A new AI study has identified many more potential host species for new coronaviruses than are currently known.

Scientists from the University of Liverpool used machine learning to predict which mammals could be sources for new strains of the virus.

They detected a number of species implicated in previous outbreaks, including horseshoe bats, and pangolins — as well as some new candidates.

[Read: How Polestar is using blockchain to increase transparency]

The study also predicted that hedgehogs, rabbits, and domestic cats could host SARS-CoV-2, as well as numerous other coronaviruses:

Our results demonstrate the large underappreciation of the potential scale of novel coronavirus generation in wild and domesticated animals.

Finding the sources

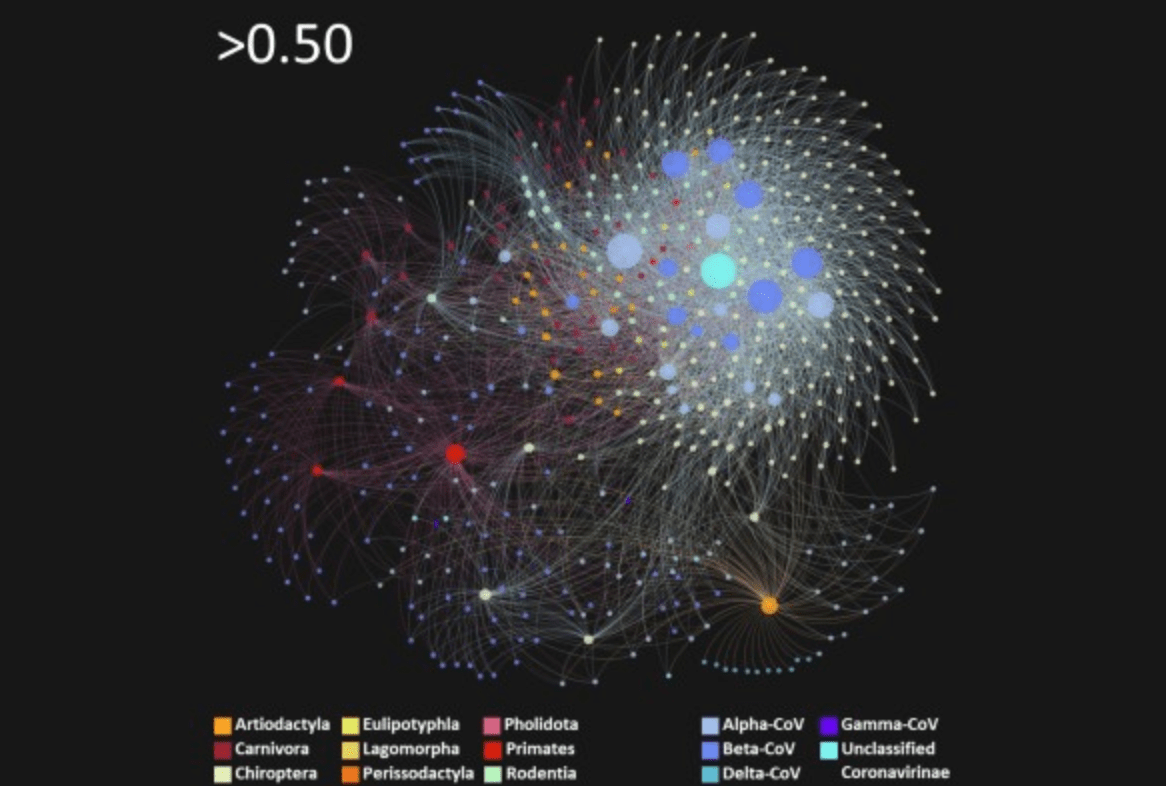

The researchers used machine learning to predict the relations between 411 coronavirus strains and 876 potential mammal host species.

This helped them identify animals that were most likely to be co-infected with different strains of the virus — which could cause a new one to emerge.

The researchers found at least 11 times more associations between mammal species and coronavirus strains than were previously known.

They also estimate that there are over 40 times more species that can be infected with four or more coronaviruses than have been observed to date.

“Given that coronaviruses frequently undergo recombination when they co-infect a host, and that SARS-CoV-2 is highly infectious to humans, the most immediate threat to public health is recombination of other coronaviruses with SARS-CoV-2,” said study co-lead Dr Marcus Blagrove.

The research suggests there could be 30 times more host species for SARS-CoV-2 recombination than are currently recognized. They include the dromedary camel, African green monkey, and the lesser Asiatic yellow bat.

The researchers note that their results draw on limited data and that there are study biases for certain species. Nonetheless, they believe the findings could help reduce the risk of new coronaviruses spreading to people.

Armed with this knowledge, we may be able to reduce the chance of emergence into human populations, such as by the strict monitoring and enforced separation of the identified hosts, in live animal markets, farms, and other close-quarters environments; or we may be able to develop potential mitigations in advance.

You can read the full study paper in Nature Communications.

Published February 16, 2021 — 19:05 UTC