From the time I knew what intersections were, I said my family lived at the crossing of Inwood Road and Preston Road in North Dallas. I asserted that fact certainly for the better part of a decade. Then I found out those two roads ran parallel to each other. Then we moved to a different house. I did eventually learn our new home’s location and nearest intersection. I did not, however, pass my driver’s license test until my fourth attempt, six months after my 16th birthday. My parents were not surprised. I had never been a confident driver nor a helpful passenger-seat navigator.

The month after the family Garmin GPS was stolen at a gas station was one of the most disorienting of my adolescence. I was an hour late to SAT prep class, a 10-minute drive from our house. My mother had printed directions for me, knowing there was little chance I could remember the right-left-right of the route, but I missed my exit on the highway. Suddenly, I had no idea where I was. I couldn’t spot the right offramp. I found myself adrift at 60 miles per hour until I eventually turned around.

I have always been lousy with directions and lost. My mother has a theory that my hapless navigation is the result of relying on GPS, particularly Google Maps, ever since I began driving. She’s likely right. I don’t know the way.

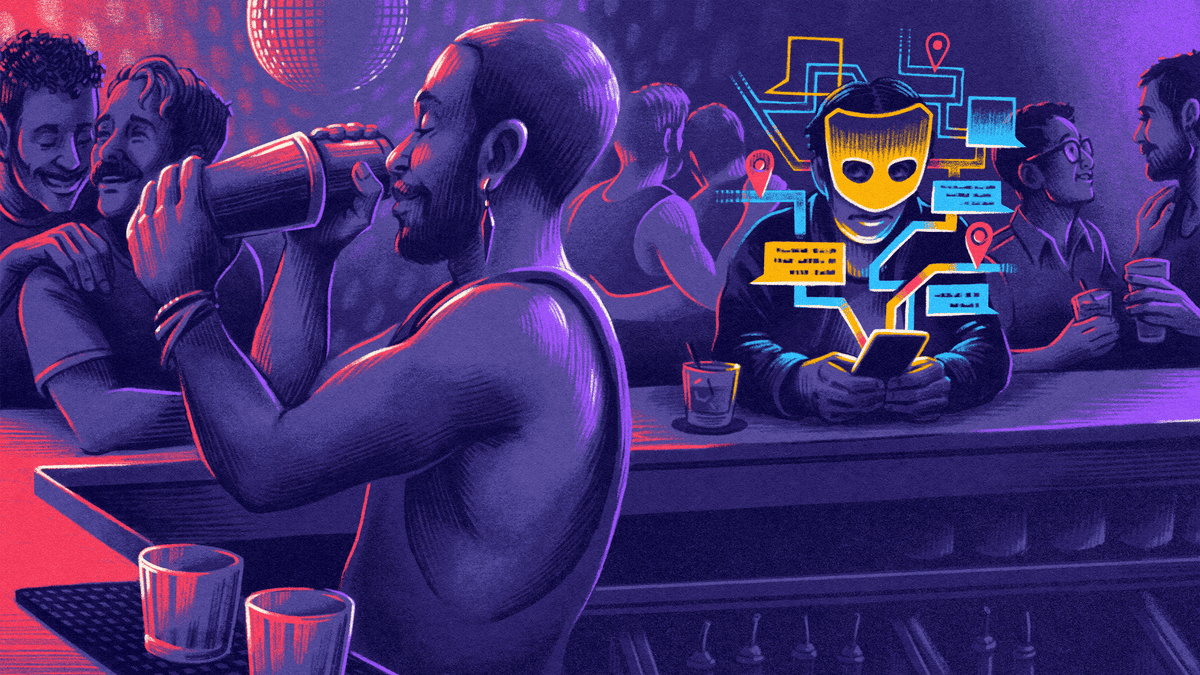

Her hypothesis holds up with regards to other tech’s effects. I do feel I’ve ceded another sense to an app—Grindr. I can’t flirt in person; talking to a man in a gay bar makes every part of me above my nipples redden and heat up with middle-school-caliber embarrassment. I struggle to bandy back and forth even with a man I know is interested in me; I would rather chat with him on the internet. There, I have no such problem. Chatting with a profile is easy, and easy to arrange a transactional meetup.

My senses of direction and seduction feel vestigial. I’m resigned to not having them; I have survived this long in their absences. I’ve become dependent on the apps that replaced those capabilities; I’ve even come to love Google Maps and Grindr. I do worry, though, that my reliance on these old technologies indicates I will surrender more of myself to new, even more powerful ones: ChatGPT and other generative artificial intelligences that write with automated ease.

When I moved to San Francisco after college, my parents asked why my cell data usage had skyrocketed, burdening the collective family phone plan and slowing everyone else’s devices. The answer was that I couldn’t leave the house without opening Google Maps.

According to my mother, my sense of direction shriveled and died because I failed to endure a prolonged period of navigational trial and error. I have always had the crutch of the digital map and its blue location pin. I was never compelled to muscle through getting lost, to learn the streets and avenues of the cities where I lived—Dallas, San Francisco, now New York City. I have little ground to argue with her. My sense of direction has not improved since my teen driving disasters. I do not know what it would be like to have it. Even now, I open Google Maps to get to my office, a place I go four days a week via train. Visiting Mexico City in April, where I could not access a map on my phone, I took long strolls—not meandering because of the romance of new surroundings but wending because I am an idiot, and I am lost.

Research shows I’m not alone. A 2017 study in Nature Communication by University College London researchers showed increased activity in the hippocampi of London drivers who did not use navigation apps compared to those who did. More connections lit up the brains of the GPS-free drivers. In a 2021 study in Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives rating navigation with a paper map vs a digital one, researchers from Ben-Gurion University found that the analog group fared better with “orientation, landmark recognition, and route recognition.” Bolstering these studies’ conclusions and my mother’s argument: It simply feels true that outsourcing navigation from our minds to our devices would lead to brain atrophy. It follows a sensible, if-A-then-B logic.

In perhaps the most direct analogue to my mother’s theory, a 2008 study out of Japan and published in The Journal of Environmental Psychology compared GPS-assisted navigators to those with “direct experience of routes,” i.e. people who had walked the streets before. Perhaps they got lost and learned their way as they did so. The assessment of the digital map followers is bleak. Not only did GPS users travel longer distances and make more stops to get to the same places as their counterparts, they “traveled more slowly, made larger direction errors, drew sketch maps with poorer topological accuracy, and rated wayfinding tasks as more difficult than direct-experience participants.” I can relate.

A similar online erosion plagues my sense of flirting, my attempts in-person seduction. They are ham-fisted and humbling. Grindr is the culprit, I feel and I fear. It has had a similar effect on me as navigation apps. Instead of a shriveled sense of the right way to drive, though, my clumsy in-person flirting may be chalked up to the omnipresence of the gay app and its hookup-oriented siblings. On a recent Saturday, I sat by chance next to a beautiful man I didn’t know in the outdoor patio of a gay bar in Williamsburg, The Exley. He introduced himself as everyone was instructed to go inside at midnight like a gaggle of Cinderellas. As I pulled my hand away from his shake, he gripped it tighter, held it for a second longer. “Handsome,” he said as I turned back his way. He had wide, expressive brown eyes with a glow of green around the pupils. I believe I blushed, though that may be giving myself too much dramatic credit. Flustered, I said something boring. He answered. I don’t remember what he said. We returned to our groups.

I had failed to accept his invitation, to press the advantage. I hoped we might exchange another handshake—and maybe spit. I didn’t know what to say other than that. I considered seeking him out but didn’t. I followed my friends to the next bar. There would be time enough to flirt with him later via Grindr’s grid of profiles, I thought. He would be there, I was sure. We were all there. When I opened my phone on the walk home, though, he was not. I have not seen him since.

Grindr’s founder predicted how my night would go in a 2016 interview for Time Out Hong Kong. Asked if Grindr was killing the gay bar, Joel Simkhai answered, “I think our users are still socializing in bars and clubs very well. And even if you’re in these places and too shy to come up to someone, at the bar you can still use Grindr.” Oberlin College sociology professor Greggor Mattson wrote of the interview, “More likely the app enables people to do things they already were doing. Technology rarely causes us to change our behavior.”

Two years ago, a man stood alone with me in my garage. We had spent the evening chitchatting by a fire. He told me he had missed human contact during the tense months of pandemic lockdown in San Francisco. I said I had, too. It was the end of the night. We were silent as a rideshare picked him up. I texted him to ask what he meant. “Just really wanted to kiss you, etc,” he said. What else could he have meant? Perhaps another different strain of coronavirus robbed me of this sense before it could ever develop—not smell, but this quiet and intimate way of talking.

In negotiations over an open relationship five years ago with my then-boyfriend, he nixed the possibility of either of us using “the apps.” He said he wanted to meet potential external partners in bars, in person. I told him I didn’t know how to do that. He reversed his position. Sometimes I wonder what would have happened if he hadn’t. My arms-length relationship to romance may be better suited to online interaction than in person. I am a creature of the internet. It has mediated my sexuality from the pubescent beginnings. Much as dashboard GPS arrived in my teenage driving years, I came of age with Grindr. It was my first experience of online gay life at 17.

As with my failure to learn the streets and byways of Dallas and other cities, there has never been an era of my life when I was forced to find sex in person. I did not need to go to gay bars to meet men, as my forebears did. Men have always appeared on my phone, scattered across any city, every city—always available, always a few taps away.

I am not alone, I think. Anecdotally, friends have admitted the same aversion to IRL sexual pursuit and preference for the online version. We can also read a shift towards digital gay courtship in geographic data. Gay bars are disappearing across the United States. From 2007 to 2019, 36.6% of gay bars across the United States closed, according to an analysis by Mattson, the Oberlin sociologist. Grindr launched in 2009. Perhaps, as Simkhai said, gay men are using Grindr at bars, just not gay bars. Covid accelerated the closure trend, with 15% of US gay bars shuttering from 2019 to 2021, per Bloomberg. (Some researchers dispute the notion that Grindr is killing the gay bar.)

As much as I hem and haw, I live in a city with infinite party choices every night of the week, many that make sex available without any pretext. When I talked about the conceit of this essay to a friend, he advised me to go to a sex party or at least a bar with a dark room. These places have intimidated me in the past, but they could, in fact, be the cure to the disconnect I feel. The rift between IRL chat and Grindr chat may loom large in my mind, but it surely doesn’t for everyone, and it definitely doesn’t at a sex party.

Perhaps the shy inability to flirt is all in my head. It feels real enough to prevent me from trying. The idea of approaching a stranger at a bar conjures only what could go wrong, the feeling that everyone in the bar is watching and grading the interaction, the fear that if this foray goes wrong, every single one after it will, too. It is possible I would not be bad at flirting if I tried. What I do understand is that it feels much easier to chat with someone online than in person, a feeling I am ashamed of.

This is not an episode of Black Mirror; this is real life. Technology is not all bad. I would not use these apps if I did not get what I needed from them. I met a boyfriend of two-and-a-half years via Grindr, my longest relationship to date. Google Maps has allowed me to navigate thousands of routes in home cities and far-flung destinations. These technologies I am complaining about have proven enormously practical in my life. I love using them. It is only in moments of reflection—when my phone dies—that I notice the gap between what I can do with my device versus without. It feels like a cognitive phantom limb. When I need to get somewhere, though, I don’t stop to think if I should muscle through getting lost and learn the way. I’m running late.

I have accepted my own woeful navigation and awkward attempts at flirting as clunky, club-footed parts of who I am. Hardly revolutionary; I have no other option. What gives me pause in considering the effects Google Maps and Grindr have had on me, though, is watching AI creep into our lives. My reliance on them has grown inside my body like a new organ. Generative AI will not take me over from the outside; it will sprout within and engorge itself.

What senses will ChatGPT obviate in us in 10 years? In 15, as long as I’ve been using Google Maps and Grindr? In our children? A feeling of helplessness overtakes me when I get lost and my phone is dead.

ChatGPT appears to be a more powerful and wider-ranging software than either Google Maps or Grindr. The senses it could supplement and supplant seem deeper-seated than navigation or flirting. I see AI eating away at writing and reading already. College professors and high school teachers report a flood of obviously AI-generated essays. News outlets are experimenting with AI writing articles. The stories are full of errors; nonetheless, more are coming. SAG-AFTRA president Fran Drescher warned actors and writers alike in her strike kickoff speech, “We are all going to be in jeopardy of being replaced by machines.” Artificial intelligence threatens to erase a class of starter job in which journalists learn how to report by aggregating other outlets’ stories. I began my career in a role like that. These are jobs where reporters ape others to develop their own talents. The positions are not high-profile, but they are essential. These reporters deliver your breaking news to you. The bulk of their jobs is summary and rewriting, exactly the function of ChatGPT. If fledgling reporters can’t find entry-level jobs, there will be few economic stepping stones to prestigious jobs at major outlets. AI may well pull up the ladder for a class aspiring reporters. We may only realize our loss when it is too late.

In late June, Matt Shumer, an entrepreneur, tweeted, “Introducing ‘gpt-author.’ One prompt -> an entire fantasy novel! Just describe the high-level details, and a chain of AI systems will write an entire book for you in minutes.” I have been writing a novel for the better part of three years now. An AI writing a book in minutes—one that I have to believe, for my own sanity, will be of unreadable quality—is offensive to me. I am exceedingly nervous for the upcoming age that promises to automate writing. It feels cruel and unfair that we have crafted machines to do the work that exalts human creativity—writing, making images, composing music—art!—rather than remove the drudgery that comprises so much else of life. I would like an AI that fills out my health insurance paperwork, not another aspiring novelist to compete with.

Google itself, one of the world’s titans of AI, shares my worries. The company’s own AI safety experts fretted over whether their AI products would lead to the “deskilling of creative writers” in a December presentation to executives, according to The New York Times. The company is testing an AI that will dispense advice in response to users’ personal dilemmas, the Times reported. Dear Abby may not be long for this world.

“The most important issue with AI music isn’t who gets paid, but the atrophy of human learning,” the musician Grimes, who has two children with Elon Musk, said at a hackathon in San Francisco mid-August. “I don’t want my children to be guinea pigs for what happens when u raise kids around tech that thinks for them… I want them to learn how to write… Being able to read and write well deeply impacts the way you think.”

Is my feeling of pre-singularity tension well-earned or just my own anxiety? ChatGPT could become just as beneficial as Google Maps and Grindr. I might come to need it every day, maybe even anticipate doing so. Right now, though, I don’t want a bot writing in my stead. I may be forecasting doom because that is simpler than predicting some middle-ground future where AI plays a role in my life but doesn’t determine it in a totalizing, dystopian way. For some, it already does: facial recognition software is already sending innocent Black people to jail.

We draw lines in the sand to separate the useful versions of a piece of technology from the dangerous ones. Think of the continuum of uranium from nuclear power to nuclear bomb; of 3D printers from Dungeons & Dragons figurine builders to ghost gun makers; of drones from vaccine-carriers to airborne improvised explosive devices. In between these extremes lie the lines of the law and societal norms. What AI products we allow, where on the path from email writer to automated nation-state hacker we choose to delineate what is acceptable, is the choice we face now.

I wonder if ChatGPT could have written a better essay. Maybe it will replace me, or, more likely, I’ll be editing its work soon. Its power seems to be growing unchecked; its presence turns to omnipresence. I am a journalist and a fiction writer. ChatGPT threatens my occupation; editors-in-chief have said as much multiple times. I have invested enormous amounts of effort and time into improving my facility and familiarity with words. Writing brings me great joy. What will happen to it? What will happen to us?

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews