March Mindfulness is a Mashable series that explores the intersection of meditation practice and technology. Because even in the time of coronavirus, March doesn’t have to be madness.

The messenger matters. That’s the basic proposition of MasterClass, the six-year-old online service that delivers slimmed-down courses of instruction from top names in a variety of fields. Samuel Jackson or Helen Mirren are bound to make you pay more attention than the average acting instructor; the allure of Alicia Keys teaching songwriting or Steph Curry on basketball is obvious. The celebrity talks directly to camera, to you, for around five hours. You walk away feeling inspired, touched by greatness.

How much you can actually learn about their complex craft in such a short space of time is another question. This is why I have a love-hate relationship with MasterClass, which recently changed its business model so your only option is to pay $180 for a year’s subscription. I reviewed the Neil Gaiman and Margaret Atwood writing classes positively, but noted they were more like extended TED talks than condensed college courses. Too often, with its fast-growing roster of celebrities, MasterClass feels a mile wide and an inch deep.

Luckily, that is not the case with one of its latest instructors, Jon Kabat-Zinn, who teaches mindfulness and meditation in a new-for-2021 course. You may not be able to play in the NBA or write award-winning novels after five hours of a MasterClass, but you can get a thorough grounding in the principle and practice of mindful awareness. It’s not hyperbolic to say this MasterClass could change your life. And compared to the cost of, say, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, which covers much of the same ground at a hundred bucks an hour minimum, $180 starts to look pretty cheap.

Here’s the thing: The messenger really matters when it comes to mindfulness. So much suspicion and distrust exists around the concept that it takes a special voice to cut through. Some dopey or aloof New Age-y yoga teacher type might do more harm than good (as they often do in guided meditation apps, in my experience). Kabat-Zinn, who trained in medicine at MIT, is avowedly not that. He has been placing mindfulness in a western scientific context since 1979, when he founded an 8-week course called Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. Now there are more than a thousand certified MBSR teachers practicing around the world, and dozens of studies confirming its effectiveness.

Anyone who has listened to an audiobook of Kabat-Zinn’s bestsellers (like Full Catastrophe Living) knows how delightful his voice is. It retains the accent of his childhood in Washington Heights, the richly diverse northern tip of Manhattan memorialized by Lin-Manuel Miranda in In the Heights. “I was very much a tough New York street kid,” Kabat-Zinn says in the crib sheet PDF that accompanies the class. Except now he’s a super-smart street kid who sounds like he’s smiling all the time. It’s infectious in a good way, the best kind of doctorly bedside manner.

He’s the mindfulness world’s answer to Dr. Anthony Fauci.

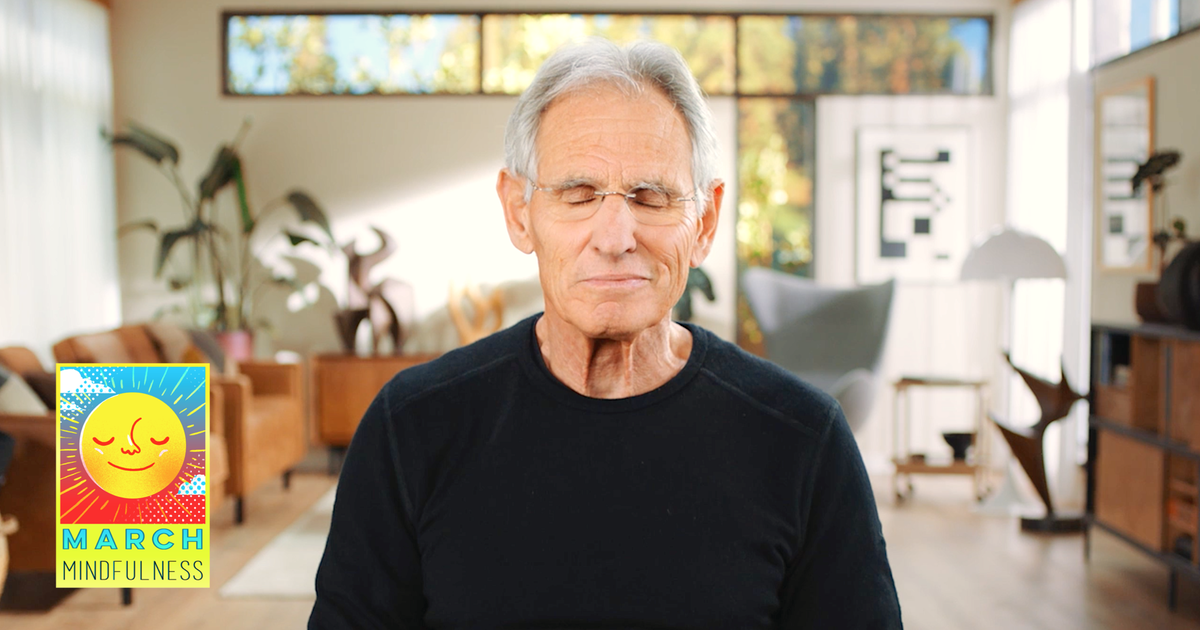

I had no idea what Kabat-Zinn looked like until I started the MasterClass. Turns out he’s the mindfulness world’s answer to Dr. Anthony Fauci, another elder New Yorker who grew up in Brooklyn at the same time. Kabat-Zinn’s face is so craggy it’s fascinating (which is good, because you’ll have plenty of opportunity to focus on it over the unusually long 6-and-a-half-hour MasterClass). In another lifetime it could have been the face of the world’s crabbiest neighbor telling you to get off his lawn. In this one, sharp eyes twinkle and dance under hard-worn wrinkles, and a toothy grin is never far from his face. We should all look this fundamentally at peace with the universe at 76.

Kabat-Zinn doesn’t just play the wise grandpa on TV. He’s a genuinely fascinating contradiction, a meeting of many worlds. His parents were an artist and a scientist. He was inspired by Buddhism but strongly believes its insights are universally applicable, and has worked hard to prove their value within western medicine. You will rarely hear him use the B-word in this course; it’s all about the everyday. “You don’t have a snowball’s chance in hell of becoming the Dalai Lama,” he says in a typical turn of phrase, “but you do have a snowball’s chance in hell of becoming you.”

If this all sounds like something you could show to your parents to help them chill out and become more self-aware, that’s exactly what I was thinking throughout. There are simple tricks literally anyone can try, like meditating for just a few minutes before you get out of bed every day — a process he calls “falling awake,” an effort to “tune the instrument” of the body and mind before you use it. Master that, and you’ll find yourself “falling awake” more often when your mind wanders during the day.

There’s also an effortless, no-bullshit, no-condescension demolition of every point of mindfulness skepticism. Worried that all this non-striving, this focus on the present moment, will make you lose your edge? Nonsense. “If Michael Jordan and LeBron James and Steph Curry practice mindfulness,” says Kabat-Zinn, “then maybe we should rethink this whole question… it doesn’t mean you become a passive person who never gets anything done.”

Indeed, you can get things done faster and better if you’ve taken steps to de-stress your brain first. Do all your work in the present moment, and you’ll never be distracted by anxious thoughts of the deadline.

[embedded content]

None of this kind of I-speak-fluent-sports accessibility means that Kabat-Zinn dumbs down the science. We get a whole segment explaining neuroplasticity, and the MRI studies that show his mindfulness patients are literally growing a calmer alternative to the default mode network — the egotistical chatterbox that’s always reminding you of stuff in the past and future — in their brains. Nor does the science overwhelm. Mostly, it ticks along in the background, keeping Kabat-Zinn from making grandiose claims.

Mindfulness won’t cure stress, he says, because stress is a part of life, but it will put you in a “wiser relationship” with your stress. We shouldn’t try to calm the naturally chattering mind when we meditate, and we definitely shouldn’t beat ourselves up for losing focus. Just noticing what the default mode network is doing — labeling its output as mere thoughts, separate from you — is enough to help grow an alternative.

Most importantly for confused beginners, which it seems we all are when it comes to this ineffable topic, Kabat-Zinn keeps returning to his working definition of mindfulness: “the awareness that arises from paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgmentally.” Meditation is an important forum to practice that. But meditation is not the goal. The real practice is “life itself” — being fully aware of what’s going on in as many of our present moments as possible, accepting the funhouse hall of mirrors in our mind when we can’t.

This is where the MasterClass shines. So few explanations of mindfulness explain why it’s so damn useful. “Awareness really has not gotten anywhere near the kind of attention and investigation that it deserves,” Kabat-Zinn says. “It’s one of our human superpowers. It’s much more powerful than thought.” Employing that superpower, you can start to make different choices. You can slowly change the habits that don’t work for you. Quieting the ego’s voice, you become more yourself, accept your imperfections, and maybe don’t trip yourself up so much.

Did my chattering mind come up with a lot of ways in which this MasterClass is imperfect? Of course it did. These things are so slickly produced that their settings kind of ring false. We’re supposed to feel like we’re meeting Kabat-Zinn at home, but we’re not. The room looks like it was ripped from the page of Architectural Digest, like someone was trying to impress the Room Rater Twitter account and seriously overshot. My wife was thoroughly distracted trying to identify a mid-century modern chair. Maybe putting the class in a blank void — or better yet, the full-catastrophe chaos of a real home — would have been more appropriate.

There’s also a brief unfortunate moment where Kabat-Zinn recounts a favorite phrase from a Korean Zen teacher of his. The teacher would sit before his class and repeat the question “what am I?” with the essential, mindful answer: “don’t know.” Which is fine and lovely as a story, except for the fact that Kabat-Zinn…does the voice. (For those five words, at least; the rest of the quoting of his teacher is mercifully imitation-free.) This isn’t a function of age: Kabat-Zinn is extremely mindful of the state of the world, as he proves elsewhere in the class, and should know why a white guy doing an Asian accent is problematic.

There are also rather a lot of guided meditations in the course. Some are helpful, like the “falling awake” one Kabat-Zinn does in corpse pose (there’s also a whole yoga segment); some like many guided meditations become distractions in themselves. They also get progressively longer, and here’s my confession of imperfection: I have not yet found the patience to complete the hour-long (!) “body scan” or the half-hour “loving-kindness” meditation.

Then again, it’s oddly nice that those depths of boredom (meditation is often boring, as Kabat-Zinn attests) remain to be explored. It’s one indication that this particular course is more than an inch deep. Indeed, given the critical success of this one, I’d like to see MasterClass offer more than one meditation course for our $180 annual fee. Perhaps the next one can explain Transcendental Meditation (TM), a mantra-based form popularized by the Maharisihi and his pupils The Beatles. It seems odd that Kabat-Zinn, a Vietnam war-protesting child of the 1960s, doesn’t so much as mention it — even if just to point out the ways that mindfulness is different from TM.

That may be by design, though. By steering clear of comparisons, Kabat-Zinn’s MasterClass is the purest, simplest, most widely-accessible explanation of mindfulness. It is aimed at the head and the heart, and it lands in both places. There seems no doubt you will leave it inspired, touched by greatness. But not Kabat-Zinn’s. Your own.