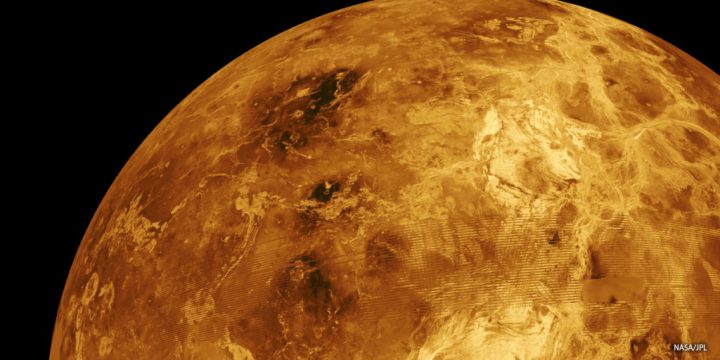

When you look at Venus today, it doesn’t seem like a very welcoming place. With surface temperatures hotter than an oven, atmospheric pressure equivalent to being 3,000 feet deep in the ocean, and no liquid water anywhere that we’ve seen, it seems like the opposite of a comfortable environment in which life could emerge.

But in the last decade, scientists have begun to wonder whether this “hell planet” could once have been habitable. Billions of years ago, Venus could have been a cooler, wetter place, with oceans not unlike our own here on Earth.

It’s even possible that a long time ago Venus could have been amenable to life — but at some point, something went drastically wrong.

To find out what it would take for our other neighboring planet to have been habitable and why it isn’t anymore, we spoke to two Venus experts about what we know about Venus’s history — and what we don’t know yet but might soon learn.

A tale of two planets

As different as the two planets are today, Venus and Earth were once very similar. The two planets are of similar size, and they formed from similar materials in the earliest stage of the solar system. They are also both within a boundary in the solar system called the snow line, which is the point at which water forms ice grains.

There are some differences — Venus is closer to the sun and therefore receives more heat, and it is less dense than Earth, and it rotates more slowly — but overall, the two planets could have followed a very similar path in their early years.

So it’s possible, though disputed, that Venus could have had water oceans in its distant past. A study by NASA planetary scientists in 2016, for example, simulated historical climate conditions on Venus and found that if oceans were present, the planet could have maintained stable temperatures of between 20 and 50 degrees Celsius for around three billion years.

But these models required that water already existed on the planet, and it’s debatable whether that was the case.

Whether or not there was water there, however, scientists agree that Venus didn’t stay comfortable. At some point, Earth and Venus diverged sharply and Venus entered what is called a runaway greenhouse phase. The higher temperatures caused the surface water to evaporate, forming water vapor in the atmosphere, which was split by sunlight into oxygen and hydrogen, which was then lost into space. Greenhouse gases built up in the atmosphere, raising the temperatures even higher. That’s thought to be how Venus became the hellish place it is today.

These changes didn’t only affect the planet’s atmosphere though. Changes to the atmosphere also affect the planet’s tectonics. With the planet’s surface heating faster than its interior, there’s less movement of material within the planet. And active tectonics, like we have on Earth, is thought to be important for habitability as it stabilizes the climate. With less tectonic activity, it could be harder for the planet to recycle water, making it less hospitable to potential life.

“We know Venus got hotter. We know it lost water. Those known losses will change the tectonics,” explained Venus tectonics expert Walter Kiefer of the Lunar And Planetary Institute. However, Kiefer said, it is also possible that there was a tectonic event that occurred first and caused the altered climate: “It’s a chicken and egg question.”

When looking at a planet’s past, Kiefer said, we need to understand how the planet operates as a whole: “We’ve got to think of Venus as a system. What was the climate doing? What was the atmosphere doing and the outgassing to the atmosphere doing? Did the tectonics drive the atmospheric evolution, or did the atmospheric evolution drive the tectonic evolution? Or more likely, some of both.”

The devil is in the timescale

It helps to be clear about what we mean when we’re talking about habitability. Because when you hear the word habitable you might think of factors from temperature to radiation amount to oxygen in the atmosphere — all the things that humans need to survive. But in planetary science terms, the word is used in a much more limited way. It refers purely to a planet that has surface temperatures between 0 and 100 degrees Celsius, where water can exist as a liquid.

“I define planetary habitability as the ability to maintain temperate surface conditions,” said planetary habitability expert Stephen Kane of the University of California, Riverside. “Meaning within a narrow range — and it is an extraordinarily narrow range — to allow surface liquid water over a long period of time.”

That’s affected by everything from magnetic fields to the size of the planet to the presence of a moon. In fact, there are a ton of factors that can have an effect on surface temperatures and no easy way to say what an ideally habitable planet would look like.

But even if conditions were perfect, and Venus did have the required surface temperatures at some point in its history, that still may not be enough for it to have been meaningfully habitable — and that’s because of the timescales required. Basically, it takes a long, long time for anything like life to emerge.

“The key to habitability is not just achieving the necessary temperature for surface liquid water, but maintaining that,” said Kane. “And maintaining it is the really, really hard part.”

It’s up for debate exactly how long a stable surface temperature is required for the emergence of life and how complex the life you’re thinking about is, but the timescales necessary are likely on the order of billions of years.

That happened on Earth, surface temperatures are maintained through processes like plate tectonics. But we frankly don’t know how common that is. Perhaps most rocky planets are like Earth, and they do have plate tectonics or other mechanisms which allow them to reach stable temperatures in the required range for long periods of time. Or perhaps most rocky planets are more like Venus, and the conditions required for life are vanishingly rare.

Our planet could be an unlikely cosmic fluke.

Relevance beyond the solar system

Given the uncertainty over Venus’s past habitability, it might seem reasonable to ask why we should even care. Even if there was a brief period where life could have emerged on the planet, the likelihood that there’s anything living there now is very low. (There are some theories that there could be microbes living in the Venusian atmosphere, but the evidence for this is hotly debated at best.)

But Venus isn’t only important on its own. It’s also representative of other planets in our galaxy.

The reason so many planetary scientists are interested in understanding Venus and its history is that it can tell us a lot about what other planets in other systems might be like. While we can’t go and visit those worlds or observe them up close, we can do that with Venus. If we want to understand exoplanets, and especially if we want to identify potentially habitable exoplanets, we need to understand the planets in our backyard first.

“Inferring the conditions for an exoplanet is going to be really, really hard. It’s a really big challenge,” Kane said. “Because it is an inference — we’re not going there, we’re not landing on the surface of an exoplanet — so the inference comes from a model.” And that model is created based on data from our solar system.

“If we’re not getting it right for our solar system, we ain’t getting it right for an exoplanet,” he said.

On the other hand, if Venus was indeed habitable at some point, then that opens the door for a large number of exoplanets to be potentially habitable too.

“If Venus did have a significant habitable period, I think that’s pretty profound,” Kane said. It may be that this is a state into which rocky planets at a certain distance from their stars naturally fall, with natural feedback loops of a water cycle that tend toward the possibility of surface liquid water. “And that would tell us a lot about whether we can expect those kinds of conditions elsewhere.”

New missions, new data

As much as we don’t know about the history of Venus, we’ll soon be learning more. With a trio of missions set to explore Venus in the next decade, we’ll get new measurements of the planet’s atmosphere and topography, and that can tell us about its history.

By looking at factors like the ratio of hydrogen to one of its isotopes, deuterium, in the Venusian atmosphere, scientists will be able to see whether the planet lost significant amounts of water over time. And by measuring the amounts of noble gases, they can learn about how the atmosphere is being swept away by solar winds and lost from the atmosphere. Other parts of the upcoming missions will uncover more information about volcanic activity on the planet and about its interior.

These three missions will take us one step closer to understanding the complex, beautiful, hellish planet next door. But wherever there are scientists, there are always more questions.

“It’ll be an additional set of clues,” said Kiefer. “Will we have all of the answers? No. We’ll come back with more missions that we need. But it’s the next set of clues.”

Editors’ Recommendations

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews