Big business opportunities are brewing in the cosmos. Morgan Stanley predicts the space economy will grow from €355 billion in 2020 to over €1 trillion by 2030 — and competition for the rewards is fierce.

The USA remains a celestial superpower, while China is emerging as a powerful challenger. Europe has historically lagged behind the world leaders — but is now carving out a promising niche.

Across the continent, countries are converging around a single segment of the market: small satellites in low-Earth orbit (LEO).

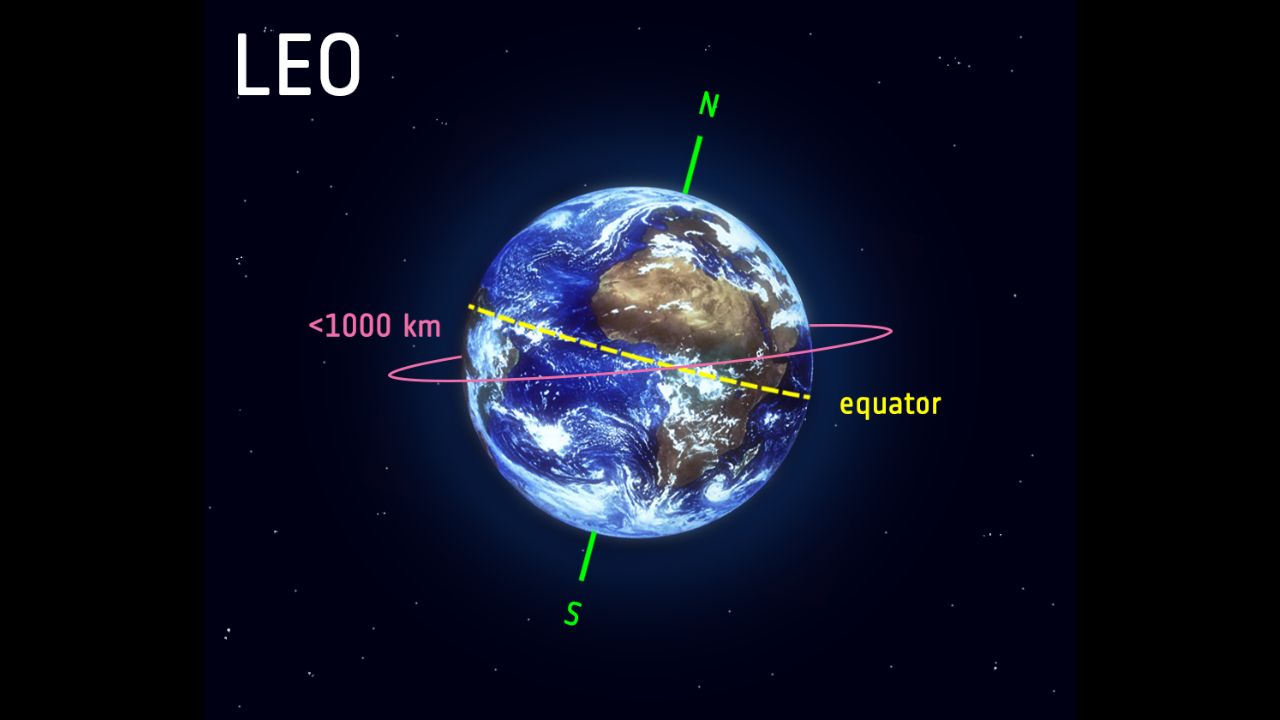

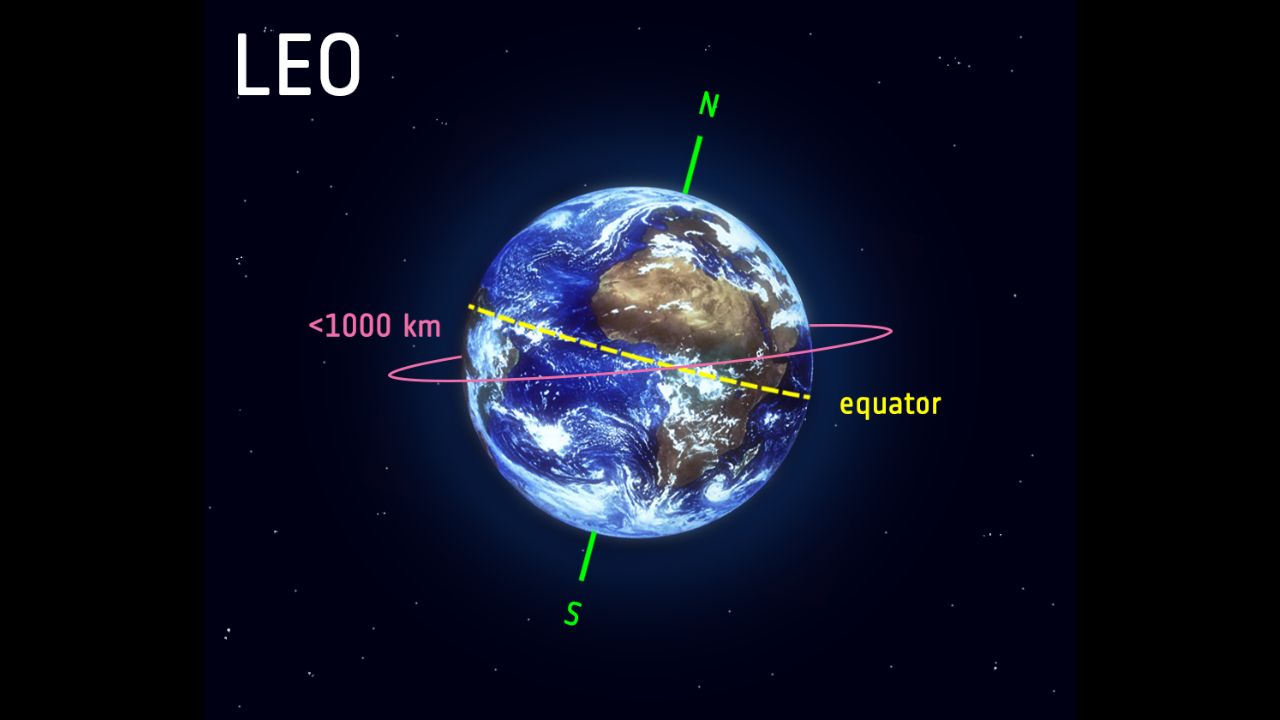

As the name suggests, low-Earth orbits are relatively close to the globe’s surface: a maximum of 2,000km above the planet, and sometimes as low as 160km. Commercial planes, by comparison, rarely fly at altitudes much higher than 14km.

In the 50 years since astronauts last stepped on the Moon, human space exploration has been confined to LEO. Crewless probes still fly deeper into our solar system, but most satellites — as well as the International Space Station — are now found in low-Earth orbit.

The LEO appeal

Small satellites in LEO may lack the glamour of spaceships taking astronauts to the moon, but they offer compelling advantages.

The lower altitude alone has numerous attractions. The costs, risks, and time required for more distant missions have reduced their allure, while the appeal of low-Earth orbit has increased. Among its advantages are speed boosts from gravity’s pull; better signal-to-noise ratios for radar and lidar; higher geospatial position accuracy; expanded launch vehicle options; more convenient journeys and — crucially — fewer resource needs.

‘The pandemic highlighted the need for high-speed connectivity.

Investments have surged as the use cases have expanded. LEO can provide internet connectivity, Earth observation, satellite navigation, and weather forecasting — and it’s becoming more accessible.

As a result, the number of projects in low-Earth Orbit is increasing rapidly. Dan York, who led the Internet Society’s 2022 LEO satellite report, attributes this growth to three key factors: the ceaseless demand for connectivity, the plummeting costs of satellites, and an expanding funding pool.

“The pandemic highlighted the need for high-speed connectivity that can be used for video communication, online learning, e-commerce, and more,” York told TNW. “LEO satellite systems have emerged as a powerful way to provide that high-speed, low-latency connection.”

In the race to commercialise LEO, a single target has been assigned pivotal significance: the first-ever orbital launch from Western Europe.

The territorial advantage

Europe already has a functioning equatorial spaceport — in South America. The Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana, has been in operation since 1968. Originally, it served as the spaceport of France, but it’s now shared with the European Space Agency (ESA), which covers two-thirds of its budget.

Despite being 6,000km from mainland Europe, the site has a propitious location. Its position near the equator reduces the energy required for geostationary orbits, which match the rotation of the Earth. Rockets launching east can harness this momentum, while the centre’s proximity to open sea reduces risks to human habitations.

In Western Europe, however, a satellite has still never been sent into orbit — but the milestone is getting closer.

The achievement would provide more mere than bragging rights. A homegrown spaceport would be a powerful launchpad for a budding LEO sector.

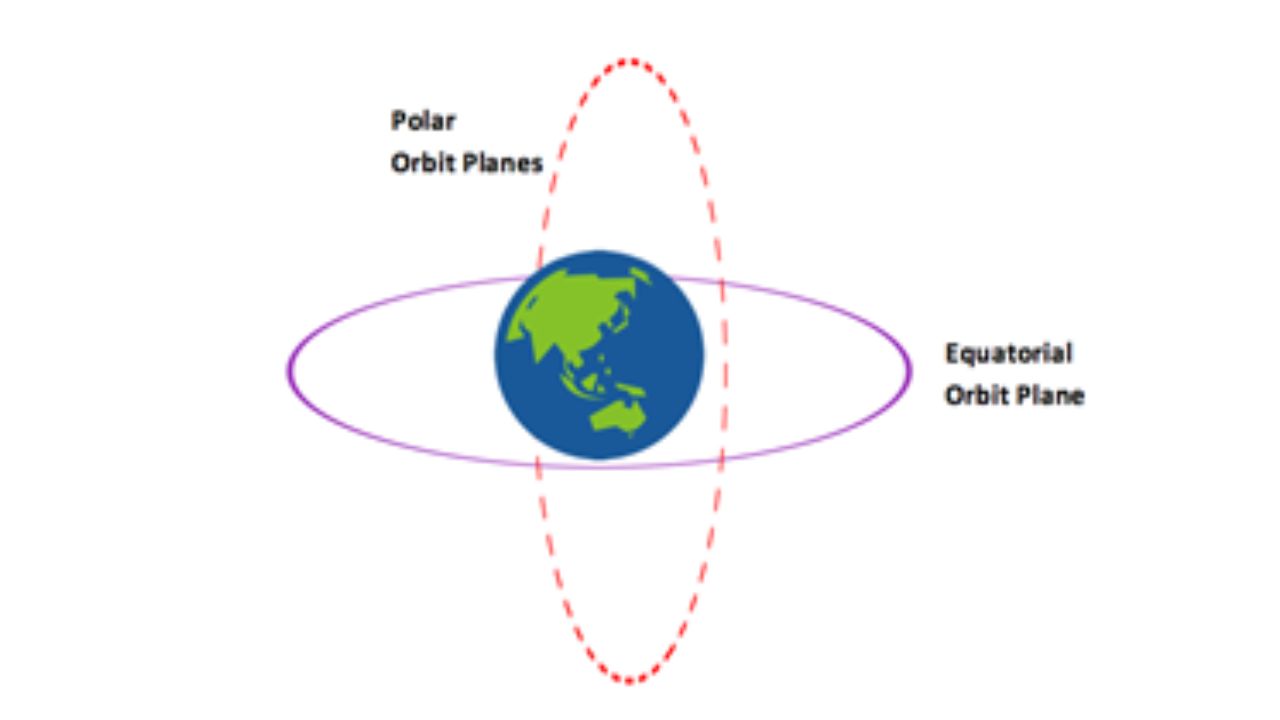

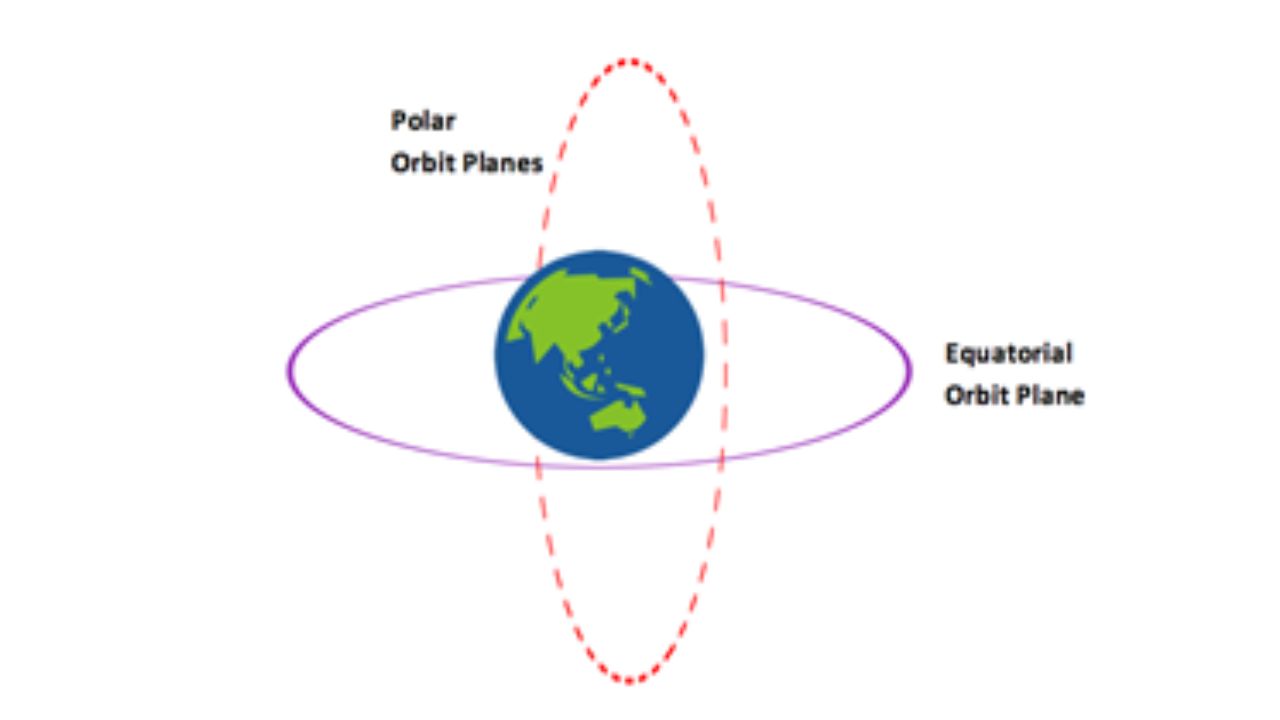

The location also has advantages. Western Europe can harness Earth’s rotation to power polar orbits, a flight path that passes the planet from north to south. This trajectory gives satellites extensive views of the planet rotating below, which is particularly useful for observation, mapping, and surveillance.

Further benefits would arise from the proximity to Europe’s production sites, talent, and connected industries.

“For the first time, the EU will have its own telecommunications constellation.

The war in Ukraine has exposed another lure of LEO. As a result of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s terrestrial internet connection has been disrupted by damage, outages, and jamming. In response, Elon Musk’s SpaceX offered free access to the Starlink satellite internet system, which has kept the country connected.

“The success of SpaceX’s Starlink service throughout Europe, and particularly in Ukraine, has shown the power of LEO satellite systems,” said York.

The EU is now developing its own satellite constellation. Known as IRIS2, the network is designed to maintain internet access during crisis situations. The $6.2 billion project is scheduled to launch by 2027.

“For the first time, the European Union will have its own telecommunications constellation, in particular in low orbits, the new frontier for telecommunication satellites,” said MEP Christophe Grudler, rapporteur on the EU secure connectivity programme.

The bloc has grand plans to compete with Starlink — and that’s just one of Europe’s LEO ambitions.

All around the continent, countries are trying to reap the benefits. The first one to reach orbit will get an edge over the competition.

Contenders in the race

Only nine countries and one international organisation (the aforementioned ESA) currently have orbital launch capability, according to the Pentagon.

Booming demand is expected for their services. The number of operational satellites is projected to grow from 5,000 today to 100,000 by 2040 — and spaceports across Europe are sprouting up to launch them.

Among them is a Spaceport Cornwall in the UK. In January, the site tried to send a satellite into orbit, but the attempt ended in bitter disappointment. After the Virgin Orbit rocket was successfully released, an engine malfunction brought the mission to a premature close.

The failure was a painful setback for Britain’s launch sector, but by no means a fatal one. Virgin Orbit is considering another go in Cornwall, while the SaxaVord spaceport in the Shetland Islands is set to attempt a launch before the end of the year. Further sites are under development in Sutherland, Argyll, Prestwick, Snowdonia, and the Outer Hebrides.

The UK does, however, face growing competition from spaceports in the EU. Most are located in isolated areas of Northern Europe, where populations are sparse and the sea is close.

Sweden’s Spaceport Estrange, for instance, recently became Europe’s first mainland satellite launch facility. The inaugural take-off from the complex is expected in late 2023.

“Europe has its foothold in space and will keep it,” said EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen at the centre’s opening in January.

Another contender in the race is Andøya Space in Norway, which hopes to launch its first satellite rocket this year. Sites in Iceland, the Azores, Andalusia, the Canary Islands, and the North Sea are also in the running.

“This is exactly the infrastructure we need, not only to continue to innovate but also to explore the final frontier further.” -Ursula von der Leyen, President of the @EU_Commission

We are so excited about this new spaceport, which has now been inaugurated.#SpaceportEsrange pic.twitter.com/ASoofEtsZR

— SSC – Swedish Space Corporation (@SSCspace) January 13, 2023

“We’re seeing a proliferation of space bases in Europe,” Marie-Anne Clair, head of the Guiana Space Centre, told AFP in December. “The commercial aspect is real: there is also an abundance of micro-satellites which will require missions from micro-launchers.”

An LEO island

A satellite launch provides a springboard for the host nation’s space sector — even if it fails. The UK’s attempt last month, for instance, added impetus to the local industry.

Before malfunctioning, the rocket did reach space, while Spaceport Cornwall became the world’s newest space launch operations centre. The build-up also boosted domestic satellite development and connected an array of talent, businesses, and public sector organisations.

Among them is Open Cosmos, an Oxfordshire-based startup that had a satellite onboard the Virgin Orbit rocket.

“We delivered a satellite in record time,” Open Cosmos CEO Rafel Jordá Siquier told TNW. “It’s sad not to have it in orbit, but we’re ready to come back and rebuild the satellite at an even faster pace if needed.”

Despite the ill-fated launch, Jordá believes that the UK is now a major player in LEO.

“The UK, with its leadership and its growing commitment towards the space sector, now has a seat at the global table in this industry. And it’s very important that we keep our team there and keep developing our capabilities.”

Those capabilities now encompass downstream applications, data and information services, and the upstream satellite and launch capabilities.

According to Jordá, the UK’s small satellite technology is particularly impressive. Alongside startups such as Open Cosmos, the country is home to OneWeb, one of the world’s leading satellite internet players. In January, the company announced that it now had 542 satellites in orbit – more than 80% of the fleet for its first-generation constellation.

“We now have a truly pan-UK capability.

The landscape also encompasses Surrey Satellite Technologies’ world-leading small satellite platforms, alongside first-rate “CubeSat” nanosatellites produced by Open Cosmos, Clyde Space, and Spire.

Another drawing card is a strong supply chain for space hardware and software. British luminaries in this area range from SMEs such as Teledyne, to aerospace giants like Airbus UK and BAE Systems.

Paul Febvre, CTO at Satellite Applications Catapult and a professor at Bradford University’s new space AI centre, said launch sites will complete the package.

“Now that we are establishing small-satellite launch facilities in both Cornwall and Scotland, with new ventures being developed in East Anglia, we have a truly pan-UK capability which creates the conditions for competition and success,” Febvre told TNW.

Until the British sites are operational, Open Cosmos will take off from other nations. But in the near future, Jordá plans further launches from the UK and France.

“The nice thing about the launch landscape at the moment is that it’s very diverse,” he said. “It’s getting very competitive and that means we have multiple partners that we can work with for different types of orbits.”

Space on the mainland

Another nation with eyes on LEO is France, which has the largest national space programme in Europe.

“France’s space startup ecosystem is particularly strong in LEO satellites, and I think we will see a number of winners emerging from there,” Maureen Haverty, VP at Seraphim, a prolific investor in space tech startups, told TNW.

“France is also the most successful country at encouraging US companies to set up in Europe and is the European hub for a number of key players.”

“We will have our own SpaceX.

A further asset for France is Arianespace, Europe’s leading satellite space launch company. The aerospace giant is currently developing a new reusable rocket, called Maïa, to challenge SpaceX. The launcher is due to be operational by 2026.

“For the first time Europe… will have access to a reusable launcher,” said French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire last year. “In other words, we will have our SpaceX, we will have our Falcon 9.”

Critics have dismissed the prospect of Maïa competing with SpaceX, but the rocket would at least offer a European alternative. PLD Space in Spain plans to provide another.

The company aims to produce Spain’s first rocket to reach orbit — as well as Europe’s first reusable launch vehicle.

Named Miura 1, the 12.5-meter tall vehicle has a payload capacity of 100kg — just a fraction of the SpaceX Falcon 9’s 25,000kg and the Rocket Lab Electron’s 200–300kg. But PLD Space is confident it can serve the booming demand for small payload launches to LEO.

“We have demonstrated that PLD Space is the most promising company to improve European competitiveness in the microlaunchers race to space,” Ezequiel Sánchez, the company’s executive president, said after a successful test last year.

“This fact makes our project strategic not only for Spain but with a European perspective and a reference to show the profitability of reinforcing investment in new players.”

The public investment in Arianespace provides an edge over rivals that rely on private funding — but the competition is growing.

✅Ensayo de misión de vuelo completado con éxito

Ahora sí, #MIURA1 está listo para volar🚀

—

✅Full Mission Test successfully completed.

Now, #MIURA1 is ready to fly 🚀 #VAMOSMIURA1 pic.twitter.com/sOCLbppnQd— PLD Space (@PLD_Space) September 15, 2022

Smaller startups are also fighting for a spot in low-Earth orbit. Haverty, who oversees Seraphim’s investments in LEO satellite businesses, has seen success from those that tap into domestic expertise.

As an example, she points to Seraphim portfolio company ICEYE, which applies Finland’s strengths in hardware and avionics to world-leading synthetic aperture radar. In Lombardy, meanwhile, D-Orbit has harnessed Italy’s space heritage to establish the planet’s only commercial in-space delivery orbital tug company. The firm recently launched its seventh and eighth missions on SpaceX’s transporter mission.

“Overall, I think Europe’s route to success lies in focusing on where they can be world leaders rather than trying to develop a European alternative to an American solution,” said Haverty.

Points of differentiation could also compensate for some shortcomings.

Rejuvenating the old world

The barriers to LEO are lowering, but they remain daunting. Funding in Europe still can’t compete with what’s in the US; space projects are susceptible to delays that can push customers to bigger competitors; nascent markets are tricky to target with commercially viable products.

Startups providing satellite internet services face further obstacles. The established leaders of SpaceX and OneWeb already have LEO constellations in space, customer equipment available, and regulatory approvals in many countries.

“The single biggest challenge for these [European] projects is to get all the components launched and in orbit,” said York, who led the Internet Society’s recent LEO report. “The second biggest challenge is to obtain the regulatory approvals in every country in which they want to operate.”

The growing demand for sparse skills is also difficult to meet. Rewards on offer in the US are often far more lucrative, and the finance and gaming sectors suck up much of the top tech talent.

“We need to encourage and stimulate the understanding in our new generation of engineers, innovators, and entrepreneurs that space is a fantastic place to develop a career and business opportunities, and universities are the knowledge engine for the future economy,” said Febvre, CTO at Satellite Applications Catapult.

Further problems have emerged in Europe’s commercial launch sector. As well as lacking spaceports, the continent is short on effective rockets. Arianespace’s Vega launcher has been marred by repeated failures, the Araine-5 rocket will soon be retired, and its replacement may not be available for over a year.

The rocket shortage could delay the launch of satellites into LEO. Consequently, Europe has become reliant on commercial launch partners, particularly SpaceX.

“Europe does not have the ‘SpaceX Mafia’ effect.

Haverty adds two further weaknesses compared to the US: a limited product focus in satellite projects and a scarcity of second-generation spacetech founders.

“Europe does not have the ‘SpaceX Mafia’ effect,” she said. “European governments focus more on grants rather than on contracts, which makes it harder to grow startups into big businesses.”

The growing popularity of LEO has created another problem. There’s only so much space in space – and it’s starting to get crowded.

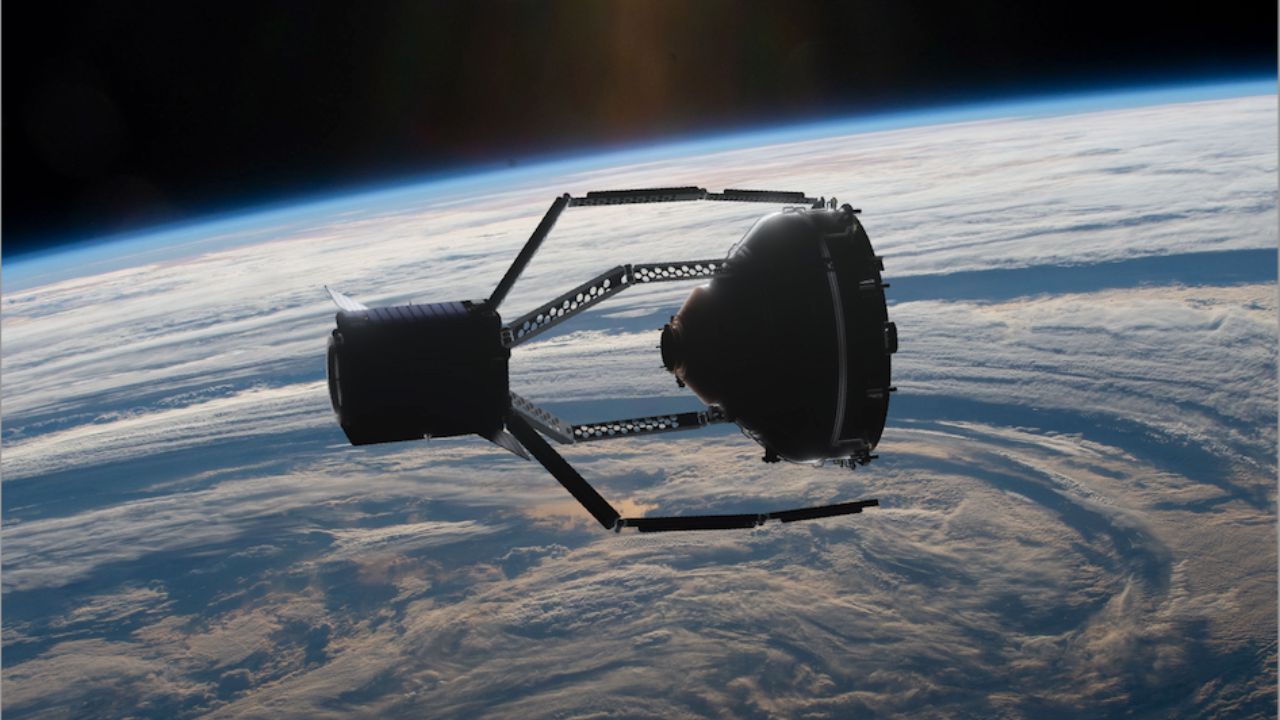

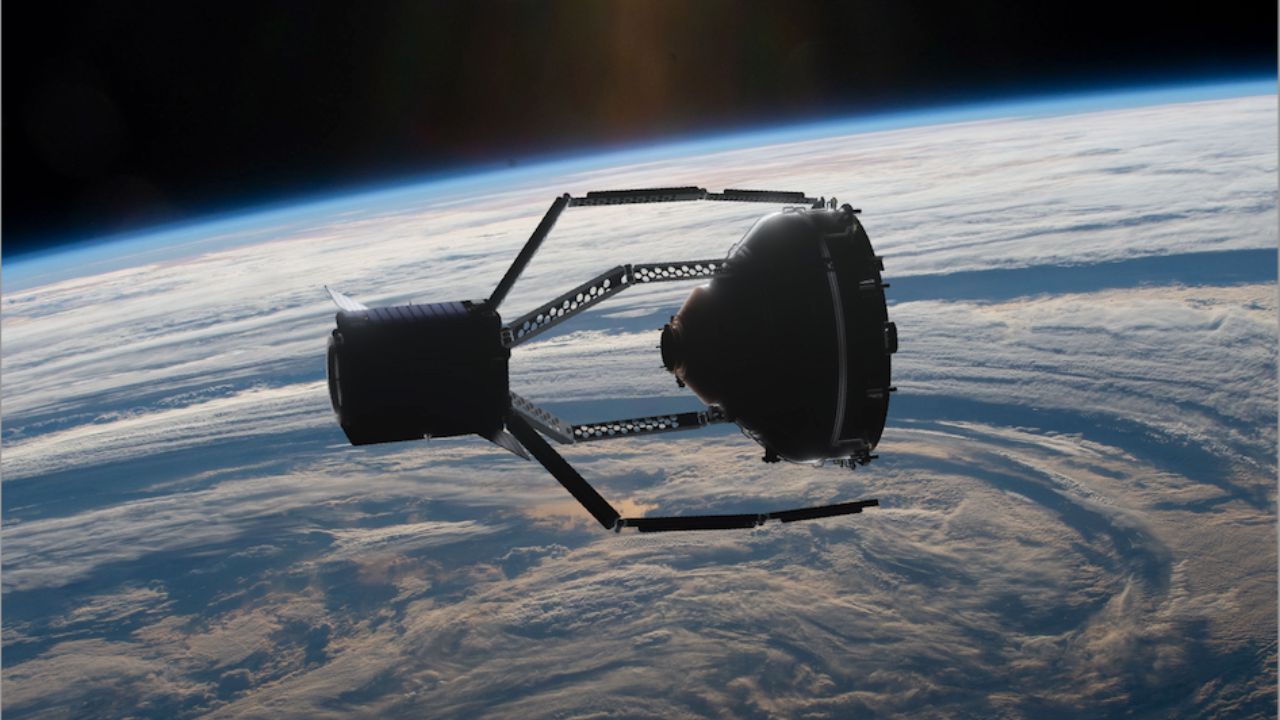

The ESA estimates that there are 36,500 chunks of space debris larger than 10cm, and 130 million between 1mm and 1cm. As these numbers grow, so do the risks of crashes and light pollution.

These threats can also scupper business plans. Regulators consider environmental concerns before deciding whether to allow a satellite launch, but their rules can place heavy burdens on LEO startups. Haverty hopes regulators exert greater pressure on the major operators than their smaller challengers.

“It’s important to remember that the vast majority of debris and causes of potential collisions are caused by the deliberate destruction of satellites by China and Russia,” she said. “Most operators are doing their best to keep space clean.”

On the plus side, the problems of space debris and pollution are presenting business opportunities for space robotics, manufacturing, and in-space servicing. European startups have pitched a range of solutions, from AI monitoring of debris to towing satellites out of LEO.

Cleaning up is one of many emerging opportunities in LEO — and Europe is well-poised to grab a share

Despite the challenges, the continent has an enviable array of major satellite operators, affordable engineering talent, a rich history of multinational efforts, and a superlative satellite supply chain.

Insiders hope the spaceport race will further stimulate the sector. The first country across the line may not end up as the best, but the competition can be a boon for all contenders.

The capital flooding into LEO suggests the prospects are strong. Across the continent, investors are betting that a rising tide will lift all spaceships.

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews