China’s “zero-COVID” policy put the Beijing Winter Olympics under some of the strictest coronavirus protocols in the world.

The Games took place in a “closed-loop” environment comprised of gated “bubble areas” that contained housing, event locations, and transport links.

There were also no tickets sold to the general public, while many media professionals worked from home due to COVID concerns.

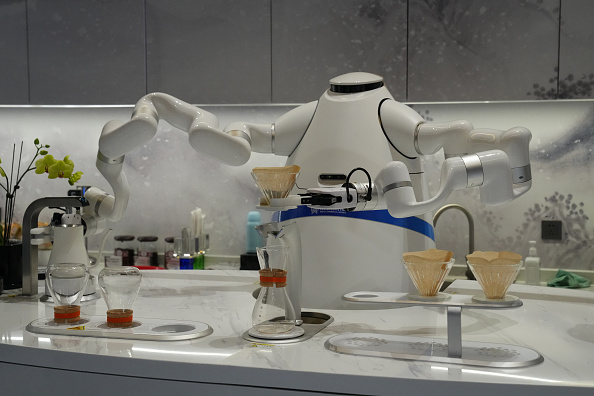

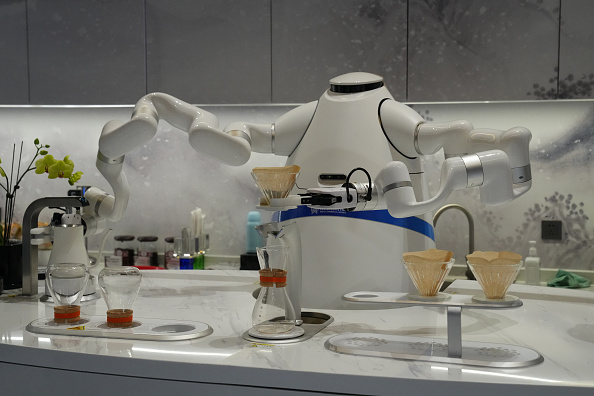

The conditions left Getty Images, the official photo agency for the International Olympic Committee, with reduced support teams on the ground. To tackle the challenges, the team tapped into robotic cameras and remote editing.

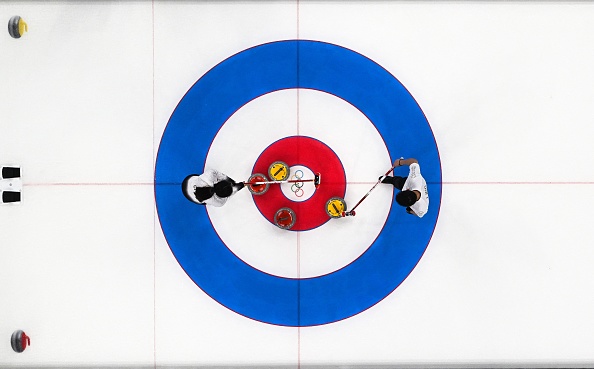

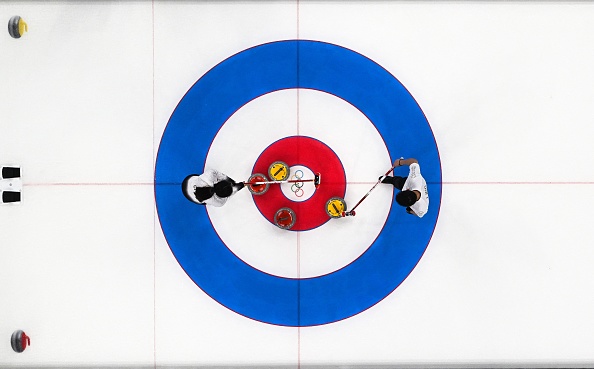

Getty mounted cameras in robotic rigs that are controlled remotely. This enabled the agency to capture images from angles that a human photographer can’t access, such as inside ice hockey nets or underneath ski jumps.

“It’s all controlled via software and a joystick – kind of like playing a video game,” Michael Heiman, Getty Images’ Global Head of Editorial Operations, told TNW.

robots worked alongside people on the ground.

robots worked alongside people on the ground.

In a Switzerland vs. Finland ice hockey match, for instance, there were two human photographers, and remote cameras above the Olympics logo, overlooking the goal, and inside the net.

Getty has used remote cameras since the 2012 London Olympics, but Heiman said the early systems were slow and clunky:

The speed at which the cameras operate and the preciseness with which you can control them has gotten a lot better. When we did this in 2012 the cameras had Ethernet ports on them, but they didn’t have any kind of intelligence built-in. It was like taking an expensive robotic rig and putting a very expensive camera on it and the two weren’t really meant for each other.

Another new technology for Beijing 2022 was remote live-editing. Getty’s software transferred photos via FTP over a virtual LAN and onto remote editors around the world.

The total process of sending images from cameras to customers and websites took around 30 seconds.

One technology that could play a bigger role in future Olympic Games is AI.

Heiman isn’t 100% comfortable with the tech’s accuracy yet, but expects it to become a useful tool for identifying people in an image.

Facial recognition could expedite captioning at some events, while number recognition could be used on athletes whose faces are obscured, such as ice hockey players.

The techniques still require human validation for now, but they could prove useful long after the pandemic ends.