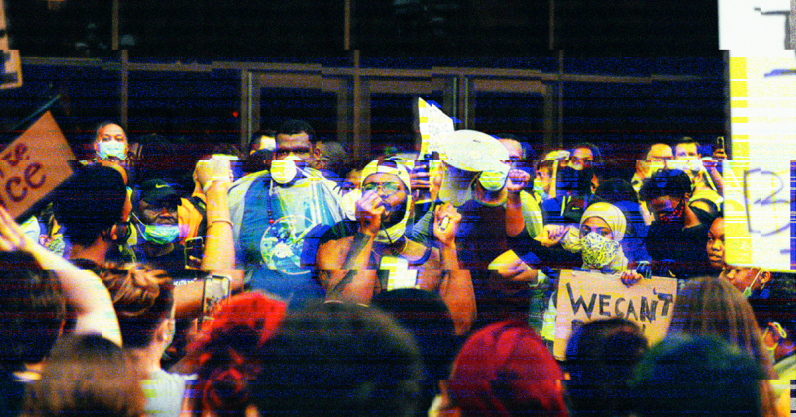

Mass protests have broken out across the United States after a Minneapolis police officer killed black Minnesotan George Floyd while he was in police custody.

One thing demonstrators should be aware of before they head out is that their cellphones may subject them to surveillance tactics by law enforcement. If your cellphone is on and unsecured, not only can your location be tracked, but your messages and the content of your phone may also be retrieved by police either if they take custody of your phone or later by warrant or subpoena.

While some guides recommend buying a separate “burner” phone, or leaving your phone at home entirely, there are tradeoffs and barriers to some of these recommendations. Not everyone can afford to buy a separate phone just for protesting, especially during one of the greatest economic downturns seen since the Great Depression.

And while leaving your phone behind means the data it holds and transmits will be the safest it will ever be, it also means giving up access to important resources. It becomes much more difficult to coordinate with people in other parts of a protest, and to get updates from places like Twitter or others monitoring the action remotely. For many people, their phone is the only camera they own to document what’s happening.

“All protesting and all marches are a series of balancing acts of different priorities and acceptable risks,” said Mason Donahue, a member of Lucy Parsons Labs, a Chicago-based group of technologists and activists that run digital security training classes and have investigated the Chicago Police Department’s use of surveillance technology. “There is a lot of communication ability that goes away if you don’t bring a phone period,” he said.

So if you’re going to take your phone, you might want to do some of the following things to minimize risk.

Subdue your signals (and download Signal)

David Huerta, a digital security trainer at the Freedom of the Press Foundation, said protesters should be prepared for surveillance of their cellphone’s transmissions—even if they don’t make any calls.

In some parts of the United States, law enforcement has tools that can intercept cellphone signals, called “stingrays” or “IMSI catchers.” Stingrays collect the identifying details of phones in the area by “impersonating” cell towers, and newer models are believed to be able to intercept calls and messages, according to TechCrunch.

In 2018, the American Civil Liberties Union identified 75 agencies in 27 states and the District of Columbia that owned stingrays.

Huerta said that since some of these devices can scoop up text messages, you should use an encrypted messaging app like Signal or WhatsApp instead of your default one. (For iPhone users, iMessage is encrypted, but be warned: If you text with an Android phone user, it automatically switches to SMS, which is not.)

Huerta recommends Signal over other apps because it’s battle-tested: In 2016, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia served a subpoena on Open Whisper Systems, the company that makes the app, seeking information about two Signal users for a federal grand jury investigation. The only information the company was holding? The time the users’ accounts were created and the date the users last connected to the app’s servers.

Lockdown location tracking

Law enforcement can also request “cell tower dumps” from telecom providers. In its February 2020 transparency report, AT&T disclosed that it received 1,289 demands for cell tower searches during the second half of 2019. The company said that the demands “ask us to provide all telephone numbers registered on a particular cell tower for a certain period of time.”

Because of the risk of such surveillance, some experts suggest turning off your cellphone altogether at a protest. For instance, the Electronic Frontier Foundation recommends turning your phone off or enabling airplane mode while you’re at the protest, because it ensures that your device won’t be transmitting signals.

But turning off your phone means you won’t be able to communicate with others or use your camera to record. So if you have to keep your phone on, try to at least manage what location information your apps may have. The Verge has a handy guide for Android users, and Business Insider has a comparable one for iPhone users.

You can even turn off all location services entirely:

- iPhone: Settings > Privacy > Toggle ‘Location Services’ off

- Android: Settings > Location > Toggle ‘Use location’ off

Harden your hardware

Another scenario that Huerta suggested that protesters consider is what to do if your phone is seized by law enforcement. If you can, back up your device before heading out to make the decision to wipe it if you find yourself in a tight situation a little bit easier. There are tutorials for both iPhone and Android users.

Encrypting your phone also makes it more difficult to access information if it’s been seized, because files can only be read if someone has the encryption key. DuckDuckGo, the privacy-oriented search engine, has step-by-step instructions for both iPhone and Android users.

Use a passcode, not a fingerprint

Fingerprint and face locks may be convenient ways to secure your phone, but they don’t always work in your favor if your phone is seized by law enforcement.

In the United States, the Fifth Amendment grants people the right not to be “compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against” themselves. While this means you are not obligated to tell someone your passcode, the law is a little murkier on the subject of biometric locks.

In 2014, a Virginia circuit court judge ruled that criminal suspects could be required to unlock their phones with a fingerprint scanner. In 2019, a U.S. District Court judge in California took the opposite stance.

With rulings on both sides of the issue, it’s in your best interest to use a traditional passcode.

And making your passcode as long as possible is a good idea because police have tools that can easily guess simple passcodes.

“Police have these tools by Cellebrite, which essentially try to do tons and tons of guesses really fast on your phone to see what the passcode is. It works pretty effectively for the police because most people use fairly predictable and simple numerical codes,” Huerta explained.

He recommends using an alphanumeric passcode, the longer the better. To add an alphanumeric passcode:

- iPhone: Settings > Face ID & Passcode > Turn Passcode On or Change Passcode > Passcode Options > Custom Alphanumeric Code

- Android: Settings > Security > Screen Lock > Password

To turn your biometric lock off:

- iPhone: Settings > Face ID & Passcode >Tap ‘Reset Face ID’

- Android: Settings > Security & location > Pixel Imprint > Click ‘Delete’ next to each fingerprint

Neutralize notifications

Notifications are normally a great way to quickly check messages, but if your phone is lost or seized, it may reveal information that you’re not comfortable sharing with others.

“Many times, if you don’t have a chance to turn off your phone before a device gets seized, even if law enforcement can’t unlock your phone,” Huerta saids, if your notifications are on, “they don’t even have to unlock your phone, they can just scroll down and see everything that you’re up to.”

Reducing the amount of open information that sits on your locked screen can increase the security of you and the people you’re communicating with.

On Android, you can strip notifications of context by going to Settings > App & notifications > Notifications, going to the “Lock screen” section and turning off Sensitive notifications.

With iPhones, you can change how detailed an app’s notifications are by going Settings > Notifications, selecting that app and then scrolling down to the Options section and setting “Show Previews” to “Never” and “Notification Grouping” to “Automatic.”

You can also turn off notifications entirely:

- iPhone: Settings > Notifications > Set Show Previews to Never

- Android: Settings > Apps & notifications > Notifications > Notifications on lock screen or On lock screen > Don’t show notifications

Think before you share

Photos and videos can reveal more than you intend.

Image files can contain metadata that includes the date the photo was taken, the make and model of the device it was shot on, and even the GPS location of where it was taken. One of the easiest ways to strip a photo of its accompanying metadata is to take a screenshot of it and post that instead of the original image, Huerta explains.

And even if you use a screenshot, check the image for information you might not want to make public, such as indications of location and the identity of other people.

Law enforcement has access to powerful facial recognition databases. Civilians also have tools in reach that can reverse engineer the who, what, and where of your social media posts. One way to mitigate these is to cover up identifying information using an emoji or by drawing over it with a solid color.

Physicalize your phonebook

Phones can run out of battery, get lost, broken, or taken away. Don’t make it your only way to access important contact information.

Reporter Madeleine Davies suggested writing down the phone number of a lawyer or emergency contact on your arm with a Sharpie.

The National Lawyers Guild operates legal support hotlines across the United States that are specifically for people who have been arrested at political demonstrations. Look up a hotline for your area and write it down.

This article was written by Maddy Varner and originally published on The Markup and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.

Corona coverage

Read our daily coverage on how the tech industry is responding to the coronavirus and subscribe to our weekly newsletter Coronavirus in Context.

For tips and tricks on working remotely, check out our Growth Quarters articles here or follow us on Twitter.