On March 11, 2021, Christie’s, the 255-year-old auction house, made international news with the $69 million sale of a non-fungible token (NFT). The transaction dwarfed previous head-turning blockchain-art sales, and rode a wave of coverage debating the merits and environmental costs of this relatively new art form.

But what, exactly, did the pseudonymous Christie’s bidder MetaKovan actually buy?

The artwork the NFT represents, Beeple’s “Everydays: The First 500 Days,” exists first and foremost in the digital space, and is freely available for everyone to see online. Christie’s even tweeted a picture of it. So it’s not the artwork itself or, at least, not only the artwork that was purchased.

No, the reality of the Beeple NFT is something else.

We asked the company who minted the $69-million NFT in question to explain what’s going on here. We also spoke with a former smart contract auditor and artist exploring NFTs in an effort to get to the bottom of what, on the surface, seems like a relatively straightforward question:

What are you really buying when you buy an NFT?

The answer is both simpler and much more complicated than you might imagine.

It’s all in the metadata

When people talk about owning an NFT, they often describe it in terms of owning an original painting. Sure, the argument goes, there might be millions of copies of that painting hanging in dorm rooms around the world. But if you own the associated NFT, then you own the original piece digitally signed by the creator.

This is, in fact, the argument made by MakersPlace — the company which both minted and published Beeple’s record-setting NFT, and, like Rarible and Foundation, serves as a form of digital gallery as well as NFT shop.

“There are hundreds of thousands of prints and reproductions of the Mona Lisa, but since they are not the original 1/1 Mona Lisa created by Da Vinci himself they are far less valued,” MakersPlace CEO Dannie Chu said over email. “The same principles are applied to NFTs, you can copy and paste an image but only the original, digitally signed by the artist, holds value.”

Beeple’s “Everydays: The First 500 Days” NFT is the most recent, and perhaps most notable, example of this idea in practice.

“The buyer of this artwork is purchasing an ‘NFT’ (non-fungible token) which contains the high resolution digital artwork file itself, as well as an indelible signature of the artist and all transactions associated with the artwork — basically digital proof of authenticity and uniqueness,” Chu said.

In other words, MetaKovan got a bunch of metadata in addition to the art. The former, it turns out, may be where the real value lies.

According to Lee Azzarello, a former Ethereum smart contract security auditor and artist looking into NFTs, that’s partially because the NFTs themselves, in many cases, don’t actually contain the art in question — i.e., the original or a copy. The item represented by the NFT — whether that be a painting, GIF, song, or book — may not always be encoded into the Ethereum blockchain itself.

Often, those items live somewhere else entirely.

“What [an NFT purchaser is] becoming the owner of is a smart contract on the Ethereum blockchain that has some metadata in it,” he explained. “And that metadata points to the name of the work, a longer description of that work, and what’s called the [Uniform Resource Identifier].”

The ERC-721 Non-Fungible Token Standard, which describes in technical terms how NFTs work, notes that the URI in question “may point to a JSON file,” a format which stores and transports data.

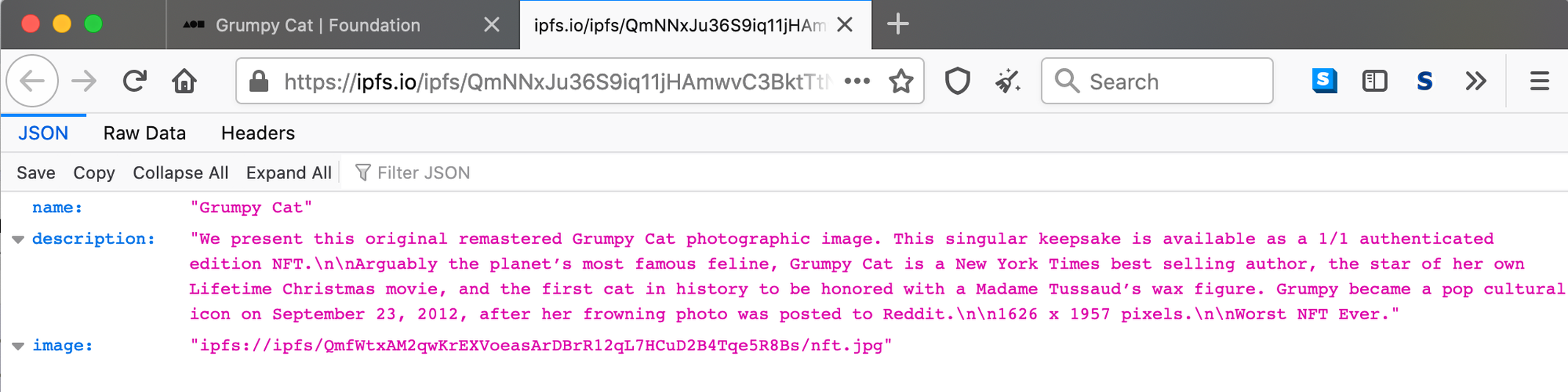

On March 10, Foundation minted a Grumpy Cat NFT. Two days later, that NFT of the famed image of a grumpy cat sold for 44.20 ether — worth around $77,000 at the time.

Here’s what that tens of thousands of dollars of metadata looks like in practice.

Image: screenshot / foundation

Or, to put it another way, Azzarello said most NFTs are “like directions to the museum.”

So where, to continue the analogy, is the museum that typically holds the “original” art in question? In the case of many NFTs, as well as with Beeple’s “Everydays: The First 500 Days,” the museum is somewhere in the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS). This is a protocol which allows for “immutable, permanent links in transactions — time stamping and securing content without having to put the data itself on-chain.”

In other words, it’s a way to link files to blockchain transactions without having to put those files on the blockchain itself.

Chu explained that this safeguards the investment. So even if down the line MakersPlace stops paying its bills or goes out of business, that doesn’t mean the end for the NFTs it minted.

“Because the artwork is hosted on a decentralized file system (IPFS), the artwork is hosted by multiple computers and users around the world, including MakersPlace,” Chu said. “If MakersPlace no longer exists, as long as there is another online host to serve this file, the file will continue to live on.”

OK, so…

That brings us back to the original question:

What is an NFT?

Technical aspects aside, Azzarello said that, essentially, “it is a transaction among a number of parties to agree on ownership.”

And that ownership is of metadata which points to a file — often in the form of a URI. And that file is the art associated with the NFT.

Which leaves us with another question:

Are NFTs dumb?

“I don’t think it’s any more dumb than a business like Christie’s,” Azzarello said. “I think it is using a techno-utopian vision to take a business like Christie’s and put the financialization of that business onto a blockchain.”

And what of the environmental costs of NFTs? As far as Azzarello’s concerned, critics are “being pretty hyperbolic about how the art market will singlehandedly melt the planet.”

He pointed to a blog post by the artist Sterling Crispin titled “NFTs and Crypto Art: The Sky is not Falling.” Crispin (who, it should be noted, makes NFTs) argues, in part, that “Attention is a finite resource, and outrage is a type of attention. We should focus our efforts where it actually matters.” In Crispin’s mind, what actually matters are fossil fuel subsidies, coal power plants, and fracking.

All that aside, MakersPlace believes NFTs provide real value to artists and collectors alike.

SEE ALSO: Deleting your Clubhouse account is a nightmare, especially for sex workers

“This movement offers an opportunity to interact with a novel medium of artwork in a personal, new way; be the sole or one of the few owners of a coveted digital creation; experience tremendous financial gain on the secondary market; and of course, to support and join the next major art movement,” Chu added.

It also offers buyers the opportunity to own their very own chunk of metadata — which, admittedly, can be some pretty important stuff — that’s authenticated by the Ethereum blockchain.

Whether this is an opportunity that those currently sitting on the NFT sidelines will ultimately value is an altogether different question.