When Mike Fitz first arrived at the remote Brooks River in Katmai National Park and Preserve, home to the now internet-famous fat bears, he spied the telltale signs of a bear-dominated world. It was May 2007. The last of breaths of the Alaskan winter still chilled the air. Leaves hadn’t yet budded. The land was tame. Yet on the cabins, where rangers lived and visitors stayed, he saw claw marks and munched wood.

“It was one of those warning signs that you better pay attention, because they’re coming,” said Fitz, who spent about a decade as a parker ranger in Katmai, and now follows the bears as a naturalist for explore.org, the organization that livestreams the bear cams.

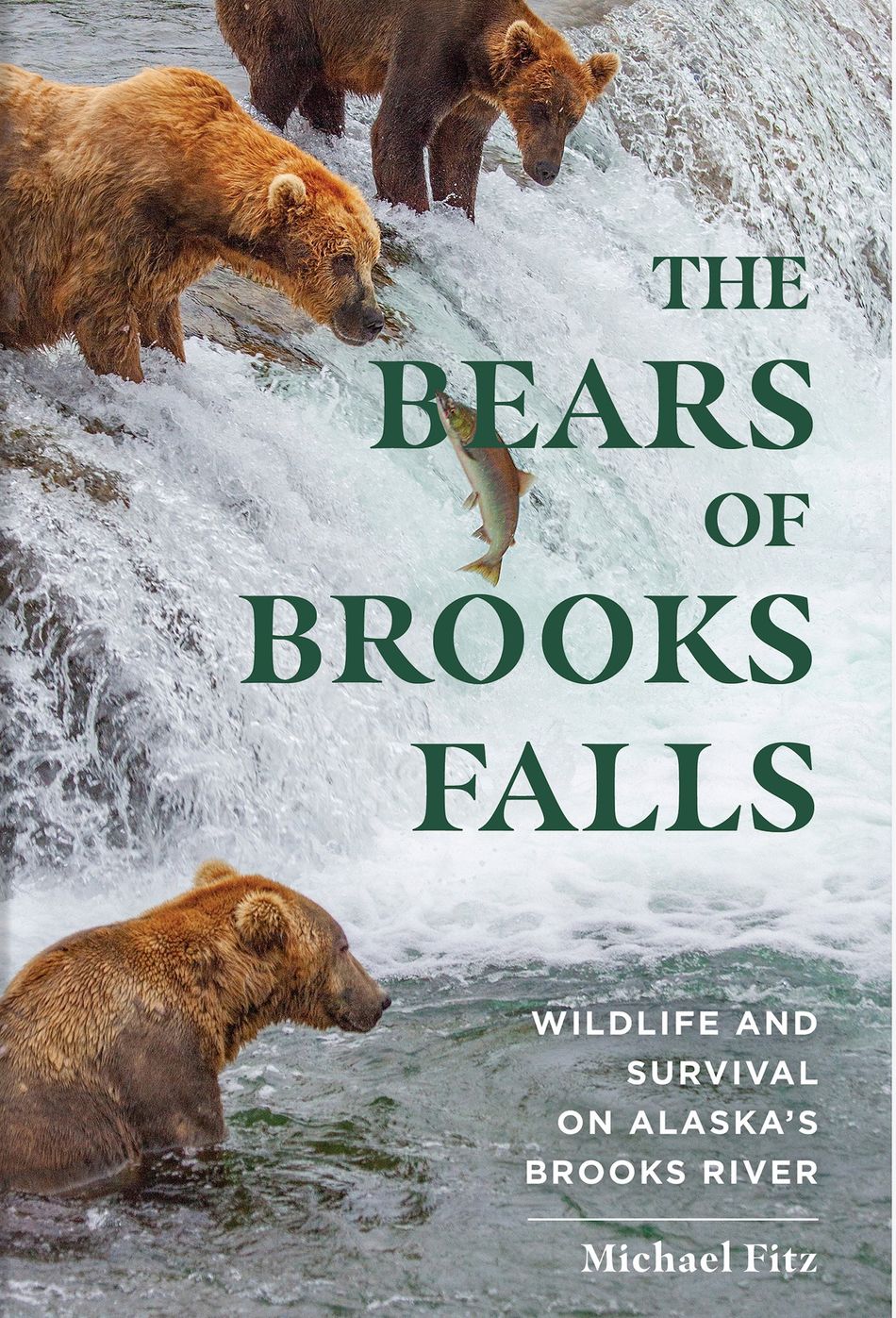

By restlessly watching the brown bears now for a decade and a half, Fitz has earned a mastery of this lively river on the Alaskan Peninsula, where each summer the bears come to devour the skin, red flesh, and brains of plentiful salmon. Often, the bears grow tremendously fat. Fitz has just written a new book about this wild world, The Bears of Brooks Falls, wherein he shows how these animals thrive in a daunting environment, and why the Brooks River region ought to be protected from ever-imposing human activity.

Brooks River, for all of its internet charm, is not a wilderness fairy tale. It can be brutal. Bears fight, bears die, but bears also surprise and succeed. It’s a largely untrammeled wilderness rarely found, if at all, in the Lower 48.

“They’re doing their thing. They’re being wild,” said Fitz. “If they’re there, then there’s a little bit right with the world.”

Fitz spoke with Mashable about the fat bears and his new book, released on March 9, 2021 and published by Countryman Press. The 288-page book is available online through a variety of retailers like Bookshop, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and beyond. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

“The Bears of Brooks Falls” by Mike Fitz.

Image: Countryman Press / W.W. Norton

What’s it like watching the bears return to the river each summer, after their long winter hibernation in Katmai’s hills and woods?

Fitz: Brooks River sometimes has 50, 75, or over 100 independent bears in one year. When you see these familiar faces return, it’s comforting. They’re surviving in an unforgiving landscape. They have to survive on their wits. It’s comforting to see them come back.

Bear 402 teaching her cubs to fish atop the Brooks Falls.

Image: NPS / N. Boak

What do you think about all the eager interest in the livestreamed bear cams?

Fitz: The bear cams have been one of the best things to happen to the Brooks River. The cams offer a very ethical way to visit. Brooks River could never sustain numbers of people like the cams do. [Editor’s note: In the summer and early fall, thousands of people watch the Katmai bears daily, whereas some 12,000 to 14,000 people visit the river in person each year.] The bear cams just provide access to this amazing place. People experience a lot of barriers to visiting parks, and it costs a lot of money to get there. It’s not like driving down the street to your local park.

In your book, what’s a unique place you take readers into the fat bear world?

Fitz: I take a deep dive into the lives of bears themselves. They’re characters in their own right. What does reproduction mean for bear 856, the most dominant bear on the river? How does Otis or Lefty or Holly experience hunger as they try to eat a year’s worth of food in six months? There’s an opportunity to tell the stories of these individual bears that reveal things about bear biology, bear survival, and bear evolution.

Male bears fighting in the Brooks River.

Image: Nps / R. Jensen

Just how wild is Katmai?

[Editor’s note: Katmai was home to the largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century, filling a valley (now called The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes) with volcanic ash that steamed, majestically and unusually, for over half a decade.]

Fitz: Before the 1912 eruption, there really weren’t many eyes focused on this part of Alaska. It was very remote. It wasn’t difficult to escape notice. When Novarupta exploded, it attracted the attention of scientists. They discovered these places that were still steaming. It was really the catalyst that promoted the protection of Katmai in 1918. And it remains wild. Brooks River is perhaps the most iconic wildlife viewing site in all the national parks.

What threatens Katmai’s fat bears?

Fitz: The high numbers of bears we see in coastal Alaska, especially Katmai, need lots of salmon to survive as they do. But ocean conditions are changing. A lot of CO2 is being absorbed by the ocean, and that’s acidifying the water. If we’re not protecting marine conditions for salmon to survive, the Brooks River scene could collapse.

Then there’s the park itself. Each year, more people are spending time around the Brooks River. Are we going to let that continue to grow, largely to the detriment of wildlife, or are we going to try and live within our means? We need to give the bears the space they need to survive.

Sockeye salmon swimming in Lake Brooks.

Image: nps

Will you watch Katmai’s fat bears for the rest of your life?

Fitz: Some summers I may step away from the Brooks River and the bear cams. I’ve always wanted to hike the Appalachian Trail, and haven’t done that. But I want to watch the younger bears growing into mature adults. They were once vulnerable offspring. I look forward to watching the bear hierarchy change over time.