Imagine a household where everyone logged on to the internet in the morning and spent the rest of the day online. Four hours on Zoom or FaceTime. Three hours browsing the web. Three hours scrolling through Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Three hours gaming. Four hours streaming HD Netflix. Imagine they did this every day of the month.

It seems impossible that so many people sit in front of their screens for so long, and yet something like it is a new normal in America. As work, school, and social interactions migrated online once COVID-19 became a global pandemic last March, the average monthly household data use in 2020 skyrocketed by 40 percent compared to the prior year, according to OpenVault, a global provider of broadband industry analytics. That figure includes tablet, computer, gaming console, and mobile phone data that uses a household’s broadband internet connection, but doesn’t reflect when someone accesses the internet through their cellular data. The average household now uses nearly a half a terabyte of data each month.

What exactly happens in these households when they go online is something of a mystery. The breakdown of hypothetical data usage, provided to Mashable by OpenVault, accounts for 483 GB of data by popular categories: video conferencing, browsing, social media, gaming, and streaming. It’s tempting to envision household dystopia writ large, in which families have forsaken their bonds so they can stare soullessly at a screen for nearly 20 cumulative hours a day. This is, after all, the technological fate we’ve been primed to fear.

Of course, the reality is no nightmare but a paradox. As the pandemic has proven, the internet is an essential good capable of delivering safety, connection, information, and more for those who can claim the privilege of shifting their lives online to survive a pandemic. For people who belong to marginalized communities, including rural residents, those with disabilities, and people of color, this shift created greater access to critical resources, like telemental health, grocery delivery, and local mutual aid and support programs.

Yet the surge in internet use is also likely changing us in ways that are obvious and imperceptible, that may be temporary or permanent. In the worst instances, it may unleash addictive behaviors, undermine focus and attention, influence memory, increase anxiety and dissatisfaction, heighten stress and exhaustion, and inundate people with conspiracies and misinformation that erode their trust in others — all while simultaneously making us grateful for the ability to Zoom with an old friend or schedule a parent’s vaccine appointment.

The truth is that we’re in the midst of a massive social experiment and there are few clear answers about what happens next. Experts don’t know, so users must become detectives, sorting through their digital lives for clues about how their well-being is tied to their internet use. What matters most to one’s mental health in this context, beyond standard advice about how to use the internet well, has everything to do with who you are and what you do online.

What happened online in 2020

One simple way to learn how people are faring online during the pandemic is to ask them. Last month, Mashable conducted a nationally representative online survey of 1,276 American adults ages 18 and older. We posed dozens of questions, including how many hours participants used the internet to work and pursue personal interests, if their children were in remote school, what activities they did online more frequently, and whether they felt more depressed, anxious, or fulfilled since the start of the pandemic.

Both familiar and surprising trends emerged. Two-thirds of respondents said internet capability allowed them to stay safe, and half said they would keep some of their new digital routines and habits once the pandemic is over. That included attending virtual events and activities like exercises classes, playdates for children, religious services, celebrations, and political demonstrations. A majority of respondents want to continue ordering groceries, household goods, and restaurant meals online, too. People’s desire to embrace a hybrid life, optimized for both fulfillment and efficiency, is clear.

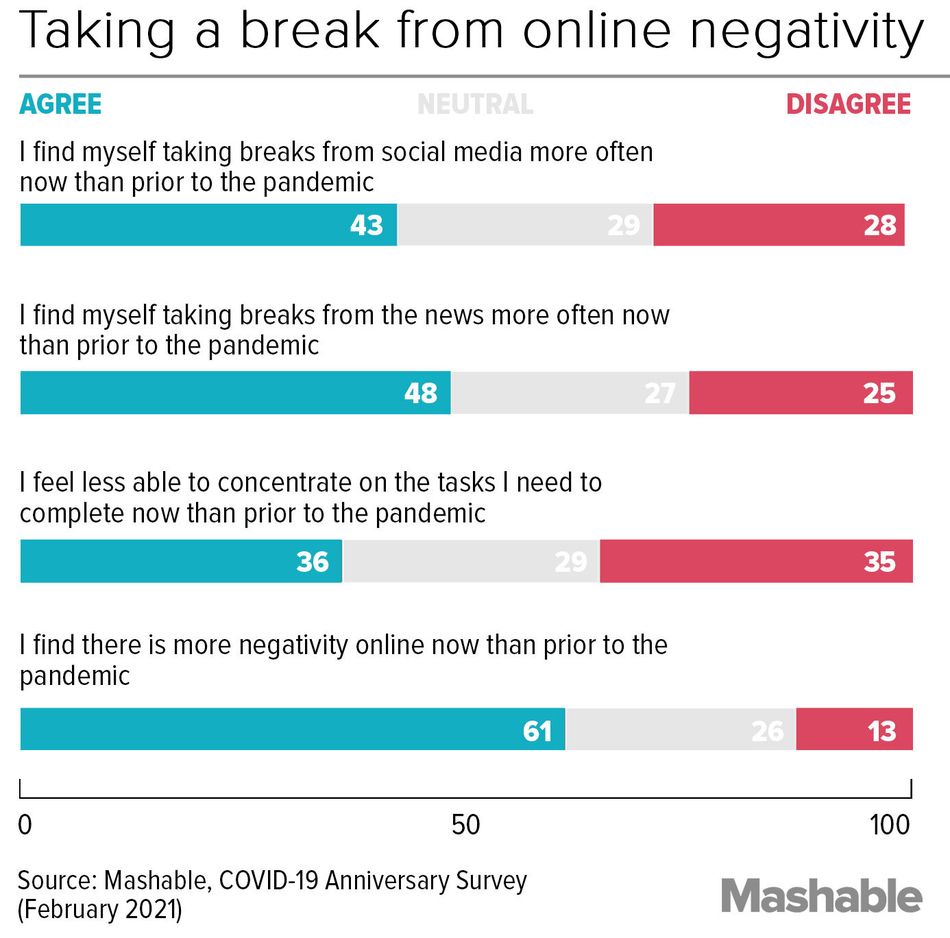

Yet there’s also a sense of unease. Sixty percent of parents said they worry about how much time their children spend online. Half of the respondents said they more frequently lost track of the hours they logged online compared to before the pandemic. Nearly a third said they didn’t enjoy spending so much time on the internet. Only 30 percent felt that virtual gatherings were an adequate substitute for the real thing. Almost two-thirds reported encountering more negativity online. More than 40 percent said they took breaks from social media more often than prior to the pandemic. Survey respondents who anonymously provided written feedback expressed disgust or disappointment over rudeness, intolerance, toxicity, misinformation, and in one case, the “very ugly side of humanity.” (For a comprehensive explanation of the survey’s results, click here.)

Image: mashable

This has always been the tension of the internet’s promise: Its tools can transform our lives, for better or worse. When we asked respondents to share how their pandemic internet use affected them, they said as much.

I feel like it has changed how I relate to people. I see people a lot less in person and find I become anxious when i do.

I find that I am lonelier now and not able to connect with others as easily.

I cherish the time I spend on FaceTime with my daughter & grandson.

[J]ust having a stable Internet has enabled me to work from home, which helps me pay the bills safely.

There are multiple ways internet use might affect our mental health, well-being, and cognitive abilities. We can connect, be heard, and exercise greater control over our lives when we use its tools to find information, opportunities, and resources. For example, the internet, along with tech savvy, has been vital for those seeking COVID-19 vaccination appointments. But we can also feel isolated, silenced, and violated when our vulnerabilities are exploited by algorithms, marketers, and other users.

Data provided to Mashable by SimilarWeb, a web intelligence traffic company, revealed that people searched for positive and enriching experiences online in 2020.

Image: mashable

After the death of George Floyd, traffic to 99 donation sites that support communities of color, like memorial funds, mental health organizations, and legal defense funds, increased by 150 percent in June 2020 compared to the previous June. The top online learning sites, which includes Coursera and Khan Academy, notched an average of 81.1 million monthly visits between March and December, a 43 percent increase compared to 2019. Worldwide searches for food donation peaked in April and remained higher than in 2019 throughout the year. Traffic to pet adoption sites shot up and stayed consistently higher. People flocked to digital therapy and meditation apps.

Trends like these are why people remain optimistic about the internet. Indeed, it’s very possible that screen time itself isn’t to blame when users feel worse. Instead, internet use ultimately supplants other activities, like exercise, sleep, and in-person socialization, which in turn worsens mood, weakens healthy coping skills, and leads to isolation.

The mirage of social media, which often prompts users to compare themselves to an idealized depiction of someone else’s life, can sometimes increase anxiety. Likes become a proxy for self-worth. Social media can similarly distort what’s happening in society as algorithms present incendiary comments and viral disputes as the norm. It’s easy to lose faith in humanity when that, and not the work of mutual aid groups, for example, is what surfaces on one’s screen every day.

Little is known about how exposure to conspiracies and hate speech online affects well-being. The amplification of that frightening trend in 2020, with the spread of QAnon and growth of far-right militias, suggests such experiences may increase anxiety and push people toward unusual thoughts and behaviors. Similarweb found that average monthly traffic to the top 20 far-right content sites, including conspiracy forum 8kun (formerly known as 8chan) and the message board TheDonald, grew by 56 percent from 2019 to 2020.

“We do have to be worried that we’ve supercharged both the good and the bad,” says Dr. John Torous, a psychiatrist and director of the digital psychiatry division in the department of psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

Image: bob al-greene / mashable

Who does well depends on who you are

Dr. Torous (and researchers like him) can’t say with certainty how a year of living online will affect people. That’s partly because there’s little research on that question.

One study conducted during the pandemic by researchers at University of California, Los Angeles and University of Cambridge found no evidence that increased online social interactions improved well-being among 119 college-age students. Instead, the researchers found lower levels of current depression when the participant’s household was larger, suggesting that direct physical contact offers benefits that virtual interactions cannot match. The preprint study has not yet been peer reviewed or published in a journal.

Previous research on screen time has also left us in a kind of limbo. Many studies collect general information from participants about what they do online rather than actively track their every move. Such research often finds an association between screen time and negative mental health effects, particularly amongst teens, but cannot prove why. For instance, it could be that lonelier, more depressed people turn to the internet for connection or stimulation, rather than the internet itself turning those people into sadder versions of themselves.

In our own survey, it was also difficult to parse how time spent online affected mental health. Thirty-two percent of respondents working 10 or more hours online actually reported experiencing better mental health during the pandemic compared to just 14 percent of all participants. It’s possible that these respondents won unexpected gains in their work-life balance, like the end of a tiring commute, increased time with children, and the opportunity to take more rewarding breaks. We don’t know why this group seemed to fare better despite their marathon online work days, and that’s partly because we don’t know enough about what they were doing on and off the internet.

Dr. Torous says that in order to better understand the complex dynamics of screen time we need a trove of data that shows exactly what people do online to make comparisons between individuals and groups of users. A cohort that spends hours a week using a therapy or meditation app might experience drastically different outcomes than a group that devotes hours to coordinating an attack on the U.S. Capitol via messaging apps.

Image: Mashable

But information with that level of detail is one of the most valuable commodities of the 21st century. It’s sold to marketers at a steep price, not given away to researchers with modest budgets. So we’re forced to make educated guesses instead.

At the pandemic’s outset, more than two dozen experts from various medical and research fields published guidance in Comprehensive Psychiatry on the perils of problematic internet use during COVID-19, and how to avoid them. (The co-authors later published an ebook on the topic). They worried about users who might turn to porn, gambling, social media, gaming, and streaming as forms of stress relief. Typically, these activities can be healthy coping strategies, but they can also lead to significant impairments for a “minority of individuals” who forego important aspects of daily living and social interactions as a result, the co-authors wrote.

“I think it’s hard to predict with 100 percent accuracy who’s going to do well and who’s going to do poorly,” says Dr. Marc Potenza, a co-author of the guidance and professor of Psychiatry, Child Study, and Neuroscience at the Yale School of Medicine. He’s most worried about people exhibiting addictive behavior online as well as those who are predisposed to it. People who are more susceptible to boredom and impulsivity may be drawn to the internet’s temptations now that usage has significantly increased. The same might be true for people who are particularly sensitive to stressors and turn to digital devices or content to alter their mood.

One finding that gave Dr. Potenza pause last year was research published by Pornhub. A snapshot of user behavior prior to the pandemic through mid-March, when COVID-19 triggered wide-scale shutdowns, revealed a spike in traffic, especially in the early morning between midnight and 3 a.m. in several countries, including the United States, South Korea, Germany, Spain, and Italy.

Dr. Potenza and two other researchers co-authored a brief article in the Journal of Addictive Behaviors about this and other insights, concerned about what might be underlying that trend, like stress and insomnia, and how that might relate to poor functioning in other parts of users’ lives. They worried that stress “in the setting of feeling powerless, hopeless, and disconnected from 12-step support systems” might lead to relapse for those who’d already been treated for problematic porn use.

In the Comprehensive Psychiatry guidance, the co-authors listed a number of habits that could prevent excessive and potentially harmful internet use during the pandemic. That advice included sticking to a schedule, sleeping regularly, eating healthy, learning relaxation techniques, regulating screen time, using analog tools when possible, and seeking help when needed. Published a few months into the pandemic, the common sense tips might have felt ambitious but worth the effort. Five hundred thousand deaths later in the U.S., many people are looking simply to survive. If the internet gives them joy or an escape, but costs them sleep or much worse, so be it.

Image: bob al-greene / mashable

The costs we don’t see

While online addictive behavior can lead to mental health crises, some potential effects of internet use are far more prevalent. It can alter our ability to focus, shape our capacity for memory, and change how we interact with others. In 2019, Dr. Torous co-authored a review in World Psychiatry about how the internet may be changing our cognition. The paper explains the paradox of the internet that we’ve come to know well at this point.

Internet access can streamline life for maximum efficiency. Yet relentless online multitasking can train our brains to look for distraction, making it more difficult to focus whether we’re on the internet or off. Some research shows that even brief interactions in an “extensively hyperlinked online environment” like online shopping can reduce attention for a sustained period after coming offline. In other words, while ordering groceries via an app for pickup or delivery means skipping a two-hour trip to the store — and provides a level of safety during a pandemic — there may be costs that are difficult to detect.

Another advantage of the internet is that we don’t need to remember facts anymore because we know where to find them online. Dr. Torous says this cognitive offloading means the brain is theoretically freed up to focus on more meaningful tasks or activities. Still, there’s evidence that people overestimate what they know as a result, mistaking their ability to locate information for authentic knowledge of a subject. This isn’t necessarily bad, but researchers still don’t understand what it means for how the brain retains information in the long-term.

Image: mashable

When it comes to socializing, Dr. Torous says some research suggests the brain reacts similarly to virtual interactions as it does to real-life exchanges. But, he adds, the rules of online socializing can be “stacked against us” specifically on social media. Feedback that might be subtle or nonexistent in real life now shows up in likes or critical comments. It’s easy to make upward comparisons between ourselves and others.

Whitney Phillips, an assistant professor in the department of communication and rhetorical studies at Syracuse University, says the shift to an online existence has eliminated routine moments of downshifting, in which the brain can transition out of a stressed or overwhelmed state. A bus commute, for example, once offered the opportunity for reflection.

For many people, such chances to process the day’s events and their own emotions are gone, leaving people in a state of “cognitive distress,” says Phillips. Now, they’re pouring themselves into the internet, where Phillips says algorithms are designed to feed them content that keeps them online. In the midst of coping with anxiety or searching for explanations about the pandemic and current events, they may lash out at others. Some, who already distrust authority or conventional expertise, may be drawn into platforms and groups that traffic in conspiracies and misinformation.

“These platforms were not designed for the midst of a mental health crisis,” says Phillips, noting that algorithms haven’t been built with “mental-health guardrails” and don’t account for the ways a platform can exacerbate existing mental health issues. Thus, they can easily fail someone experiencing a mental health crisis.

“People always talk about the biases baked into our technologies and algorithms. But one of the assumptions that doesn’t get mentioned enough is that algorithms are assuming that users are healthy.”

A hybrid life

We’ve known for months that emotional and psychological suffering is widespread. Overdose deaths have increased and more people are seeking help for anxiety and depression.

As a post-pandemic life dangles before us, it’s easy to imagine racing toward it, taking newfound habits that made life bearable for a year and ignoring the wreckage that trails us. We might continue to skip the weekly grocery shopping trip because it means more time spent exercising or playing with children. We might attend religious services in person and virtually because doing the latter reduces social anxiety. A weekly virtual game night with family will stay because it means seeing relatives who live far away more frequently.

Image: Mashable

There are numerous benefits of a hybrid life, particularly when it concerns work-life balance and ensuring access to resources and activities that weren’t previously available to marginalized users. It’s also worth taking stock of what we’re trading away, because it could be some of our humanity.

The internet can’t replace the novelty of real-life human contact and interaction, which is what so many people who’ve lived online for the past year have craved. The downside of an online existence is that it reduces the number of random experiences and encounters that expose us to new, challenging ideas that lead to individual growth, says Dr. Torous.

By exerting even more control over who we do and don’t engage with beyond our screens, we risk weakening our ability to master certain skills and relate with empathy to others. Grocery store visits may be inconvenient, but they’re also lessons in budgeting, decision-making, interacting with strangers, and treating workers well. Attending an exercise class in person can be nerve-wracking, but it’s also an opportunity to embrace a shared vulnerability and practice kindness.

Dr. Torous also believes that it’s just as important to understand how people fared when they couldn’t shift their lives online, either because of access or circumstance. Perhaps they had a harder time getting vaccinated or even accessing accurate information about vaccines, or skipped doctor’s appointments more frequently because they couldn’t be done virtually. Ignoring such outcomes will only create a new kind of health inequity, one in which we fail to comprehend how lacking internet access or the ability to work remotely also affects people’s health and well-being.

Before we arrive at a new normal, we should reckon with the time we’ve spent online during the pandemic and how it’s changed us. What parts of our humanity do we want to hold tight to in a new hybrid life? How did the internet save us and how did it hurt us? How can we minimize distraction, impulsivity, performance, comparison, and unfeeling efficiency in favor of focus, genuine connection, learning, and community?

Until the research can yield better clarity about how the internet affects our well-being, the answers to those questions belong uniquely to those who seek them. Outside of guidance about thoughtful internet use and healthy personal habits, what matters most is who you are and what you do online. If you can’t define those two things, now is the time to start.

If you want to talk to someone or are experiencing suicidal thoughts, Crisis Text Line provides free, confidential support 24/7. Text CRISIS to 741741 to be connected to a crisis counselor. Contact the NAMI HelpLine at 1-800-950-NAMI, Monday through Friday from 10:00 a.m. – 8:00 p.m. ET, or email info@nami.org. Here is a list of international resources.

Additional reporting by Anna Allsop and Jessica Estremera.

The Mashable COVID-19 Anniversary survey was fielded among 1,276 U.S. adults between February 26, 2021 and March 1, 2021. Invitations to the survey were sent to a nationally representative sample of the population (age, gender, region, race/ethnicity) sourced from Alchemer. After data collection, responses were weighted on age to match that of the U.S. Census 2019 American Community Survey. Statistical margins of error do not apply to online-non probability surveys.

For graphic Mixed feelings about time spent online, the answer choice for “I will keep some, if not all, of the online habits and routines” with lowest decimal value between .5% and .99% was rounded down for graphic to total 100%.

For graphic Habits post-pandemic, the answer choice for “Participate in online fitness classes” with highest decimal value between .00% and .49% was rounded up for graphic to total 100%.

For graphic Habits post-pandemic, the answer choice for “Use meditation or wellness apps” with lowest decimal value between .5% and .99% was rounded down for graphic to total 100%.