People who speak limited English struggled to access telehealth services in the US during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a new analysis, affecting their ability to connect with medical care. It’s something experts worried about as soon as health organizations made the switch from in-person to virtual care.

“That was really a concern of ours — who is getting left out?” says Denise Payán, an assistant professor of health, society, and behavior at the University of California, Irvine, who worked on the study.

Payán and her colleagues interviewed staff and patients at two community health centers in California about their experiences with telehealth between December 2020 and April 2021. One of the clinics serves a primarily Spanish-speaking population, and the second serves a primarily Chinese-speaking population. Neither had offered video or phone visits before the pandemic started. Both started to them available soon after the California stay-at-home orders in March 2020 — first with phone calls, then with video. The researchers spoke with 15 clinic workers and nine patients.

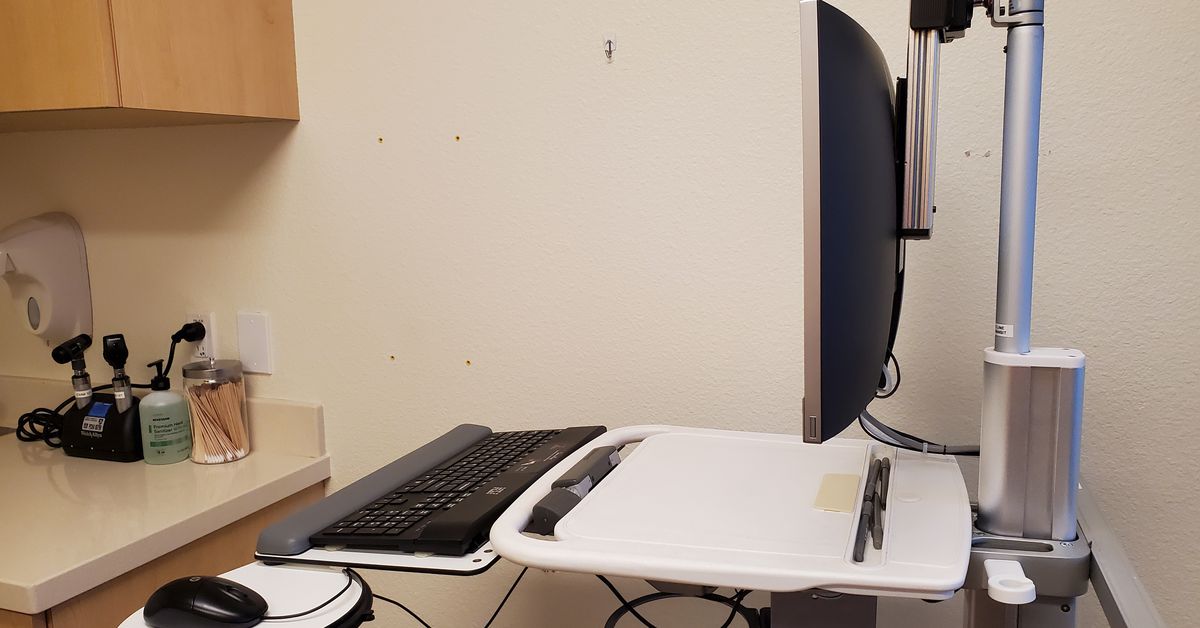

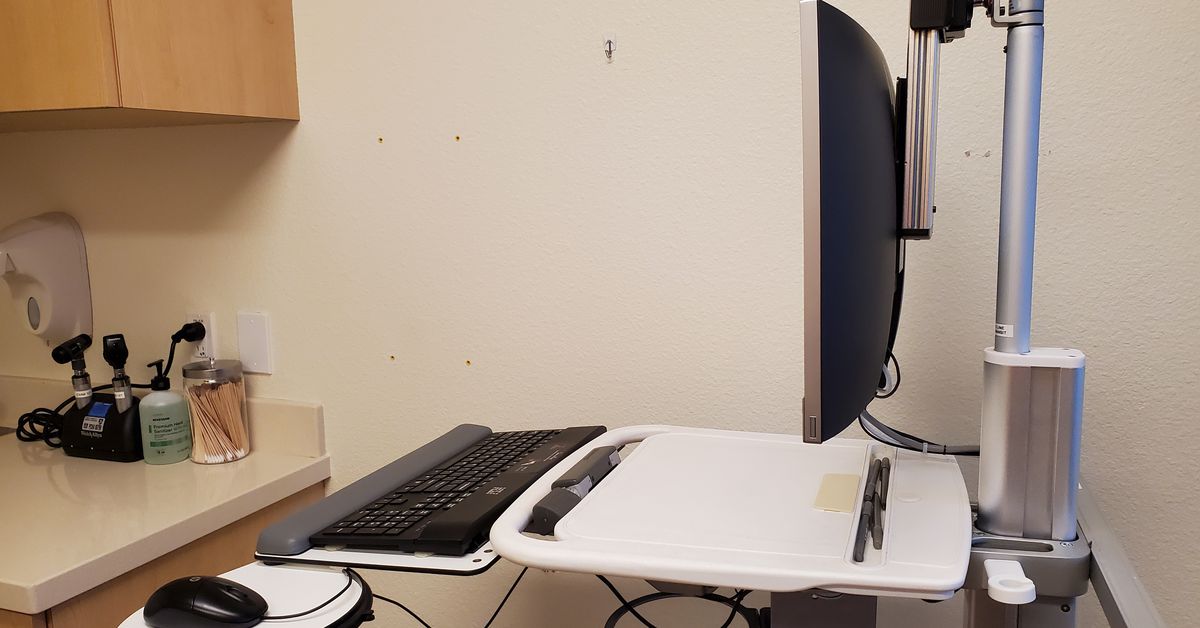

Clinic patients who spoke limited English struggled to set up and use platforms like Zoom for health visits, the researchers found. “Things like not being able to read FAQs,” Payán says. “There’s reliance on either clinic personnel, staff, or family members — like kids, who are helping their parents get connected to video visits.”

“There’s reliance on either clinic personnel, staff or family members”

Even if information on a platform was translated into other languages, it was often translated badly. “Patients said, ‘I went into the FAQs in Spanish, and I have high fluency and a high reading level in Spanish, and it made no sense because it was such a poor translation,’” Payán says.

Integrating third-party interpreters for non-English speaking patients into telehealth platforms was also difficult, Payán says. It’s a logistical challenge to add a third person to a phone or video call, particularly in platforms that aren’t set up to support external interpreting services. That can mean additional delays to care. Even something simple like a patient getting a call from a number they didn’t recognize — and didn’t want to answer — could derail the process. And having those interpretation services are key for good care: people who speak limited English are at risk of bad health outcomes without them because they can’t understand their medical providers as well.

Luckily, at the clinics Payan spoke with, many doctors and clinic staff were bilingual — they were able to talk with patients in their first language. It showed how much recruiting and retaining staff from the same communities as the patients can help build trust and improve care, particularly during challenging times, Payan says. “It is very important that [the doctor] speaks the same language because that way, we understand each other,” one Spanish-speaking patient said in a study interview.

“With that older population, it is a little bit more difficult because they don’t know how to use the technology”

But even without language barriers getting in the way, many patients didn’t have the digital literacy to navigate telemedicine, didn’t have devices that could use the telehealth tools, or didn’t have good enough internet access to connect with a provider. “With that older population, it is a little bit more difficult because they don’t know how to use the technology or they need the assistance of their relatives,” one care coordinator said in a study interview. Unhoused patients were also particularly hard to reach because they didn’t have reliable phone or internet connections.

Phone visits, without a video component, were far more accessible to older patients and patients who spoke limited English. They were great resources for patients and helped connect them with medical care. But they don’t have all the benefits of video calls — like letting a doctor see a patient’s body language or getting a sense of their environment. “Saying, well, we can’t figure out the technology piece, so let’s just do let’s just do audio — I don’t think that’s good enough,” Jorge Rodriguez, a health technology equity researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, told The Verge in 2020.

The findings of the study show how important it is for telehealth platforms to consider their most vulnerable users while developing tools. People who speak languages other than English should be included in pilot tests, for example, Payán says.

“Increasingly, the focus in Silicon Valley is on diversity, equity inclusion, this is clearly it — are you actually meeting the needs of a diverse set of patients?” she says.

Some smaller groups and entrepreneurs in digital health are working to expand internet access and improve digital health tools for vulnerable groups, Payán says. But it’ll take big platforms with high use getting on board to drive major changes. “The onus is on them to really pilot test and prioritize the development of high-quality language services,” she says.