It was a cold night in November 2016 when I first saw the sign.

Long runs in the winter darkness were my response to post-election anxiety. Music both angry (DJ Shadow’s Nobody Speak) and somber (Leonard Cohen’s You Want It Darker) provided the soundtrack as I chewed over the president-elect’s racist, sexist, anti-immigrant, fact-denying rhetoric. So many groups of people would be vulnerable in the next four years. In the coming battles to protect them, where did we start? And how could we tell who was on our side?

As if by magic, the answer appeared in a well-lit yard: A 26-word statement rendered in colorful letters on a black background. “In this house we believe,” it began, followed by this concise summary of allyship: “Black Lives Matter. Women’s rights are human rights. No human is illegal. Science is real. Love is love. Kindness is everything.”

I had what has since emerged as the two most common reactions to the sign: A fist-pumping “fuck yeah” and “oh, I gotta take a picture of that.”

Little did I know that the sign had originated thousands of miles away, earlier that month, as a collaborative effort by a group of Wisconsin women whose story I tell below. Nor did I suspect how viral it would go, that it would be placed in yards around the world, or that it would have such longevity. It was seen widely at the Women’s March of January 2017 and at the anti-police brutality rallies of June 2020.

“No matter what the protest is, you can yank this out of your lawn and you’re good to go,” says Jennifer Rosen Heinz, one of those Wisconsin women.

At the same time, this remarkably consistent message appears to be fraying at the edges. At time of writing, the top-selling yard sign on Amazon is an unauthorized version that omits “in this house,” the plant-your-stake intro that made the original so powerful, and replaces the second line with “feminism is for everyone,” which has been criticized by feminists on Reddit despite somewhat referring to the title of a book by social activist bell hooks. And in these days of widespread rage at systemic racism, masked for too long by polite white silence, not even the sign’s creator is sure “kindness is everything” is still the right message.

Still, the sign stands as one of the more enduring legacies of Trump-era resistance. As a political credo, it is more bold and memorable than anything the Democratic party has come up with in the last four years. Whether its central message survives, or collapses into a thousand more personal versions, the sign has already done a great deal of good.

Don’t take it from me; take it from this gay couple who decided to buy their house because someone in the neighborhood had put it out front. The sign may be just a place to start in terms of activism, but it isn’t performative wokeness. It can make a genuine difference in people’s lives.

‘I needed to remember to do the research’

Kristin Garvey is hardly what you’d call a political activist. She’s a soft-spoken youth services librarian in Madison, Wisconsin, and a mom of two. When the story of the sign is told, she shies away from taking credit. “I’ve never been real comfortable,” she says, “because I don’t feel like I did much.”

Which is a fair point; after all, none of the sign’s statements originated with Garvey. Black Lives Matter began as a hashtag in 2013, courtesy of Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi. “Women’s rights are human rights,” made famous by Hillary Clinton in a speech in Beijing in 1995, dates back to at least the 1980s. “No human is illegal” has been a rallying cry of immigration activists since 2015, when they persuaded Clinton to stop using the “i” word. “Love is love” is an LGBTQ group that originated in Alaska in 2012 and part of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s 2016 Tony acceptance speech. Science is real is a 2009 They Might Be Giants song, and a phrase millions of us have shouted at Fox News-watching relatives for years.

Garvey was the first to put them all together, but more notable was when she did it: Wednesday November 9, 2016, the day after Trump’s election. Like many of us, she spent that morning in a hazy, sleepless state of shock. Unlike many of us, Garvey lived in one of three states where Donald Trump eked out his razor-thin electoral college win. By their votes — or more likely, by their lack of votes — many of her neighbors had tipped the scales towards a hate-fueled and proudly ignorant president.

So while the kids napped at home with her husband, she texted him that she was going to the store for a piece of white foam board and some Sharpies. The sign was in her yard that afternoon.

Pay attention, political strategists: Garvey spent zero time agonizing over messaging. If she had, surely she’d have eased her neighbors in with the relatively anodyne “kindness is everything” rather than Black Lives Matter — a movement which, according to multiple polls, wasn’t supported by a broad majority of Americans until 2020.

But this was a personal to-do list as much as a statement of solidarity. Garvey knew there were more steps to be taken than simply putting out a sign. “I’m not someone who can speak out eloquently,” she says. “I just put the sign in my yard for myself, to remember that I need to do the research, and to remind my kids.” The first point of research, the one she admits she knew the least about, was Black Lives Matter. That’s why it went first.

Garvey was as good as her to-do list. For the fiction section of the library, she purchased more books with more diverse characters; for the nonfiction section, more tomes on Black history and activism. She took an 8-week online course on Black history called Justified Anger — which is why she says that if she was writing the sign now, she would probably add “anger is justified” at the bottom.

That Sharpie-drawn sign is now in the National Women’s Party Museum, devoted to the century-old National Woman’s Party, a political organization in Washington, D.C. Garvey doesn’t need it; she sees the professional renderings everywhere. Her sister, who lives in New Zealand, recently texted to say she’d seen it in the wild there. “People ask if I’m mad about the different versions,” Garvey says. Her response: “I just don’t want people to make a profit from it.”

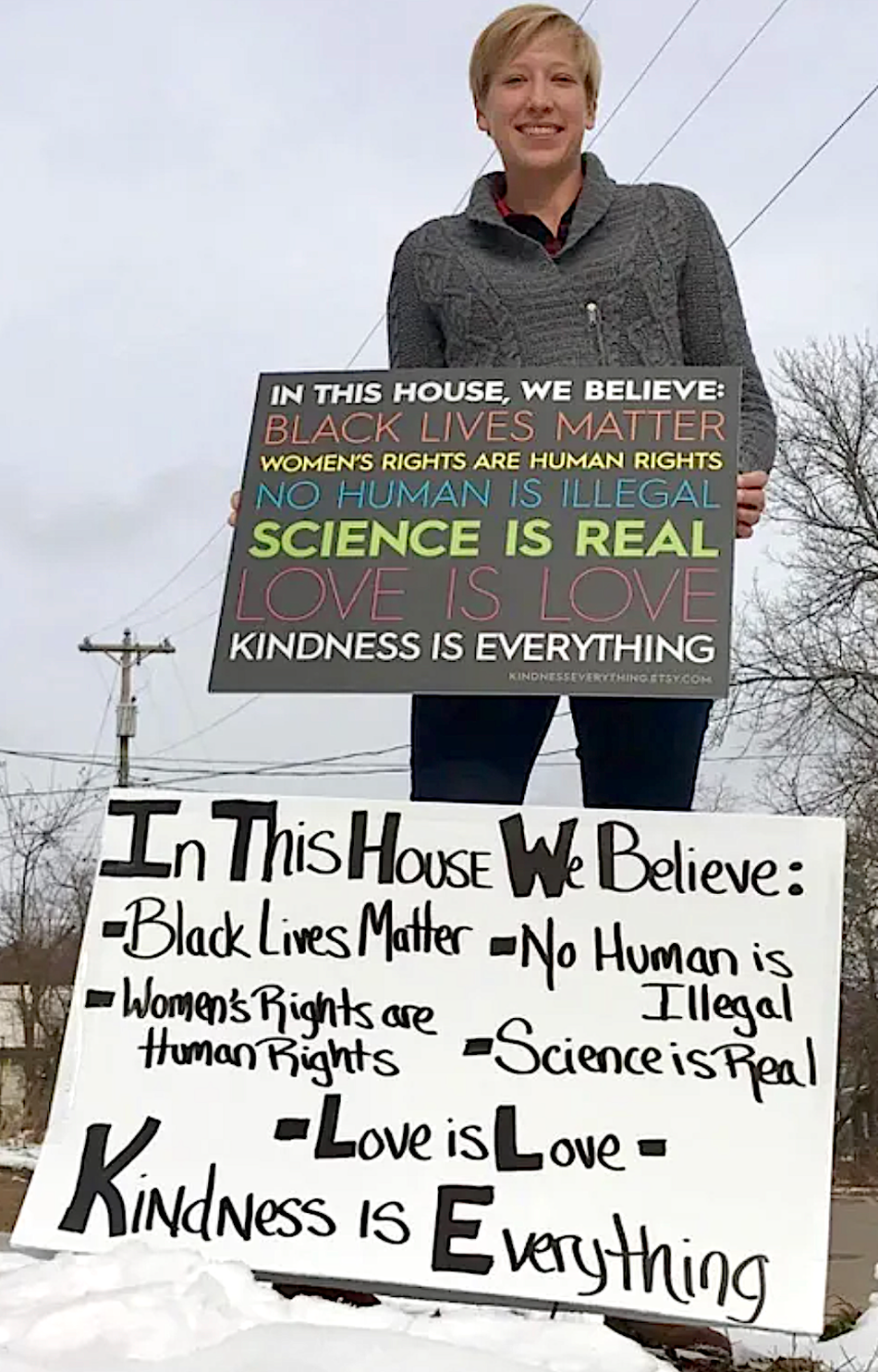

Kristin Garvey with her original sign, now in the National Women’s Party Museum in Washington D.C., and the redesign.

Image: jennifer rosen heinz

‘I’ve wondered if it could make me a target’

Within a matter of hours of the sign’s placement, a remarkable chain of events was underway. A woman who happened to walk by Garvey’s house had taken a picture of it and posted it to a friend’s Facebook wall. “You should make signs like this,” commented the friend, tagging another friend. That friend, Jennifer Rosen Heinz, agreed enthusiastically. Unlike Garvey, Rosen Heinz is most definitely an activist. “I’m kind of the carnival barker,” she laughs. And she felt the profound need for something that the anti-Trump resistance could rally around.

It’s hard to recall now, but in those early months we rallied around a variety of symbols that didn’t pan out. Remember when we were supposed to wear safety pins? As it turned out, that symbol was not only too small, it was too ambiguous. What kind of safety were you offering? To whom, exactly, were you an ally? The Rebel Alliance/Resistance logo was popular for a while, but you could just as easily be wearing that as a Star Wars fan.

“Lots of people think they support these values, but too often there’s an asterisk,” Rosen Heinz says. “Like ‘oh, it’s okay to be gay if you don’t mention it.’ We needed a statement.”

Having found one that just seemed to click with a wide swath of people, Rosen Heinz roped in a local artist, Kristin Joiner, who turned the sign we see today around in 24 hours. The black background was to help it stand out in the Wisconsin snow; it just so happened to make the rainbow-colored lines more arresting. The pair tracked down Kristin Garvey before getting their blessing to put it online. They made signs for local pickup, and offered it for download online, in return for a $5-per-sign donation to the ACLU.

By November 13, another friend had posted the sign to Pantsuit Nation, a popular Facebook group for Clinton supporters, where it blew up. A friend of Rosen Heinz’s used it as their Facebook cover image, and for some reason that photo got 30,000 shares. From the start, the sign was more popular in some locations than others. Some $40,000 of donations came in just from Austin, Texas in those early months. South Orange, New Jersey was another.

Rosen Heinz was besieged with requests. The Unitarian Universalist Church wanted to use it. People wanted versions that began “in this school” or “in this apartment.” The “in this house we believe” meme — which uses ASCII art and a variety of humorous slogans — also appears to date to mid-November 2016. Though no one is quite sure whether it has any connection to what was now known as the Kindness Is Everything sign, it’s quite a coincidence.

Garvey, Joiner, and Rosen Heinz didn’t have the time to manage the phenomenon; they all had day jobs. (Rosen Heinz did business development for a local magazine.) So they made the decision to hand over ownership of the sign to the Wisconsin Alliance for Women’s Health, a tiny advocacy group funded to this day by proceeds from the sign. “It’s like giving someone a little 401K,” Rosen Heinz says.

Rosen Heinz still proudly displays the sign outside her home. “I’ve wondered if it could make me a target,” she says. After all, not everyone agrees with these statements. People have told her they’ve had their tires slashed in the driveway outside houses bearing the sign, and that homeowner associations have fought over whether it should be allowed. A friend of Rosen Heinz in Texas had a running battle with a neighbor who kept taking it down, saying it violated the HOA rules on political signage. But the HOA rules had nothing to say about flags. “So she got the biggest-ass flag you can find” with the message on it, Rosen Heinz says. The HOA had no rule against flags.

The risk of controversy is part of the reason the sign has staying power. It says a lot of things that aren’t said often enough in enough neighborhoods around America, and it always grabs the eye. A more telling story, as far as Rosen Heinz is concerned, is that of an African immigrant UPS driver who saw the sign, wept, and asked if he could take a selfie with it.

That kind of personal meaning makes up for a lot of uncertainty about the content. Rosen Heinz too has gone back and forth on whether “kindness is everything” is too anodyne for the Trump years, but has come to accept it as part of the sign’s poetic flow. She too has fielded requests for new lines, and has no problem with people adding their own: “But then the question is, how long is your sign?” More egregious in her mind: Versions of the sign rendered in Papyrus or Comic Sans. “I’ve tried to desensitize myself to all that,” Rosen Heinz says. “You could drive yourself crazy.”

‘This is the heart of the progressive movement’

Sara Finger, head of the Wisconsin Alliance for Women’s Health, was overjoyed to become the custodian of the sign and its message. The words aren’t trademarked, but Joiner’s design is. On Cafe Press and Zazzle, the group’s official store offers all the merch you might expect — including the latest bestseller for the COVID-19 age, face masks.

“We’ve generated at least $130,000 in revenue” from its message, Finger estimates. Which is a big deal for a tiny organization where Finger manages payroll, social media, and lobbying. “Kindness is Everything funds are everything for us,” she says.

Unfortunately, there are many more versions being sold that don’t benefit Finger’s organization. This one on Look Human, for example, is unauthorized. As is the bestselling sign on Amazon, which is sold by a tiny Portland company called Signs of Justice — but given the company’s own inspiring story (it was founded by an interracial couple who were also terrified by the effects of Trump’s election), Finger elected not to take action. Only once has she called in a lawyer, who worked pro bono for a couple of months to help get an Etsy seller to stop profiting from an exact replica.

Which is not to say that Finger is happy to let every other instance of its appearance go. When Oprah was going door to door with Stacey Abrams, the Democratic gubernatorial candidate in Georgia in 2018, the pair came across the sign and had their picture taken with it. “We said ‘oh, gosh darn it, we could have gotten some credit,'” says Finger.

Regardless of lost revenue, Finger is proud and pleased that the words on the sign have become what she calls “the heart of the progressive movement” — a litmus test, in effect, for the entire political left.

“This is what it’s come down to,” she says. “One party has this in their hearts, and the other…has it in their hearts and won’t say?” Finger shrugs. “I have hope because all these sentiments are natural to who my kids are. In 30 years, I hope they won’t be controversial.”