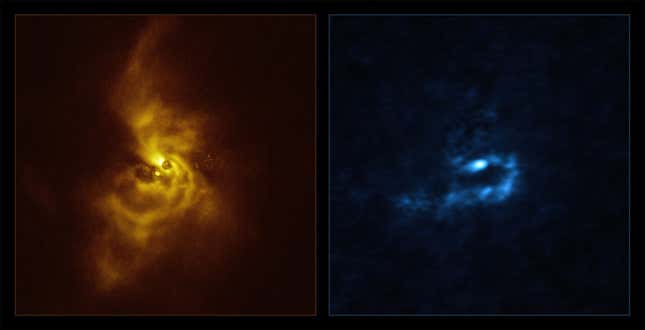

Researchers think they’ve gotten a glimpse at how gas giants like Jupiter form, thanks to a remarkable image of a distant star system.

At the heart of the system is V960 Mon, a young star about 5,000 light-years away, in the constellation Monoceros. The star brightened to about 20 times its normal levels in 2014, allowing a research team using the European Southern Observatory’s Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet Research instrument, or SPHERE, to image it. The team’s research characterizing their findings was published today in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Advertisement

“Our group has been searching for signs of how planets form for over ten years, and we couldn’t be more thrilled about this incredible discovery,” said Sebastián Pérez, an astronomer at the University of Santiago, in an ESO release.

The SPHERE observations showed that the material surrounding V960 Mon was amassing in spiral arms stretching farther than the size of our own solar system.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Follow-up observations of the distant star system were made with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), which penetrated deeper into the dusty material surrounding the star.

“With ALMA, it became apparent that the spiral arms are undergoing fragmentation, resulting in the formation of clumps with masses akin to those of planets,” said Alice Zurlo, a researcher at the Universidad Diego Portales and co-author of the paper, in the same release.

The imagery lends credence to one theory of how gas giants form: from the glomming together of material surrounding a star, a formation method known as gravitational instability. Gravitational instability posits that clumps of material contract and collapse, forming gassy planets. That differs from the more common theory for gas giant formation, called core accretion, in which grains of dust slowly come together to form these large worlds.

Advertisement

Observatories like the Webb Space Telescope can ogle distant gassy exoplanets for clues as to how they formed, but the V960 system offers an intimate glimpse at a possible setting for their formation.

The researchers hope to better understand the chemical composition of the clumps around such star systems, which will in turn inform them what kind of planets might form from the clumps.

Advertisement

As always, more observations of the V960 system and those like it will improve astronomers’ understanding of how planets like those in our own solar system form. The ESO’s Very Large Telescope is set to be succeeded by the Extremely Large Telescope in 2027.

The Extremely Large Telescope will be the largest visible and infrared light telescope in the world and will focus its science on exoplanets, black holes, galactic evolution, and the universe’s earliest days.

Advertisement

More: These Telescopes Will Change the Way We See Space

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews