If you’ve frequented your local movie theater this summer, then you’ve surely noticed a trend among the current crop of blockbuster action films: the words “To Be Continued” popping up on the screen just before the credits roll. Cliffhanger endings in sci-fi films, thrillers, or superhero movies aren’t unprecedented, but American filmgoers haven’t seen this many movies divided in half since the boom of young adult novel adaptations in the 2010s, when the final installments of the Harry Potter, Twilight, and Hunger Games series were each split into two parts.

While each of those films openly advertised their bisected nature, some of this summer’s abrupt, yearlong intermissions are coming with little or no warning. How did this practice come to be, and why is it back with a vengeance?

A brief history of the back-to-back film sequel

Back in 1973, producers Alexander and Ilya Salkind determined that their adaptation of The Three Musketeers might not be profitable as a single, three-hour film. To double their return on investment, they cut the movie in half at its planned intermission and released it as two separate films, The Three Musketeers and The Four Musketeers a year later. This incensed the cast and crew, as they were only paid for a single production, and since then, talent contracts have been specifically worded to prevent producers from cobbling together additional movies from the footage of what was intended as one film without proper compensation.

Nevertheless, it remains more cost-effective to retain cast, crew, costumes, sets, and props for multiple films if they’re filmed either concurrently or back-to-back. As such, when a studio is certain that it wants multiple new entries in a series, it ’ll often attempt to roll the productions together. This allows it to retain talent, save on setup costs, and roll out said sequels fast, before audience interest fizzles out. This also enables filmmakers to end one installment on a cliffhanger, with the certainty that the story will get resolved in the next film.

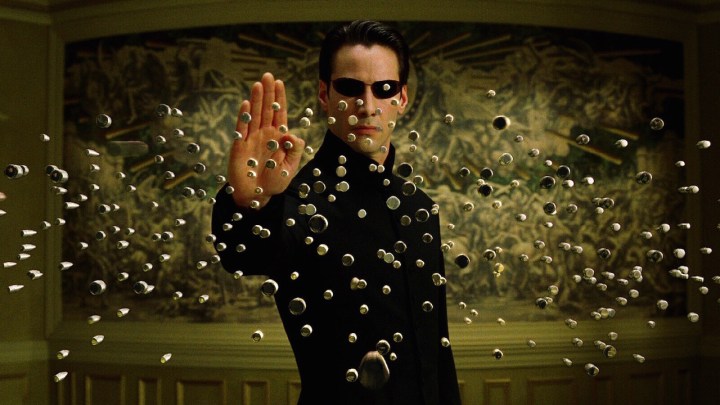

Examples of this production strategy include the second and third chapters of the Back to the Future, Matrix, and Pirates of the Caribbean franchises. However, as much sense as this all makes on paper, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who would boldly declare the third installment of any of these three trilogies to be their best. Particularly in the cases of The Matrix and Pirates of the Caribbean, the first half of these back-to-back productions became crowded with new characters and complicated ideas, which the second half struggled to resolve. At best, audiences are left with four-to-five-hour epics that don’t play nearly as well individually in theaters as they do when marathoned together at home.

After the phenomenal success of The Lord of the Rings, an entire trilogy filmed as a single production, studios got more ambitious with the long-term planning of their franchises, but they also became more dependent on them as cash cows. Harry Potter producer David Heyman claims that the decision to split the seventh and final book, The Deathly Hallows, began with screenwriter Steve Kloves, but it’s hard to imagine that Warner Bros. wasn’t begging for the chance to make an eighth film and an extra $1.3 billion. (Certainly it was dollar signs, not story demands, that convinced this same studio to stretch The Hobbit, an adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s shortest, slightest Middle-earth novel, into three films.) On the heels of The Deathly Hallows, Part 2 in 2011, the Twilight and Hunger Games franchises would follow suit, stretching the final novels of their source material into two films apiece. From a studio’s perspective, this was only logical. Why make one surefire hit when you could make two for less than twice the price?

Revenge of the two-part movie

With the foundation of the Hollywood film industry irreparably cracked by the advent of streaming and further shook by the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s no surprise that studios have doubled down even further on established properties and franchises. Each of this year’s stretched-out blockbusters gained their extended intermissions by slightly different means, but always with the pretense of a creative necessity, that the story that the filmmakers had planned was simply too epic to contain in two-and-a-half hours. Still, given the economics of it, this claim isn’t always convincing, especially since the results have varied wildly in quality.

Fast X was the first of this season’s bisected blockbusters, and easily the weakest. Every Fast franchise entry since the fifth has run past the 130-minute mark, as their stakes, stunts, and list of stars have grown out of control, but the idea that anyone would need twice that long to conclude a story about people trying to kill each other with cars is patently ridiculous. The problem here appears to be two-fold; first, if star and producer Vin Diesel is to be believed, Universal has an endless appetite for more Fast movies, even suggesting that the studio has asked for the two-part finale to become a trilogy.

Universal has yet to confirm this claim, except apparently to greenlight the Dwayne Johnson-led Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Reyes, a spin-off film set between Fast X: Part One and Part Two that may or may not be the third film Diesel was talking about. The second problem is Diesel’s inflated opinion of the depth of these films; the guy compared himself to Tolkien last year, but there’s absolutely no indication of a grand design to his saga. Johnson’s post-credits cameo promising his return to the franchise was filmed just weeks before Fast X premiered, and the movie’s cliffhanger simultaneously teases that multiple main characters may have died and that another long-dead character is actually alive. Drawing this franchise out is not doing it any favors.

On the other end of the quality spectrum is Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, the sequel to the Oscar-winning Into the Spider-Verse. It was always expected that Across the Spider-Verse would set up at least one additional spinoff (centering on Gwen Stacy), but it didn’t become the middle chapter of a formal trilogy until midway through production. In December 2021, the first teaser trailer announced that Across the Spider-Verse had been retitled Across the Spider-Verse (Part One). Producers Phil Lord and Chris Miller confirmed that their planned story had outgrown the bounds of a single film and been expanded into two, with production of the first chapter flowing continuously into the second. Months later, Across the Spider-Verse (Part Two) received its own unique title, Beyond the Spider-Verse.

While it does feature a cliffhanger ending, Across the Spider-Verse successfully justifies itself as its own film, with the final minutes establishing a new set of characters, conflicts, and stakes. One can easily see how the storytellers could, in good faith, determine that this should be two movies rather than one. This has, however, come at a terrible cost to the animators behind the film, who have been run ragged by Lord and Miller’s constantly fluctuating demands over the course of the two films’ endless production cycle.

Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning: Part One’s production has also overlapped with its sequel, though perhaps not as originally intended. Photography for Dead Reckoning was delayed multiple times in 2020 and 2021 due to outbreaks of COVID-19 among the cast and crew, and by Tom Cruise’s commitments to promote Top Gun: Maverick in 2022. Production for Dead Reckoning — Part Two began in 2021, but is still not finished filming, with the SAG-AFTRA strike putting an indefinite hold on this and every other major Hollywood production. (Among the other movies on hold? Wicked: Part One, over at Warner Bros., proving that this trend isn’t going anywhere.)

Despite Dead Reckoning: Part One not resolving its central storyline pitting superspy Ethan Hunt against an unhinged A.I., it still approximates having a beginning, middle, and end through the evolution of new protagonist Grace, portrayed by Hayley Atwell. Ethan’s battle is at its midpoint, but her origin story is complete. Only time will tell whether this investment in Grace will pay off with her taking the lead of the franchise after Dead Reckoning: Part Two, or if Tom Cruise will actually keep making these movies until he’s 80 years old.

Dune the old-fashioned way

And, finally, there’s this year’s only concluding chapter to a bisected blockbuster, Dune: Part Two. When the first of director Denis Villeneuve’s Dune films hit theaters in 2021, many viewers might have been unaware that they were sitting down for an adaptation of the first half of the iconic Frank Herbert novel. However, though it was absent from the marketing, Villeneuve did, at least, include “Part One” in the title card of the actual film, dampening the blow of its less-than-satisfying ending. This is particularly striking given that, unlike the rest of our half-movies, Dune was produced without a studio commitment to complete the duology. This makes the film’s cliffhanger less of a tease and more of a plea, since the series would only continue if the audience demanded it. We’ll find out in October whether or not Dune: Part Two can live up to that demand.

Each of these sequel strategies has a whiff of cynicism to it. The Fast franchise model operates on the assumption that audiences will gobble up new series installments regardless of their quality, while Spider-Verse and Mission: Impossible seem content to simply keep shooting/animating forever until someone stops them. One could characterize Villeneuve’s Dune strategy as weaponizing viewer outrage to extort another movie out of a studio, but this, at least, puts the power in the hands of the audience, letting us tell them what we want rather than vice versa. It’s difficult to tell if any one method of cutting a movie in half yields consistently better results, but if this release model pays off at the box office, you can bet that our study’s sample size will get a lot bigger.

Editors’ Recommendations

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews