This story is the first of two parts.

If you want to find YouTube videos related to “KKK” to advertise on, Google Ads will block you. But the company failed to block dozens of other hate and White nationalist terms and slogans, an investigation by The Markup has found.

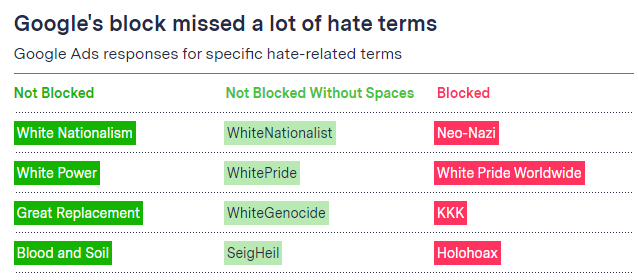

Using a list of 86 hate-related terms we compiled with the help of experts, we discovered that Google uses a blocklist to try to stop advertisers from building YouTube ad campaigns around hate terms. But less than a third of the terms on our list were blocked when we conducted our investigation.

Google Ads suggested millions upon millions of YouTube videos to advertisers purchasing ads related to the terms “White power,” the fascist slogan “blood and soil,” and the far-right call to violence “racial holy war.”

The company even suggested videos for campaigns with terms that it clearly finds problematic, such as “great replacement.” YouTube slaps Wikipedia boxes on videos about the “the great replacement,” noting that it’s “a white nationalist far-right conspiracy theory.”

Some of the hundreds of millions of videos that the company suggested for ad placements related to these hate terms contained overt racism and bigotry, including multiple videos featuring re-posted content from the neo-Nazi podcast The Daily Shoah, whose official channel was suspended by YouTube in 2019 for hate speech. Google’s top video suggestions for these hate terms returned many news videos and some anti-hate content—but also dozens of videos from channels that researchers labeled as espousing hate or White nationalist views.

“The idea that they sell is that they’re guiding advertisers and content creators toward less controversial content,” said Nandini Jammi, who co-founded the advocacy group Sleeping Giants, which uses social media to pressure companies to stop advertising on right-wing media websites and now runs the digital marketing consulting firm Check My Ads.

“But the reality on the ground is that it’s not being implemented that way,” she added. “If you’re using keyword technology and you’re not keeping track of the keywords that the bad guys are using, then you’re not going to find the bad stuff.”

‘Offensive and harmful’

When we approached Google with our findings, the company blocked another 44 of the hate terms on our list.

“We fully acknowledge that the functionality for finding ad placements in Google Ads did not work as intended,” company spokesperson Christopher Lawton wrote in an email; “these terms are offensive and harmful and should not have been searchable. Our teams have addressed the issue and blocked terms that violate our enforcement policies.”

“We take the issue of hate and harassment very seriously,” he added, “and condemn it in the strongest terms possible.”

Even after Lawton made that statement, 14 of the hate terms on our list—about one in six of them—remained available to search for videos for ad placements on Google Ads, including the anti-Black meme “we wuz kangz”; the neo-Nazi appropriated symbol “black sun”; “red ice tv,” a White nationalist media outlet that YouTube banned from its platform in 2019; and the White nationalist slogans “you will not replace us” and “diversity is a code word for anti-white.”

We again emailed Lawton asking why these terms remained available. He did not respond, but Google quietly removed 11 more hate terms, leaving only the White nationalist slogan “you will not replace us,” “American Renaissance” (the name of a publication the Anti-Defamation League describes as White supremacist), and the anti-Semitic meme “open borders for Israel.”

Blocking future investigations

Google also responded by shutting the door to future similar investigations into keyword blocking on Google Ads. The newly blocked terms are indistinguishable in Google’s code from searches for which there are no related videos, such as a string of gibberish. This was not the case when we conducted our investigation.

YouTube has faced repeated criticism for years over its handling of hate content, including boycotts by advertisers who were angry about their ads running next to offensive videos. The company responded by promising reforms, including taking down hate content. Most of the advertisers have returned, and the company reports that advertising on YouTube generates nearly $20 billion in annual revenues for Google.

In addition to overlooking common hate terms, we discovered that almost all the blocks Google had implemented were weak. They did not account for simple workarounds, such as pluralizing a singular word, changing a suffix, or removing spaces between words. “Aryan nation,” “globalist Jews,” “White pride,” “White pill,” and “White genocide” were all blocked from advertisers as two words but together resulted in hundreds of thousands of video recommendations once we removed the spaces between the words.

“This block list seems pretty naive,” said Megan Squire, a professor at Elon University studying how extremists operate on online platforms.

Among the 440 videos Google suggested for a YouTube ad campaign related to “Whitegenocide” were:

- A music video promoting the idea of White genocide that used the White supremacist phrase “anti-racism is code for anti-white.” It was posted by someone whose avatar is an anti-Semitic caricature.

- A segment from Infowars, posted by another account, accusing a European Union official of participating in a conspiracy to destabilize predominately White countries by increasing non-White immigration. YouTube banned the official Infowars channel in 2018 for repeated violations of its content rules, “like our policies against hate speech and harassment.” Earlier this year, the account that uploaded this video was also terminated by YouTube.

- A video featuring two women reciting White nationalist talking points. One of them was fired from the West Virginia Attorney General’s office for her participation in the clip.

“It’s really a question of what mistakes do you think it’s O.K. to make,” said Daniel Kelley, an associate director at the Anti-Defamation League’s Center for Technology and Society.

Google clearly has the resources to be more careful but is choosing to spend its money elsewhere, he said. “This appears to be a Band-Aid.”

In response to our investigation, Google closed the workarounds we highlighted for every term except for “Whitepill,” which remains blocked as two words but inexplicably can still be used to find videos on Google Ads when run together as one word.

Even more ad blocks

Lawton said Google has another layer of ad blocking on videos themselves that would stop advertising from appearing on hateful and derogatory content.”

“We have dedicated teams, products, and processes to find abuse on YouTube and our other platforms,” he said. “We have policies and robust enforcement in place that prohibit offensive ads and terms for ad placements on YouTube.”

However, when The Markup launched an ad campaign targeting YouTube videos that featured far-right or White nationalist content that Google recommended for “Whitegenocide,” the ad portal showed the campaign as “eligible,” which Google says means it’s “active and can show ads.”

Lawton said that description only referred to our ad, not the videos we selected—all of which “had been blocked from monetizing on YouTube for violating the platform’s policies against hate speech”—and some of those videos have now been taken down.

In the three days our ad campaign was active, the ads never ran and we were never charged—but we also never received any communication from Google saying the videos were ineligible for ads. Lawton declined to explain why an advertiser would be kept in the dark about it.

He also declined to say whether videos related to any of the other terms on our list were similarly banned from running ads—or what distinguished related videos that could not play ads from those that could. It’s clear the company is not banning ads on all videos it says are related to the hate term. We saw ads running on more mainstream videos that Google Ads had recommended for “Whitegenocide,” even after approaching Google for this story.

Authoritative sources

Videos produced by media organizations were by far the most prevalent in the first 20 suggestions from Google Ads for each of the hate-related terms on our list. The most commonly suggested videos came from CNN, the Russian government-controlled broadcaster Ruptly, and the AP Archive. Google says it ranks content from “authoritative” sources at the top of searches.

However, digging into a few overtly White nationalist terms—“White ethnostate,” “we wuz kangz” and “Whitegenocide”—we found that the proportion of offensive YouTube videos Google Ads suggested for advertisement increased as we went deeper in the search results.

An investigation by The Markup earlier this year found that Gmail and news sites using Google’s ad network ran ads for clothing emblazoned with slogans and logos for the far-right militia group Three Percenters. The ads also ran on other platforms, including Facebook, where they targeted Trump supporters and others. When The Markup reported this in January, Google spokesperson Christa Muldoon said it was a mistake and “should not have happened.” The company took down the ads.

Lawton declined to say if Google had records of any of the hate words on our list being used by advertisers to find videos for ad campaigns on YouTube.

Peter Simi, a professor at Chapman University who studies the hate movement, said the neo-Nazi group The Silent Brotherhood bought ads in far-right gun enthusiast magazines in the 1980s to recruit new members into the organization.

He said such targeting could be even more successful today.

“There’s a growing segment of the White population that’s more and more primed for these messages, especially as demographic change becomes a larger felt source of anxiety,” Simi said. “It becomes a market that you could actually identify and start to really sell things to. That’s why we buy things—we buy based on our identity.”

This article by Leon Yin and Aaron Sankin was originally published on The Markup and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.

Read next: Are wind-powered cars a reality or just science fiction?