Mashable’s series Algorithms explores the mysterious lines of code that increasingly control our lives — and our futures.

TikTok’s algorithm is almost too good at suggesting relatable content — to the point of being detrimental for some users’ mental health.

It’s nearly impossible to avoid triggering content on TikTok, and because of the nature of the app’s never-ending For You Page, users can easily end up trapped scrolling through suggested content curated for their specific triggers.

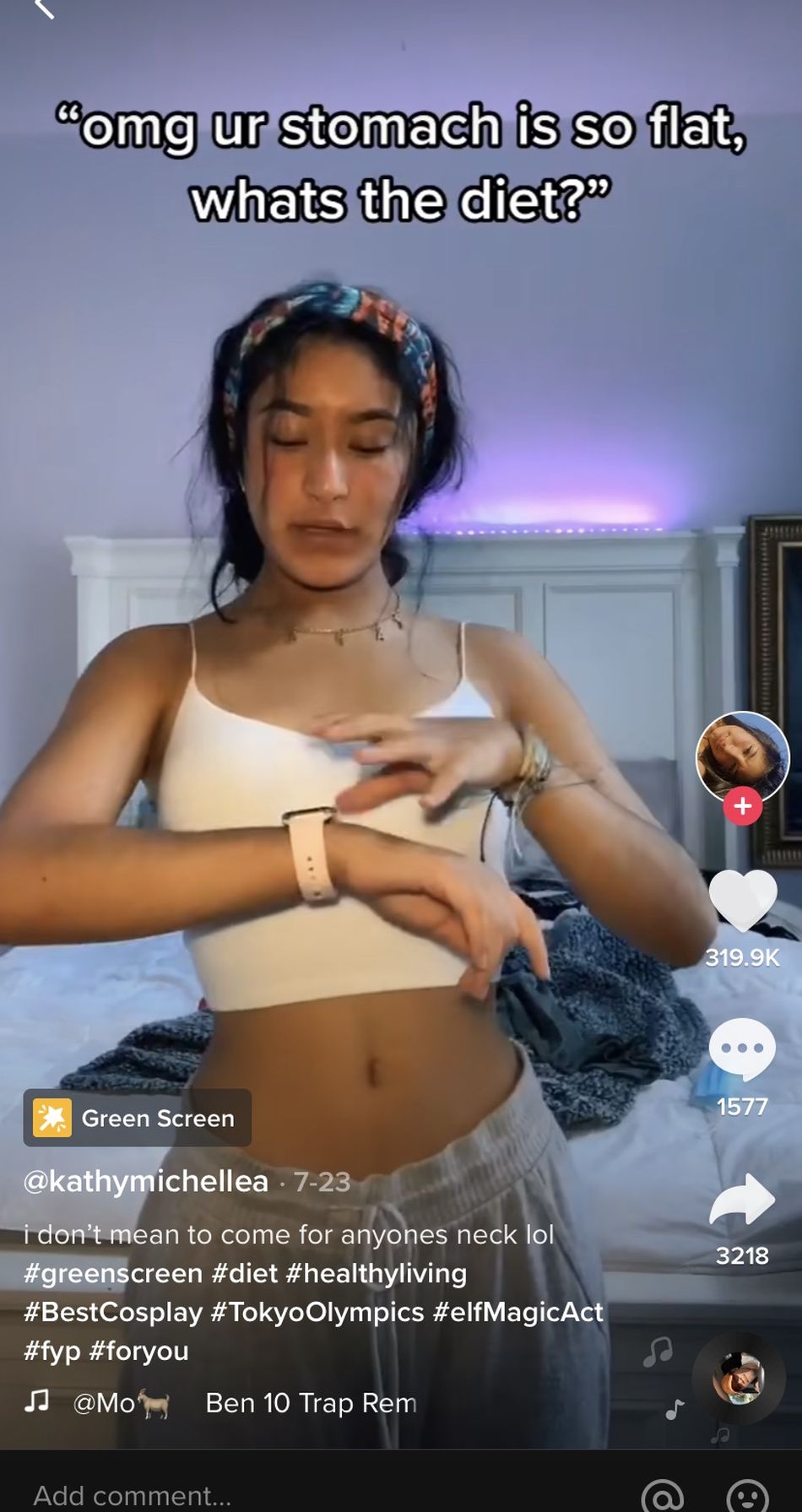

Videos glorifying disordered eating, for example, are thriving on TikTok. The tag #flatstomach has 44.2 million views. The tags #proana and #thinsp0, short for pro-anorexia and thin inspiration, have 2.1 million views and 446,000 views, respectively. As senior editor Rachel Charlene Lewis wrote in Bitch, pro-ana culture and the internet intertwined long before TikTok’s ubiquity on teenagers’ phones. During the early days of social media, young people used forums and message boards to track their weight loss and swap diet tips. In the early 2010s, eating disorder blogs glorifying sharp collarbones and waifish ribcages flourished on Tumblr. Most recently, the community of eating disorder-themed Twitter accounts used memes to encourage members to stick with their restrictive meal regimens.

While it was possible to stumble across fragments of the ED (eating disorder) community on other platforms, users were more likely to find it by intentionally seeking out that community. But on TikTok, users are algorithmically fed content based on their interests. If a user lingers on a video tagged #diet or #covid15, a phrase used to refer to weight gained in quarantine with 2.1 million views, the app will continue to suggest content about weight loss and dieting. It’s a slippery slope into queuing up food diaries about subsisting on green tea, rice cakes, and other low-calorie foods popular in the disordered eating community.

“Rather than flood the user with content they may or may not enjoy, each online platform uses algorithms to better control the ‘flow’ of water through the hose.”

David Polgar, a tech ethicist who sits on TikTok’s Content Advisory Council, likens TikTok’s For You Page to a hose connected to a large water source. Rather than flood the user with content they may or may not enjoy, TikTok uses an algorithm to better control the “flow” of water through the hose.

“It brings up very delicate questions around making sure that it’s not reinforcing some type of echo chamber filter bubble, so that it doesn’t lead anybody down rabbit holes,” Polgar said in a phone call. YouTube, he noted, received significant backlash last year for suggesting increasingly radical right-wing conspiracy videos based on users’ watch history.

My descent into ED TikTok began, ironically, with videos criticizing a popular creator for being insensitive to eating disorder recovery. Addison Rae Easterling, a 19-year-old TikTok dancer with 56 million followers, caught flak in June for promoting her sponsorship with American Eagle by dancing to a song about body dysmorphia. Dressed in a pair of light-wash mom jeans, Easterling dances to the chorus of Beach Bunny’s “Prom Queen.” The song does include the phrase “mom jeans,” but it’s preceded by the lyrics, “Shut up, count your calories. I never looked good in mom jeans.”

Easterling faced backlash from other TikTok users, especially those in ED recovery. In one duet with the now-deleted video, a young woman drags her feeding tube into the frame and scoffs at Easterling’s dance. Other users captioned videos with their own experiences with eating disorders in an effort to point out how severe they can be. One tried to point out how insensitive Easterling’s sponcon was by describing her own restrictive eating habits. Another TikTok user tried to emphasize how destructive eating disorders can be by graphically recounting how she used to fantasize about slicing off her stomach.

TikTok users unintentionally fed into the very mentality that drives eating disorders to flourish: competition.

In an effort to criticize Easterling, TikTok users unintentionally fed into the very mentality that drives eating disorders to flourish: competition. Ashley Lytwyn, a registered dietitian nutritionist who specializes in treating patients with eating disorders, told Mashable that even in recovery, comparing symptoms can be competitive. Many who suffer from eating disorders don’t just strive to be thin, but to be the thinnest. Those in recovery may even want to be the sickest.

“Individuals with eating disorders at times don’t feel like they are ‘that bad’ if they aren’t the sickest in the room, or on social media,” Lytwyn said in an email. “This can be extremely dangerous as individuals with ED will go to great lengths to ‘win’ at being the sickest and often put their bodies in extreme harm to get there.”

Calling out Easterling by highlighting extreme habits like chewing ice and purging after a food binge is actually more harmful for ED recovery than Easterling’s original dance was, as it can motivate someone to mimic that behavior and relapse. As I engaged with well-meaning but misguided content describing calorie counting, extreme exercise, and other self-destructive habits, my For You Page began showing me more content about fitness and diet. Only a few days after liking a video tagged #edrecovery, my For You Page showed me a video of a woman achieving her flat stomach by skipping meals in favor of chewing gum and drinking tea.

It isn’t just ED content that manages to land on TikTok users’ For You Page. Videos about self harm, suicide, sexual assault, abuse, mental health issues, and a slew of other potentially triggering topics circulate on the app. Just as on any other form of social media platform, it’s impossible to totally shield yourself from coming across triggering content. TikTok, however, is uniquely structured to continue showing triggering content if users engage with it.

TikTok, however, is uniquely structured to continue showing triggering content if users engage with it.

In an effort to be more transparent amid security concerns because of the company’s Chinese ownership, TikTok revealed how its algorithm works a few months ago. When a user uploads a video, the algorithm shows it to a small group of other users who are likely to engage with it, regardless of whether or not they follow the user who posted the video. If the group engages with it, either by liking it, sharing it, or even just watching it in its entirety, the algorithm shows the video to a larger group. If they respond favorably, the video is shown to a larger group again, and this process continues until the video goes viral.

To determine an individual user’s interests, TikTok uses a variety of indicators such as captions, sounds, and hashtags. If a user has engaged with those indicators, like watching a video captioned with a certain phrase all the way through to the end, the algorithm takes it as a green light to continue recommending videos like it.

It’s less of a malicious Black Mirror-like plan to herald the robot takeover and more of an unfortunate oversight in a well-meaning feature. The concept of banning potentially triggering content altogether has sparked debate over whether private companies, like social media platforms, have an obligation to uphold free speech principles. It’s also incredibly difficult to moderate this kind of content. TikTok users manage to bypass TikTok’s content flags by misspelling certain phrases. Suicide, for example, becomes “suic1de” or in more morbidly lighthearted videos, “aliven’t.” The tag #thinspo is blocked, but the tag #thinsp0 isn’t. Users won’t be able to find any content tagged #depression, but #depresion has 498.8 million views.

Some social media users — whether on TikTok, Twitter, or YouTube — agree to an unofficial social contract to use trigger warnings when discussing potentially traumatic content. Trigger warnings are especially controversial in the classroom and conservative critics associate the term with college students who can’t handle difficult conversations. While trigger warnings were originally designed to allow survivors with PTSD to avoid traumatic content, their efficacy is questionable. In an informal experiment, TikTok user loveaims prefaced photos of herself at her lowest weight while struggling with anorexia with two trigger warnings. Then, instead of showing any photos, she called out other TikTok users.

“This proves trigger warnings do nothing,” loveaims wrote in her video. “People will ignore them. They do not ‘warn others’ from the very triggering and not okay content people post.”

So what can you do to avoid getting sucked into scrolling yourself into a potential relapse? We can’t expect creators to avoid triggering content entirely, and we can’t expect everyone to have the same standards for what “counts” as potentially harmful content.

It’s also difficult to proactively avoid triggers on TikTok — although users can indicate that they’re not interested in certain videos and can block certain sounds and specific users, they can’t block keywords. As a member of TikTok’s Content Advisory Board, Polgar wants to see more customization available so users can better control what content they see.

“If something is offensive to a person and they’ve indicated that, there should be a better ability to lessen the likelihood that that content is shown again, because that should be their decision,” Polgar said.

Furthermore, platforms can do a better job of partnering with mental health organizations to provide resources related to certain flagged phrases. In response to rampant misinformation about COVID-19, for example, TikTok added a banner to videos tagged with certain keywords that led users to information about how the virus spreads and how to prevent contracting it. Polgar said the platform is in the process of working with mental health organizations to provide mental health resources to its users.

“What a lot of platforms are trying to do is basically…ensure that one, if it’s offensive or triggering to you, that you have an easy way to alter seeing it that frankly is in better, more intuitive design,” Polgar continued. If users come across something potentially triggering, they should be able to “click something” that will protect them.

On the other end, users can avoid content that may harm their mental health by not engaging with it. That’s much easier said than done, however, and given how difficult relapse can be to avoid, Lytwyn suggests a more extreme measure. If you find yourself stuck in a spiral of algorithmically generated trauma, delete your account and start fresh.

“This reset[s] the algorithm so that food accounts, disordered eating accounts, or bikini accounts aren’t constantly flashing on your feed,” Lytwyn wrote. She added that a recent patient started a new TikTok account and intentionally sought out videos about interior design and architecture. By watching, sharing, and commenting on videos with specific tags, Lytwyn’s patient curated an aesthetically pleasing feed of non-ED content. “We can’t completely get rid of ever seeing an account like that, but if the majority of the feed is a completely different industry, then it is less likely to be influential when it comes up.”

If you’ve already built up a large following and don’t want to have to start from scratch, you can also shape your For You Page to show you other content instead of videos about eating habits. By intentionally engaging with videos that aren’t centered on food and dieting, TikTok users can train the algorithm to show other content instead.

Granted, a possible trigger may make its way through your curated feed every now and then. In those cases, Lytwyn said, it’s best to turn off your phone, call your support person, whether a therapist or a loved one, and ask for a distraction.

If you find yourself trapped in a web of content that makes you uncomfortable, start following tags that bring you joy — elaborate Animal Crossing island designs, soothing knitting videos, newborn kittens taking their first steps may be good starting off points. Just because you might come across triggering videos on TikTok doesn’t mean they have to make up your entire For You Page.

If you feel like talking to someone about your eating behavior, call the National Eating Disorder Association’s helpline at 800-931-2237. You can also text “NEDA” to 741-741 to be connected with a trained volunteer at the Crisis Text Line or visit the nonprofit’s website for more information.