the value of running away from guys who are clearly stronger. It’s a familiar loop of exploration, combat, and character growth that draws its roots from a decade of open-world videogames, with a samurai sheen on top.

To be fair, that samurai layer has its moments. The fighting shines, once you get the hang of it—a frantic dance of various sword stances and parries, a mixture of the sort of multidirectional big-group fights popularized by Batman: Arkham Asylum. In Ghost of Tsushima, as with Arkham, combat is almost a sort of rhythm game of moving between different opponents in mad improvisation, and a more mannered, defensive style of combat that will seem familiar for players of that other samurai game, From Software’s Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice. Unlike Sekiro, Ghost isn’t much of a challenge, but it isn’t necessarily forgiving in its fights, either. It asks that you pay attention and at least learn when to block the enemy or when to throw your (ungentlemanly) kunai to stun the heavy guys so you can go stab them in the butt. Combined with detailed combat animations that emphasize the grace and care of your protagonist’s fighting style, fighting in this game fits the fantasy. You are a swordsman beyond peer, a deadly vector with a perfect blade.

Ghost of Tsushima also has aesthetic flare. While a lot of the more granular character models and environmental textures are rather stiff for a PlayStation first-party game, it pays a lot of mind to open expanses, horizons, and color gradients. Through careful use of color and particles—cherry blossoms and leaves scattering on the breeze, little watercolor-like wisps of wind and dust—Ghost of Tsushima creates a sense of mystique and grandeur that permeates the game. So long as you don’t look too closely at, say, how your character moves through grass—by clipping wholesale through it—or get hung up on how the camera often hugs the ground in a way that actually limits your view of the horizon when you’re not on your horse, a trick that once you notice it feels like an obvious ploy to make the environment appear larger without really letting you see more of it.