It seems like every few months, someone publishes a machine learning paper or demo that makes my jaw drop. This month, it’s OpenAI’s new image-generating model, DALL·E.

This behemoth 12-billion-parameter neural network takes a text caption (i.e. “an armchair in the shape of an avocado”) and generates images to match it:

I think its pictures are pretty inspiring (I’d buy one of those avocado chairs), but what’s even more impressive is DALL·E’s ability to understand and render concepts of space, time, and even logic (more on that in a second).

In this post, I’ll give you a quick overview of what DALL·E can do, how it works, how it fits in with recent trends in ML, and why it’s significant. Away we go!

What is DALL·E and what can it do?

In July, DALL·E’s creator, the company OpenAI, released a similarly huge model called GPT-3 that wowed the world with its ability to generate human-like text, including Op Eds, poems, sonnets, and even computer code. DALL·E is a natural extension of GPT-3 that parses text prompts and then responds not with words but in pictures. In one example from OpenAI’s blog, for example, the model renders images from the prompt “a living room with two white armchairs and a painting of the colosseum. The painting is mounted above a modern fireplace”:

Pretty slick, right? You can probably already see how this might be useful for designers. Notice that DALL·E can generate a large set of images from a prompt. The pictures are then ranked by a second OpenAI model, called CLIP, that tries to determine which pictures match best.

How was DALL·E built?

Unfortunately, we don’t have a ton of details on this yet because OpenAI has yet to publish a full paper. But at its core, DALL·E uses the same new neural network architecture that’s responsible for tons of recent advances in ML: the Transformer. Transformers, discovered in 2017, are an easy-to-parallelize type of neural network that can be scaled up and trained on huge datasets. They’ve been particularly revolutionary in natural language processing (they’re the basis of models like BERT, T5, GPT-3, and others), improving the quality of Google Search results, translation, and even in predicting the structures of proteins.

[Read: ]

Most of these big language models are trained on enormous text datasets (like all of Wikipedia or crawls of the web). What makes DALL·E unique, though, is that it was trained on sequences that were a combination of words and pixels. We don’t yet know what the dataset was (it probably contained images and captions), but I can guarantee you it was probably massive.

How “smart” is DALL·E?

While these results are impressive, whenever we train a model on a huge dataset, the skeptical machine learning engineer is right to ask whether the results are merely high-quality because they’ve been copied or memorized from the source material.

To prove DALL·E isn’t just regurgitating images, the OpenAI authors forced it to render some pretty unusual prompts:

“A professional high quality illustration of a giraffe turtle chimera.”

“A snail made of a harp.”

It’s hard to imagine the model came across many giraffe-turtle hybrids in its training data set, making the results more impressive.

What’s more, these weird prompts hint at something even more fascinating about DALL·E: its ability to perform “zero-shot visual reasoning.”

Zero-Shot Visual Reasoning

Typically, in machine learning, we train models by giving them thousands or millions of examples of tasks we want them to preform and hope they pick up on the pattern.

To train a model that identifies dog breeds, for example, we might show a neural network thousands of pictures of dogs labeled by breed and then test its ability to tag new pictures of dogs. It’s a task with limited scope that seems almost quaint compared to OpenAI’s latest feats.

Zero-shot learning, on the other hand, is the ability of models to perform tasks that they weren’t specifically trained to do. For example, DALL·E was trained to generate images from captions. But with the right text prompt, it can also transform images into sketches:

DALL·E can also render custom text on street signs:

In this way, DALL·E can act almost like a Photoshop filter, even though it wasn’t specifically designed to behave this way.

The model even shows an “understanding” of visual concepts (i.e. “macroscopic” or “cross-section” pictures), places (i.e. “a photo of the food of china”), and time (“a photo of alamo square, san francisco, from a street at night”; “a photo of a phone from the 20s”). For example, here’s what it spit out in response to the prompt “a photo of the food of china”:

In other words, DALL·E can do more than just paint a pretty picture for a caption; it can also, in a sense, answer questions visually.

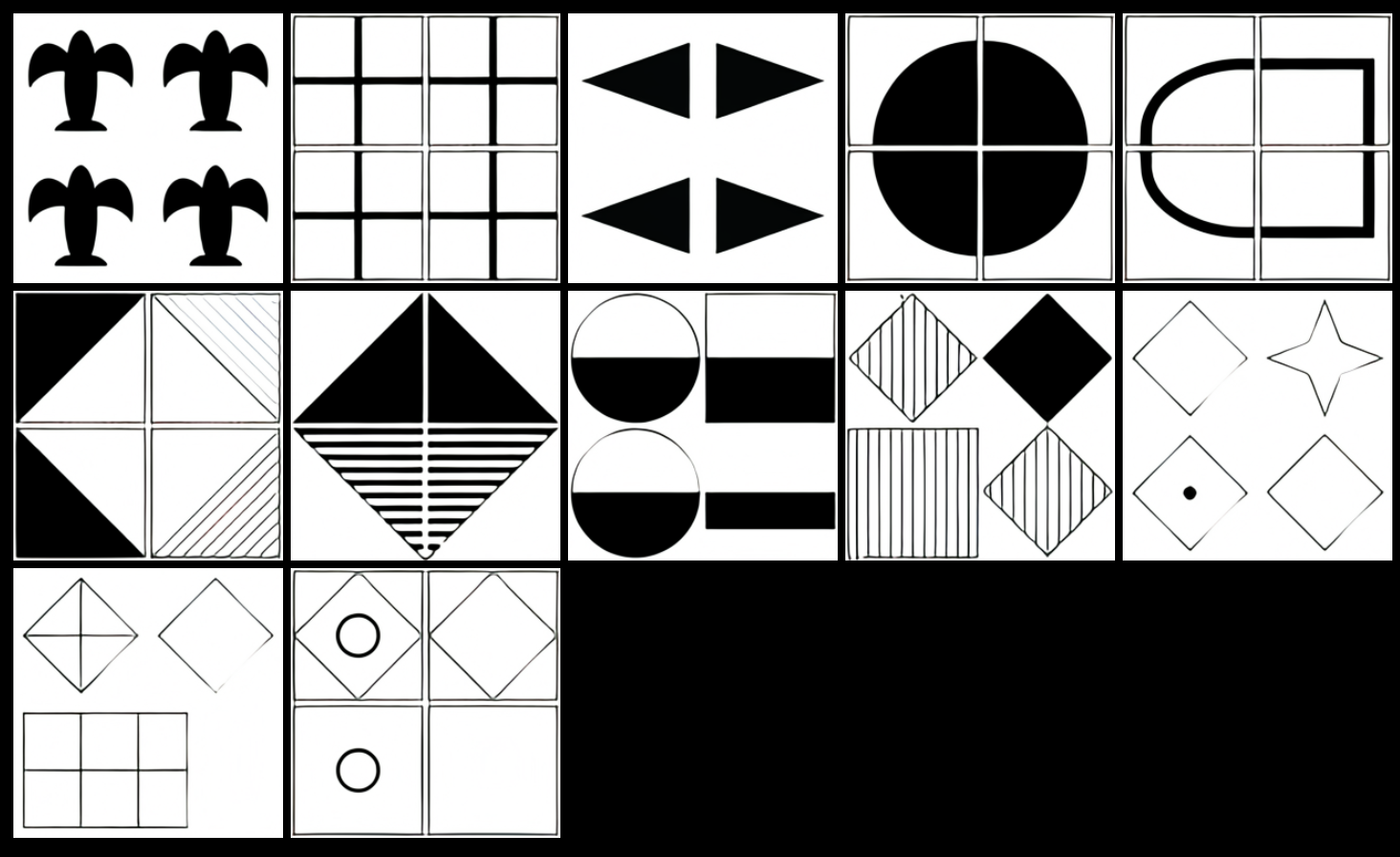

To test DALL·E’s visual reasoning ability, the authors had it take a visual IQ test. In the examples below, the model had to complete the lower right corner of the grid, following the test’s hidden pattern.

“DALL·E is often able to solve matrices that involve continuing simple patterns or basic geometric reasoning,” write the authors, but it did better at some problems than others. When the puzzles’s colors were inverted, DALL·E did worse–“suggesting its capabilities may be brittle in unexpected ways.”

What does it mean?

What strikes me the most about DALL·E is its ability to perform surprisingly well on so many different tasks, ones the authors didn’t even anticipate:

“We find that DALL·E […] is able to perform several kinds of image-to-image translation tasks when prompted in the right way.

We did not anticipate that this capability would emerge, and made no modifications to the neural network or training procedure to encourage it.”

It’s amazing, but not wholly unexpected; DALL·E and GPT-3 are two examples of a greater theme in deep learning: that extraordinarily big neural networks trained on unlabeled internet data (an example of “self-supervised learning”) can be highly versatile, able to do lots of things weren’t specifically designed for.

Of course, don’t mistake this for general intelligence. It’s not hard to trick these types of models into looking pretty dumb. We’ll know more when they’re openly accessible and we can start playing around with them. But that doesn’t mean I can’t be excited in the meantime.

This article was written by Dale Markowitz, an Applied AI Engineer at Google based in Austin, Texas, where she works on applying machine learning to new fields and industries. She also likes solving her own life problems with AI, and talks about it on YouTube.

Published January 10, 2021 — 11:00 UTC