Climate 101 is a Mashable series that answers provoking and salient questions about Earth’s warming climate.

The oil giant BP popularized the devious term “carbon footprint” in the aughts to quietly shift blame for the warming planet onto individuals, like you. Yet BP wasn’t the only petrochemical company using clever words to shape the public’s thinking about climate change.

New research shows that, around the same time, ExxonMobil also started employing crafty, calculated PR techniques to steer the onus of global warming away from oil and gas corporations, and onto people living in a fossil fuel-dominated society. (Side note: It’s currently impossible to escape fossil fuels: Even a homeless person today has a big carbon footprint.)

The research, published Thursday in the scientific journal One Earth, found ExxonMobil used advertorials (advertisements format like editorials) in the New York Times as well as other public documents (like company climate reports) to repeatedly promote the narrative that:

-

People’s demand for energy is responsible for the planet’s warming (as opposed to an energy system built on extracting, selling, and burning fossils fuels)

-

Climate change is a future risk (as opposed to an already worsening reality)

By the mid-aughts, the oil giant could no longer perpetually deny or sow doubt about climate change. The evidence for significant human-caused warming, in the form of hundreds of peer-reviewed studies about climate change and global observations, was already clear, even to the company’s own scientists. Instead, ExxonMobil shifted to more subtle messaging to influence how the public viewed climate change. The goal was to underscore that people need fossil fuels, and ExxonMobil fills that demand, the researchers conclude. Accordingly, this promotes the idea that fossil fuel companies are essential, which ultimately helps delay a transition to cleaner energy sources.

“We’ve gone from denialism to delayism.”

“We’ve gone from denialism to delayism,” explained Geoffrey Supran, a research associate in the Department of the History of Science at Harvard University and one of the study’s authors. Supran and his coauthor, Harvard science historian Naomi Oreskes, used computer programs to scan text in over 200 documents published between 1972 and 2019 (advertorials, published scientific papers, company documents, et cetera) to identify how often certain terms appear, and where they appear.

Take the word “risk.” Prior to the merger of Exxon and Mobil in 1999, the companies used the term “risk” to explain or describe climate change (as in the “risk of climate change”) once. But after 2000, the study found the oil giant used “risk” 46 times, employing it an average of one time in each advertorial.

The word “risk” creates a subtle, but powerful narrative.

“A risk is something that may or may not happen,” said Supran. “But climate science had already demonstrated that climate change was underway and causing damage. It’s incredibly insidious.”

“It’s incredibly insidious.”

Indeed, decades earlier ExxonMobil’s own climate scientists predicted (accurately) that burning fossil fuels would drive up CO2 levels in the atmosphere and stoke significant planetary warming.

This @exxonmobile chart from 1982 predicted that in 2019 our atmospheric CO2 level would reach about 415 parts per million, raising the global temperature roughly 0.9 degrees C.

Update: The world crossed the 415 ppm threshold this week and broke 0.9 degrees C in 2017 1/ pic.twitter.com/sLpOVkwzTF

— Tom Randall (@tsrandall) May 14, 2019

Blaming consumers

Beyond emphasizing that climate change is only a risk, the study identified how ExxonMobil sought to pin climate change on individuals. Again, the fossil fuel giant subtly employed specific words; they certainly already understood the power of tactful phrases. The researchers note that Herb Schmertz, Mobil’s vice president of public affairs between 1969 and 1988, had written: “Grab the good words — and the good concepts — for yourself.” He also added: “[B]e sensitive to semantic infiltration, the process whereby language does the dirty work of politics … Be sensitive to these word choices, and be competitive in how you use them.”

To emphasize individual responsibility for climate change — similar to how BP successfully infused the phrase “carbon footprint” into our everyday lexicon — ExxonMobil underscored consumers were demanding energy. Consumers, of course, didn’t have much of a choice: We were all born into a world largely powered by burning fossil fuels. (Though that’s now starting to change.)

“Language does the dirty work of politics”

The study cites poignant examples. In 2008, an ExxonMobil advertorial said: “By 2030, global energy demand will be about 30 percent higher than it is today … oil and natural gas will be called upon to meet … the world’s energy requirements.” Meanwhile, a 2007 advertorial recommended that consumers solve the problem of fossil fuel demand. The company offered “steps to consider,” including “be smart about electricity use,” “heat and cool your home efficiently, improve your gas mileage,” and “check your home’s greenhouse gas emissions” using an online calculator. (This would assume, somewhat presumptuously, people aren’t already attempting to avoid paying higher monthly utilities for unnecessary energy waste).

Yet calculating how much energy your TV or blender potentially uses, or deciding not to take a much-needed family vacation, won’t stop planetary warming. The worst pandemic in a century is vivid proof: CO2 levels in the atmosphere continued to rise even as individuals’ “carbon footprint” shrank considerably during societal lockdowns, largely from lack of travel. But for ExxonMobil, the point is to frame fossil fuel companies as essential, to fulfill consumer needs and demand. Ultimately, this delays climate action.

“Blaming consumers for driving climate change has been a highly effective strategy.”

“Blaming consumers for driving climate change has been a highly effective strategy by fossil fuel companies,” said John Cook, a researcher at the Climate Change Communication Research Hub at Monash University in Australia who had no role in the new study. “In public and policy discussions about climate solutions, it shifts the focus from transitioning away from fossil fuels, and instead emphasizes how individuals should reduce their personal carbon footprints.”

This won’t achieve much, as far as global temperatures are concerned. “Improving individual efficiency can only achieve a tiny fraction of the emissions reductions required to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, so the strategy has been a convincing red herring,” Cook added.

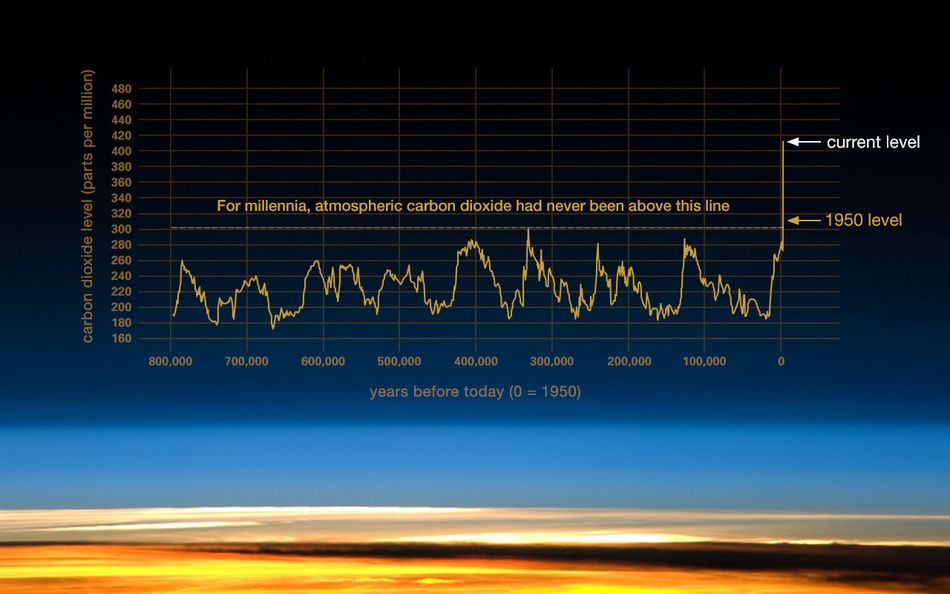

Atmospheric CO2 levels have skyrocketed to their highest levels in at least 800,000 years.

Image: nasa

In sharp contrast to ExxonMobil’s public advertisements, the company’s internal and academic publications described human-caused climate change as a “problem caused by fossil fuel supply and burning.” In 1978, Exxon scientist James Black told the Exxon Corporation Management Committee that “[F]ossil fuel combustion is the only readily identifiable source [of CO2 consistent with the rate and scale of] observed increases …” Other documents noted the CO2 increase in the atmosphere is “due to fossil fuel burning” and “fossil fuel combustion.”

The careful ways ExxonMobil chose to publicly promote its ideas about climate change, versus what its own scientists and executives discussed in private, are intentionally subtle. But with the help of computer algorithms, patterns are revealed, and so are ExonnMobil’s efforts to frame the climate change narrative. “There are treasure troves of information if you can spot the patterns,” said Supran.

“The most effective propaganda is that which relies on framing rather than on falsehood.”

ExxonMobil’s clever efforts are a form of propaganda, just like BP popularizing the term “carbon footprint.” The goal isn’t to try and spread outright lies or ideas people can easily refute, like “climate change isn’t happening” when ice sheets are clearly melting and the planet is growing warmer. The researchers quote the political scientist Michael Parenti: “The most effective propaganda is that which relies on framing rather than on falsehood.”

In a statement sent to Mashable, Casey Norton, a corporate media relations manager at ExxonMobil, said: “This research is clearly part of a litigation strategy against ExxonMobil and other energy companies.” A plethora of state and local governments along with private individuals are indeed suing fossil fuel companies for knowingly polluting and warming the planet, and such peer-reviewed research could potentially one day be part of an argument showing fossil fuel corporation liability for climate change, though that’s unknown. Norton added that “ExxonMobil supports the Paris climate agreement,” which is a global pact to limit the worst consequences of climate change by keeping warming under 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels. (With continued fossil fuel burning, this goal may be out of reach.)

Today, ExxonMobil — which earned $2.7 billion during the first quarter 2021 — continues to promote ideas about “risk” and “energy demand.”

-

On its climate and emissions webpage (as of May 12, 2021), the company writes [emphasis added]: “With a longstanding commitment to investments in technology and the ingenuity of our people, ExxonMobil is well positioned to continue to provide the energy that is essential to improving lives around the world, while managing the risks of climate change.”

-

The company recently tweeted a quote from CEO Darren Woods, extolling the importance of gas in powering growing and developing economies: “As that economy grows, as peoples’ lives get better, you’re going to see an increased consumption of energy and obviously gas is going to play a key role in that.”

It’s subtle framing. And that’s the point.

“Over the last two decades of climate misinformation, we’ve seen a transition from science denial to solutions misinformation and more subtle framing such as blaming individual consumers,” said Cook. “This underscores the need for raising people’s awareness of these kinds of rhetorical tricks in order to inoculate the public against the more subtle forms of misinformation.”

WATCH: Even the ‘optimistic’ climate change forecast is catastrophic