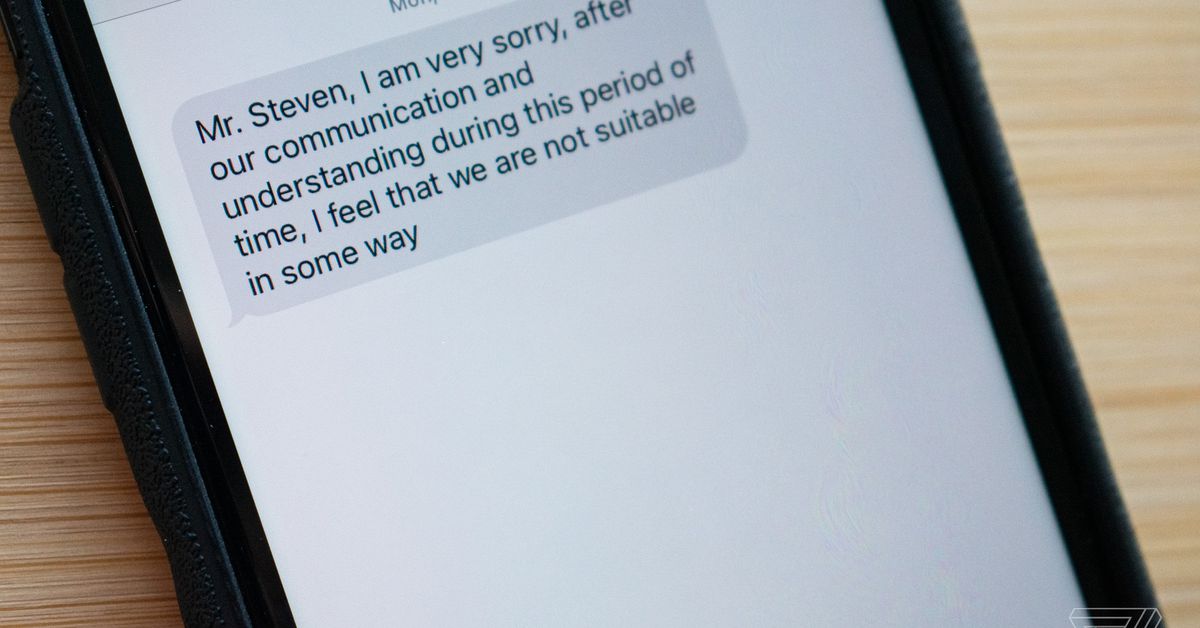

The text that arrived at 3:51PM on Monday, March 28th, seemed innocent at first.

“Mr. Steven,” it read, “I am very sorry, after our communication and understanding during this period of time, I feel that we are not suitable in some ways.”

That’s odd, I thought, must be a wrong number. But who was this mysterious Mr. Steven? What was the nature of the disagreement? What the heck did Mr. Steven do to offend this person? I was intrigued — but not enough to respond.

Several weeks later, I received another text, this time from someone named “Amy” asking about “a location for coffee.” A couple days after that, “Irene from Vietnam” reached out to ask if I was still living in New York. And then “Sophia” texted, calling me “Laura” and asking about a party we both attended over the weekend.

And then “Sophia” texted, calling me “Laura” and asking about a party we both attended over the weekend

These “wrong number” texts are clearly the work of some fraudster, but honestly I don’t really mind. To me, they’re more sublime than annoying, hinting at a possible missed connection or mistaken identity. The fact that they’re not openly soliciting me for money or just outright phishing me helps take some of the sting out of it. They’re certainly more tolerable than the torrent of emails I’ve received from feckless Democratic politicians begging for more money in the wake of Roe v. Wade being overturned.

I’m 100 percent sure this wrong-number text is some sort of scam, but I appreciate that criminals have finally moved on from selling car warranties to whatever this is pic.twitter.com/ltSoJmpwGz

— Casey Newton (@CaseyNewton) May 2, 2022

Max Read wrote about this phenomenon of “wrong number” text spam in his most recent Substack, calling it “a rich world, animated by detail and alive with mystery,” and I tend to agree. Spam is more pervasive than ever — a recent study found that Americans receive an average of 3.7 scam calls and 1.5 scam texts per day — and practically all of it is banal and forgettable.

This new genre of spam isn’t. And that’s probably what makes it more pernicious, but I can’t seem to get too worked up about it.

Read does a deep dive — I encourage you to read his essay — into what are likely “romance scams,” also known in China as “pig butchering” scams. They play on the recipients’ loneliness, sympathy, or general cluelessness to lure them into some sort of fraud that typically results in them being scammed out of a bunch of money. We all love a good scam story, but honestly, these types of scams are not good because they mostly prey on low-income people.

The way they do that is pretty simple. The sender is implied to be wealthy — or at least outgoing, sociable, and fun — which helps draw the mark into a whole world of fake characters and fraudulent events. There are charity galas, steak dinners, and high-end business travel.

There are charity galas, steak dinners, and high-end business travel

But Read notes that just the opposite is likely true, as the scammers are most likely to be “an abused and captive worker operating multiple phones and attempting to con several people from a compound operated by shady gambling rings somewhere in Southeast Asia.”

That’s certainly a bummer, but if I had to choose, I’d take these oddly literary text messages over any appeal to renew my car’s extended warranty. (And they are definitely preferable to those spam texts from your own phone number, like The Verge’s Chris Welch reported on.)

If you’re not like me and you’d prefer your phone to be spam-free, the Better Business Bureau recommends you take three actions to prevent them: ignore the messages; block the numbers; and never give your personal information to strangers. The Verge also published a detailed guide on how to avoid these types of messages altogether. All of it seems pretty obvious, but then again, this is America, where a TikTok video about “normalized scams” went so viral that people are begging it to stop.

These wrong message texts do seem to gesture at a growing desperation among the scammers of the world. They’re running out of gullible boomers to defraud, so their tactics are getting more sophisticated — or at least less annoying. I, for one, can’t really seem to muster up too much outrage about it. It seems like a small price to pay in order to carry all the world’s knowledge in your pocket.