Jordan Mechner can’t stop looking backward — and that’s not entirely by choice.

The Prince of Persia creator has found himself at the center of an accidental renaissance in the past year thanks to three separate projects lining up at once, some of which he had no hand in. First came Digital Eclipse’s The Making of Karateka, a playable documentary about Mechner’s first hit Apple II game that paved the way for Prince of Persia. That project was followed by Ubisoft’s Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown this January, a new installment to the series that pays homage to Mechner’s original 2D games. That past-facing stretch now caps off with Replay: Memoir of an Uprooted Family, a new graphic novel by Mechner that looks back on both his career and family history.

Through that stretch, the 59-year-old Mechner has had a lot of time to reflect not just on his highs but his lows. The road to each one of his crowning achievements was paved with canceled projects that never saw the light of day. When I sat down with Mechner at this year’s Game Developers Conference to unpack this reflective moment of his long career, there wasn’t a hint of resentment in his voice as he revealed details on his two canceled Prince of Persia games. Instead, he sees both his successes and failures as being of equal importance. The former couldn’t exist without the latter, even if he didn’t always know that in the moment.

“We don’t always realize in the moment that we’re doing something how it’s going to be important or what value it’s going to have,” Mechner tells Digital Trends. “Often we can be surprised in a powerful way to realize how things ripple into the future.”

Deathbouce and Karateka

When I meet Mechner in person for the first time, I feel like I already know him. I’d seen the inner workings of his brain months ago when I played The Making of Karateka, an interactive documentary that includes several interviews with Mechner about creating his first masterpiece. The man I’d meet at GDC would match the one I saw quietly recalling details about Karateka’s creation from a piano bench alongside his father. He’s reserved and precise, carefully organizing his thoughts before answering questions.

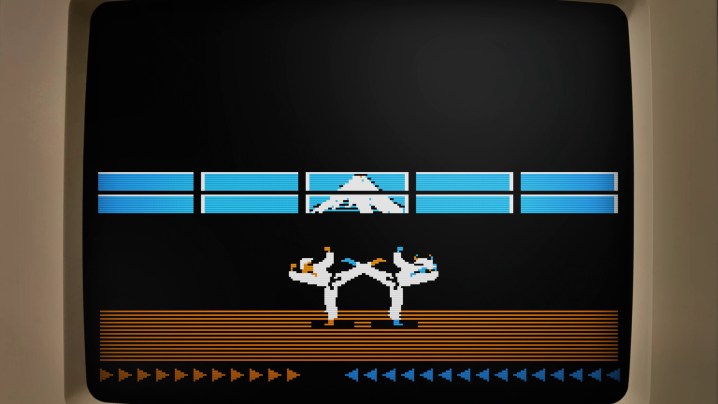

That attitude shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone who’s experienced The Making of Karateka. Digital Eclipse’s detailed documentary paints a picture of a young Mechner agonizing over every detail of his Apple II game. His process was painstaking, so much so that he used rotoscoping to hand-draw his pixelated characters based on real footage he’d shot. It’s a vital historical document for artists that shows a master at work on a singular vision.

I actually programmed that?

Mechner himself wasn’t directly involved in the project’s development. Rather, he sat in for some interviews and allowed Digital Eclipse to comb through his archives to dig up everything from old journals to forgotten prototypes. Mechner, who praises the project, admits that even he was surprised by what the studio was able to dig up.

“There were screenshots and sketches that I hadn’t seen in 40 years,” Mechner says. “They found a prototype for a game with a little rotating planet Earth. I actually programmed that? I must have spent a weekend doing that. I don’t remember ever prototyping that game. I thought it was just an idea!”

While The Making of Karateka largely focuses on the highly influential Karateka itself, a PC game that set the stage for cinematic storytelling in games, it isn’t the only project featured in the collection. It begins with Mechner’s first true failure, a game called Deathbounce that he’d abandon after several failed revision rounds with its potential publisher. It’s in discussing Deathbounce that a unifying wisdom emerges that comes up several times through our conversation.

“Part of the value in remembering and preserving the past is what it gives us in terms of negotiating the present,” Mechner says. “Digital Eclipse’s The Making of Karateka is interesting to game historians, but I think it’s valuable to young developers operating in a completely different world with different technology and challenges. It can be very helpful to experience vicariously what someone else went through. I think part of the value of seeing how much effort went into Deathbounce and taking feedback for it to ultimately not be published can be reassuring for someone who might be beating themselves up about going down a wrong path. It’s just part of the creative process.”

Princess of Persia

What struck me about The Making of Karateka when I first played it wasn’t so much the games featured in it. Rather, it’s how Digital Eclipse tells a tangible story about the ways feedback and criticism can shape art. Throughout the project, players get to try out early prototypes of both Deathbounce and Karateka. In between those versions, Digital Eclipse weaves in letters Mechner revealed from prospective publishers suggesting changes. With each new prototype, I can physically feel the games improve based on Mechner’s willingness to take those notes. Mechner notes that this process has always been fundamental to his success.

“With Prince of Persia, for the longest time, I was determined that this would be a non-violent game,” Mechner says. “It would be about escaping traps and avoiding death, but the player would never fight. My friend Tomi kept telling me that this game needs combat. I resisted. My excuse was that there wasn’t enough memory on the Apple II to add another character — which there wasn’t! But the solution of creating Shadow Man using the same shapes as the player was so magical and transformed the game that I realized Tomi had been right all along. Without that, Prince of Persia wouldn’t have been what it was and we probably wouldn’t be having this conversation today.”

Prince of Persia is a large topic of our discussion thanks in no small part to the series’ latest entry, Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown. Mechner didn’t work on the critically acclaimed release, but it pays homage to his original games with a return to 2D platforming. As we discuss his feelings on the project (he’s a big fan of it), he once again outlines how it wouldn’t have been possible without one of his projects falling apart.

“I moved to Montpellier eight years ago to make a Prince of Persia game,” Mechner says. “That game won’t see the light of day, but there’s a link between that canceled Prince of Persia project and The Lost Crown. Both were made in Montpellier; The Lost Crown was born out of the ashes of that project. The Lost Crown team is wonderfully talented, and having worked with them on other projects, I know their passion for Prince of Persia. I was very happy to see that many of the things we discussed and researched for unannounced projects made its way into The Lost Crown.”

It was going to be called Princess of Persia.

While Mechner discusses the canceled Prince of Persia projects in Replay, he tells me a bit about both titles that were in the works at Ubisoft prior to 2019. One of those would have been a return to form for Mechner, closing a story that he’d been working on since 1989.

“There were two projects,” Mechner says. “One was a AAA open-world Prince of Persia game. The second project was a 2D sequel, the third episode in the original 2D Prince of Persia trilogy. It was going to be called Princess of Persia. Back in 1993, when I did Prince of Persia 2: The Shadow and the Flame, I imagined that as the middle episode of a trilogy. The idea was going to be to complete that trilogy today with a small, simple 2D game. But instead of that, we have The Lost Crown, which is wonderful! I think the story has a happy ending.”

“The things that don’t pay off in the way that we originally think are nonetheless important and do pay off long-term.”

Replaying the past

After parting ways with Ubisoft in 2019, Mechner’s career took somewhat of a left turn. He’d reignite his childhood love for graphic novels, moving from the churn of a massive video game machine to a more intimate kind of art. He’s published several graphic novels since 2019, including books like Monte Cristo and Liberty. Though it might seem like a surprising change, Mechner’s current passion brings his career full circle back to where it was when he was creating small games on his own.

“Writing and drawing every page of a 320-page graphic novel, if it’s like anything, is like coding and doing the graphics for an Apple II game,” Mechner says. “On the one hand, it’s a multi-year project where you need to manage your time. It’s a marathon, not a sprint. But day to day, the craft of drawing one panel or the expression of one gesture is not unlike the challenge of coding a particular subroutine to be as efficient as possible. In that sense, it’s a return to that rhythm.”

The things that are the most painful and the hardest to deal with contain the seeds of opportunity.

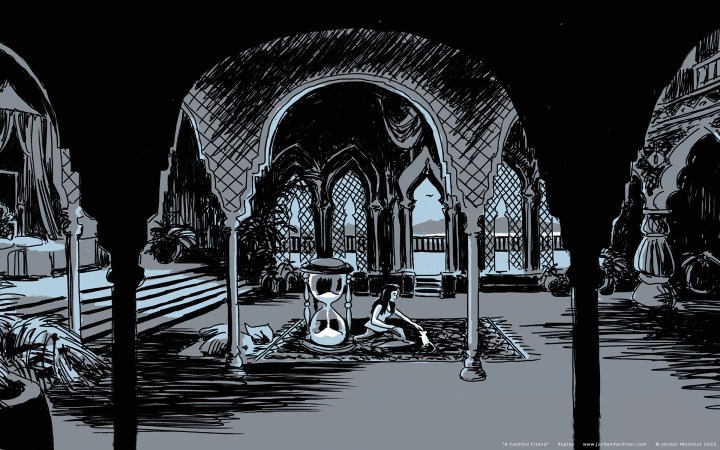

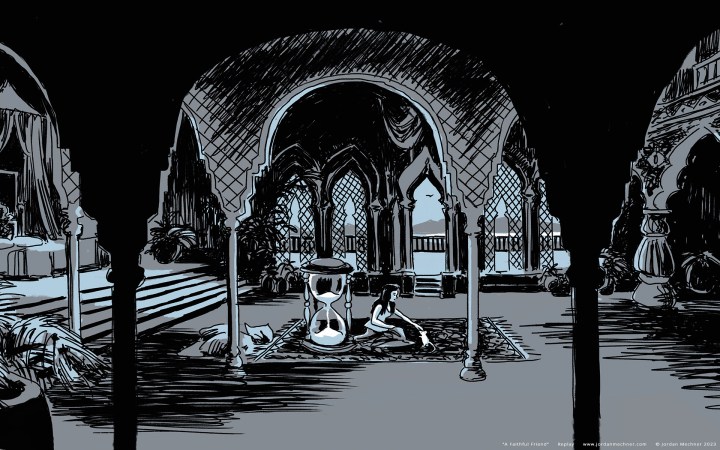

His latest project, an English translation of his 2023 graphic novel Replay: Memoir of an Uprooted Family, is his most personal work yet. The autobiographical book tells an intergenerational story about both Mechner’s career and his family’s history. It chronicles stories from World War I and a rising Nazi occupation in the late 1930s that pushed his grandfather on a journey through France. Mechner connects the dots between those stories and his tale of uprooting his own life in 2015 to move to France and work on Prince of Persia. Mechner didn’t just write the graphic novel; he illustrated it himself.

Again, the running theme rises once again. Whether it aligned with projects like The Making of Karateka by accident or not, Replay almost acts as a final word on Mechner’s current era of self-reflection. It’s a book about looking back on the past and accepting that it’s not something to be changed. We need to accept the past and appreciate the way that even hardships shape the future.

“The subject of Replay is this desire that we all have to somehow turn back the clock and do it again, but do it better. To fix the thing that doesn’t work,” Mechner says. “It’s just the human condition that you can’t do that; the things that are the most painful and the hardest to deal with contain the seeds of opportunity. That’s life.”

I get the sense that Mechner truly believes that philosophy by the end of our conversation. His most passionate moment doesn’t come when talking about Prince of Persia or even Replay, but The Last Express. That project was Mechner’s ambitious 1997 adventure game set aboard a train, one that was deemed a commercial failure. Mechner holds that project in high regard, just as he does his canceled Prince of Persia games. In that sense, there’s no real line differentiating success and failure; Mechner is living proof of that.

“The things that have meant the most to me in my career – and that includes The Last Express, Prince of Persia, and Replay — are projects where I’ve done what I’ve believed in with a group of people who were excited about it too,” Mechner says. “We went with our passion and our vision and surmounted the obstacles because we believed in them. If you can do that, sometimes magic happens.”

Editors’ Recommendations

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews