The new 13-inch MacBook Pro hit shelves on May 4th. Kate Kozuch, a journalist, ordered one to replace her old, broken 2015 model. She was confused by the different add-ons and configuration options — “The numbers hurt my brain,” she told The Verge. But after much research, she finally settled on one.

When it came time to check out, however, Kozuch realized she might have to wait much longer than she’d hoped. Apple estimated that her unit would arrive between May 26th and June 2nd. It didn’t take quite that long, but it still took longer than anticipated. Kozuch got her MacBook on May 18th — two weeks after placing the order.

Robin Gloss, a college student, also ordered the new MacBook on May 26th. She hasn’t received it yet, but it’s supposed to come on June 10th. Gloss isn’t thrilled about having to wait that long; she’s worried that her 2015 MacBook Air will crash before it arrives. “It works, but barely,” she said. “It doesn’t have enough processing power to run the WordPress plugin I need.”

“It works, but barely”

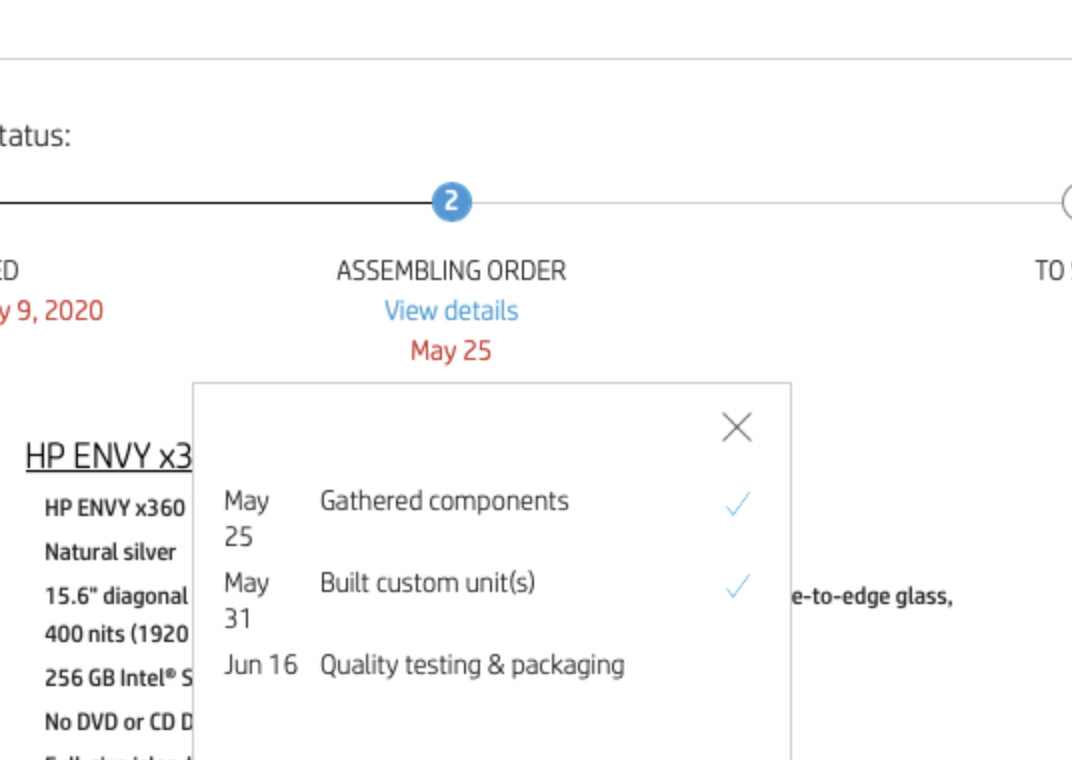

BJ Adams ordered a 15-inch HP Spectre x360 on May 3rd as a desktop replacement. HP said it would ship on May 29th, and arrive on June 4th. On June 1st, Adams asked for an update; the arrival date is now June 23rd.

Adams was so irritated that he considered canceling the order and going to Best Buy. “HP is doing bad,” he complained. “They need to get out of the laptop business.”

If you, like Gloss, Adams, and Kozuch, have shopped for a new laptop in the past few months and been met with multiweek shipping estimates and out-of-stock signs, you are not alone. Retail analytics firm Stackline found that in recent weeks, traffic to laptop product pages has grown 100 to 130 percent (year over year). Conversion rates (that is, the proportion of visitors to laptop product pages who actually purchase), conversely, have plummeted; they’re normally around 3 percent, but in mid-May they hit an all-time low of 1.5 percent. In other words: people are looking for laptops more, but they’re having trouble finding products in stock to actually purchase.

That’s because the COVID-19 pandemic has put two unique pressures on laptop manufacturers: higher demand and lower supply.

Sayon Deb, senior analyst at the Consumer Technology Association, says that outbreaks hit laptop manufacturers the hardest in the first few months of 2020, when cities across China were in lockdown. “Somewhere around the end of February was the last batch of shipments,” Deb said, referring to units coming to the US from Asia. “Around mid-February was when production was spinning down. It ground to a halt.”

It’s hard to say when supply chains will be back at full capacity

China’s lockdowns and quarantines have eased over the past few months — around 75 percent of the country was back at work by the end of March, according to McKinsey. But shortages continued, and even as supply chains ramp up again, it’s hard to say when they’ll be back at full capacity.

That’s partially due to the time it takes to transport laptop parts to manufacturing facilities. OEMs ship some components from outside of China, and those (due to their size) commonly travel by air. Gartner analyst Mikako Kitagawa estimates that around half of that cargo usually comes on commercial flights. The pandemic hasn’t been kind to those modes of transportation; countries around the world have restricted air travel, and airline capacity has crunched. Delta reduced its flights by 40 percent in March due to plummeting demand, while the International Air Transport Association projected that airlines could see between an 11 and 19 percent loss in global passenger revenues through the end of this year.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20016814/Screen_Shot_2020_06_03_at_4.10.51_PM.png)

Then, there’s the matter of getting the assembled laptops across the ocean. Tight port restrictions are a hassle for ocean freight, and the logistics of transporting units from ports to warehouses, stores, and ultimately your home are another battle entirely. Many couriers, including UPS and FedEx, have suspended their service guarantees (which promise you a refund if you don’t get your package), citing COVID-19’s disruptions to supply chains, travel restrictions, and limited flight capacity, and noting that they anticipated delays. Container volume in Shanghai fell by 20 percent year over year this past February, and cargo volume in Los Angeles fell by 23 percent, according to a New York Times report.

Deb expects units that were slated to arrive in the US by mid-April could arrive a month and a half later. “Production is speeding back up, but it takes time for it to get finished, get loaded up, get shipped over,” said Deb.

But experts say the biggest problem is that COVID-19 has brought a spike in demand — one that supply chains, even at full capacity, weren’t set up to service. “You can’t just decide today you’re gonna build one and sell it tomorrow,” Stephen Baker, vice president and industry advisor at the NPD Group, said of laptops. “You don’t plan for sales to go up 40 percent when sales are going down every week by 30 percent.” (PC sales saw a sharp year-over-year decline in Q1, following early lockdowns in China.)

“You can’t just decide today you’re gonna build one and sell it tomorrow”

The surge began in mid-March, when the US first went into lockdown, but it’s still going: during the week ending May 23rd, Windows notebooks and Chromebooks saw a mid-40 percent year-over-year increase in unit sales according to the NPD Group. During the week ending May 2nd, TV, tablet, and PC sales saw a 33 percent year-over-year increase in revenue, and a 38 percent increase in unit sales. “It’s some of the fastest growth rates this category has seen in a long, long time,” said Michael Lagoni, CEO of Stackline.

And, of course, supply constraints make it hard to gauge how much demand there really is. “If there’s a lot of demand that is being unfulfilled because people want something specific and they can’t get it, we can’t really tell that,” said Baker. “When you can’t fulfill everything but you’re still selling 40 percent more than you did last year, you can’t really see that missing piece.” He noted, though, that “as weeks go by and you have that same level of growth, that makes you believe that there’s still a lot more demand left in the marketplace.”

One contributor is the nation’s new fleet of remote workers; Gallup polls from the end of May found that 40 percent of Americans are “always” working from home due to the pandemic, and 22 percent of Americans “sometimes” do. Gartner predicted that 48 percent of employees will work remotely after the pandemic, compared to 30 percent who did so pre-pandemic.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20017005/Screen_Shot_2020_06_03_at_5.27.19_PM.png)

Another is students, over 40 million of whom have been impacted by school closures. This is apparent from the fact that sales of cheaper devices have exploded in recent months. Stackline found that online laptop sales had an average sale price (ASP) of $516 in March, compared to $730 throughout 2019; it’s the lowest ASP Stackline has ever seen, outside of Prime Day and Cyber Monday. Search volume for the phrase “laptops on sale” is higher, too — over 30 times higher than the first few months of 2019. Laptop sales under $700 also grew around twice as fast as the overall category through April and May.

“We think a big driving force behind this is that a lot of students now have to do their schoolwork at home, and many of them didn’t have a laptop at home,” Lagoni said. “So you saw a huge surge in orders for those student-based, lower entry price point models.”

And, of course, with people stuck at home, the desire for a better entertainment experience comes to the forefront. “A lot of people use their computers to watch Netflix or other kinds of streaming services,” Baker said. “If you have an old computer you might not want to watch those things on an old screen with a slow processor. We’re seeing people upgrade to the extent they can on those kinds of features.”

“Consumer confidence has been going down”

Experts think, however, that the surge isn’t likely to last. Though, given the unpredictability of the pandemic, it’s difficult to say how long it will last.

COVID outbreaks may be temporary, but the economic consequences are less so. Gartner forecasted last week that worldwide device shipments will still decline 13.6 percent in 2020, and PC shipments will decline by 10.5 percent — though shipments of laptops, tablets, and Chromebooks will decline a bit more slowly than the PC category.

“Consumer confidence has been going down,” says Kitagawa. “There are huge numbers of unemployment happening, and people feel so uncomfortable about these economic uncertainties. They’re gonna tighten their spending.”

Whether to buy a laptop now depends on how flexible you are and how wed you are to one specific model. “The supply is going to be eased out going forward, so you might have more options later in the year,” says Kitagawa. She guessed that growth might continue through the end of this year, but emphasized that it’s hard to put a specific end date on stock shortages.

If you need a laptop now, your best bet is flexibility; the more models you’re willing to go for, and the more retailers you’re willing to dig through, the more likely it is you can find the configurations and specs you need with reasonable ship times.